KÁLMÁN Anikó és WIN Phyu

Influences on teacher trainers' lifelong learning competencies

Introduction

Lifelong learning should embrace the full range of informal, non-formal, and formal learning and its focus on learning from early childhood through post-retirement (Commission, 2002). Depending on the researchers ' formulation, there are various lifelong learning competencies to measure the lifelong learning process. In 2006, the European Commission launched a wide-ranging consultation process to revise the Recommendation on Essential Competencies for Lifelong Learning (Commission, 2018; European Commission, 2018).

In their studies, a significant finding, starting with the education sector, is that a wide range of terminology and meanings are used despite competency frameworks addressing a similar set of competencies. The intended application, target audience, and geographic location influence its diversity. The major conclusions of the review process were (a) to assist students of all generations in acquiring the key competencies necessary for continuous learning, (b) to modify the benchmark structure to reflect present and emerging demands to guarantee individuals can acquire the necessary competencies and (c) to identify strategies for fostering competency-based education, using lifelong learning approach. Teacher educators and other education personnel all play critical roles in achieving this.

The essential core competencies have become included in the proposal for an updated European guideline structure of critical competencies for lifelong learning:

literacy competence

multilingual competence

mathematical and science competence

digital competence

learning to learn competence

citizenship competence

entrepreneurship competence

cultural awareness and expression competence

Literacy competence is recognizing, comprehending, communicating, producing, and interpreting ideas, sentiments, information, and opinions in oral and written form using visual, aural, and digital media. The native tongue, the official language of a country or region, and the language of communication all contribute to its development. In this scenario, literacy competence can be acquired in various societal and cultural contexts, including education, training, employment, family life, and leisure.

Multilingual competence is the capacity to use a variety of languages successfully and appropriately for communication. Understanding, expressing, and interpreting ideas, concepts, ideas, emotions, information, and perspectives in spoken and written form are the foundations of communication in foreign languages.

Mathematical competence is acquiring and utilizing numerical concepts and reasoning for various issues in real-world contexts. The focus is on methods and activity in addition to information, building on a solid foundation of numeracy. To various extents, the capacity and readiness to apply mathematical forms of thought and presentation are components of mathematical competence. The capacity and inclination to explain the natural world through research and observation, formulate questions, and come to conclusions supported by evidence is referred to as competence in science.

Digital competence refers to the robust, critical, and ethical integration and use of digital technology for professional and social learning. It covers data and information, education, teamwork and communication, media literacy, media creation, online digital creation, safety, and property rights.

Learning to learn competence is the capacity for self-reflection, adequate time and information management, and teamwork in a better direction, maintaining resilience, and managing one's learning. It includes the capacity to deal with complexity and uncertainty, to learn new things, to encourage and preserve one's mental and physical health, to live a health-conscious, future-focused life, to show empathy, and to handle disputes in an inclusive and encouraging environment.

Citizenship competence is the ability to participate fully in civic and social life and engage as responsible. It depends on one's awareness of concepts and systems in the economic, social, legal, and political fields, sustainability, and globalization.

Entrepreneurial competence is the ability to capture opportunities and develop ideas into commodities that benefit others. It is built on the ability to design and manage initiatives that have cultural, social, or economic worth by using originality, rational thought, and problem-solving skills.

Competence in cultural awareness is understanding and respecting the diverse artistic and other cultures so that information is imaginatively conveyed and shared in all the other cultures. It entails being actively involved in comprehending, growing, and communicating one's personal opinions and identity as a member or position in society in various situations and manners.

These key competencies are also defined as a combination of attitudes, knowledge, and skills. Moreover, they are described in terms of sustainability, gender, equal rights and opportunities, acceptance of cultural diversity, innovative thinking, and media literacy. Another point of view is that the first three are specific to a particular domain. Their description, adoption of syllabi, and appraisal seem pretty straightforward. The last five relate to domains of generality or transversality (Steffens, 2015). This reference framework utilizes an extensive range of themes, including critical reflection, innovation, enterprise, conflict, risk analysis, judgment, and therapeutic emotion management in each of the eight primary skills. Practitioners in education and training can use it as a standard guideline. It creates a shared knowledge of the skills that will be necessary in the present and the future. The reference framework outlines practical strategies for fostering competence growth through cutting-edge teaching strategies, testing procedures, and staff assistance (Commission, 2019; European Council, 2006).

Myanmar's GDP is declining due to political instability, with services and industrial sectors suffering the most. The Southeast Asia 2023 Survey Report shows a 47% increase in socioeconomic gaps. Urbanization is increasing, with 89.5% literacy rate (Seah et al., 2023). The European Framework is a vital resource for evaluating the lifelong learning competencies of teacher trainers in Myanmar. International collaboration and sharing of best practices are facilitated by comparing their skill sets to global standards. This information and policy decisions can also shape initiatives for the professional development of trainers in Myanmar. Myanmar may enhance the quality of teacher training programs and education by comprehending these competencies.

Many researchers have addressed how to transform educational institutions to foster lifelong learning among educators, administrators, and students; our previous systematic literature review of lifelong learning helped us gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. The research gaps we identified led us to plan an investigation of the lifelong learning competencies of teacher trainers using a mixed-method research design. In our previous empirical studies (Thwe & Kálmán, 2023a, 2023b), we examined the lifelong learning competencies of teacher trainers and some background factors, but our prior quantitative studies have some limitations, and the findings are still controversial compared to previous studies (For example, Pilli et al., 2017; Sen & Durak, 2022; Shin & Jun, 2019). Therefore, we conducted this qualitative study to explain more factors influencing teacher trainers' lifelong learning competencies. The purpose of preparing this paper was to explore their perceptions of lifelong learning competencies as well as the impacts of learning communities and learning strategies on those competencies.

Literature Review

The factors that can influence lifelong learning competencies can be identified qualitatively, quantitatively, or both. Shin and Jun (2019) identified the faceted effects of both personal and institutional factors on lifelong learning competencies, and Deveci (2019) used a Scale of Interpersonal Communication Predispositions for Lifelong Learning to study present-day interpersonal interactions in the classroom as well as to predict future lifelong learning engagement. Separately, using a lifelong learning scale, Bath and Smith (2009) discovered features and traits that might point to a person's propensity for lifelong learning, and using the responses to a questionnaire on experience with lifelong learning as well as scores from two semesters at the university, Grokholskyi et al.(2020) established the importance of psychological traits and metacognitions for lifelong learning competences. Meanwhile, Adabaş Kaygin and Sahin et al. (2010; 2016) also quantitatively analyzed lifelong learning competencies based on background characteristics and identified the role of personal traits in the capacity for lifelong learning.

Yen et al. (2019) described how personal learning environments can be used to promote never-ending learning, andBuza et al. (2010) explained how education can guarantee high standards and lifelong learning; the latter authors found that their teacher educators had varying ideas about lifelong learning; they focused on acquiring a variety of skills; recognized problems; had strategies for addressing, locating, and using information; and comprehended learning strategies for acquiring and applying new knowledge. In a mixed-methods study, Matsumoto-Royo et al. (2022) demonstrated that assessment can improve metacognition abilities and foster lifelong learning in teacher education. Lavrijsen and Nicaise (2017) highlighted the significance of extrinsic barriers for explaining unfair involvement in lifelong learning using data from the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies. Meanwhile, in a qualitative study, Zuhairi et al. (2020) discussed the challenges in enhancing lifelong learning in open universities and suggested integrating online instructional design and strategies with policies and strategies for school leavers, student portfolios, and services and support for students with special needs.

Muller and Beaten (2013) studied lifelong learners' learning strategies by administering a learning style instrument and a coping strategies scale and found that learning strategies can affect their lifelong learning. Separately, Nacaroglu et al. (2021) found that those with self-regulatory solid learning capacity are more likely to pursue lifelong learning. They recommended that future researchers consider extraneous influences such as post-COVID-19 learning communities and learning strategies. Meanwhile, according to Entürk and Baş (2021), Klug et al. (2014), and Selvi (2010), teacher competencies are also related to lifelong learning competencies. We also considered the potential effects of specific learning strategies for teaching competencies on lifelong learning competencies.

The findings from our previous studies showed that teacher trainers perceive that they demonstrate lifelong learning competencies that are related to their perceptions of lifelong learning and learning strategies, and the student participants' ages influenced these and where their education degree colleges were located. Our findings are consistent with results from other studies in which gender (Pilli et al., 2017; Sen & Durak, 2022; Shin & Jun, 2019), education level (Ayanoglu & Guler, 2021), and years of teaching service (Bozat et al., 2014; Kuzu et al., 2015; Yildiz-Durak et al., 2020) affected lifelong learning competences. In the current study, we measured teacher trainers' lifelong learning competencies based on their background factors; specifically, we measured the teacher trainers for eight main competencies identified as related to lifelong learning.

In those previous studies, the teacher trainers perceived that they were most competent at learning how to learn and the minor competent in math and science; education level and gender had no significant influences on any of the eight lifelong learning competencies. We did find that the region of the interviewee's education degree college had recognizable impacts on the teacher trainer's multilingualism, digital citizenship, entrepreneurship, learning to learn, and cultural awareness competencies. Additionally, age played a critical role in literacy, digital, and citizenship competencies, but only teaching services affected digital competence. Here, we note that additional factors such as socioeconomic status, individual differences, exposure, and training could have also affected teachers' lifelong learning competencies. However, we did not explore any such factors in this study. Instead, based on these previously identified factors, in this study, we investigated the lifelong learning competencies of teacher trainers in Myanmar based on their background factors, learning communities, preexisting teaching competencies, and learning strategies.

Previous researchers have clearly defined and discussed learning communities for professionals (Buysse et al., 2003; Hord, 2004; Thompson et al., 2004; Xiao & Saedah, 2015), and Deveci (2022) reminded researchers to consider the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on such learning communities and competences. The pandemic and the associated societal impacts substantially changed every aspect of teaching and learning, including engendering different learning communities. To date, researchers have not established a definition of a new learning community, which made it necessary to prepare an operational definition for this study. The pandemic restrictions required teachers and students to establish new methods of teaching and learning remotely, a brand-new circumstance; however, many teachers did have access to online training and online communication with other teacher learners during the time they were not actively teaching. Based on the current findings, the operational definition of a new learning community is a place where teachers can teach and learn online, acquire both technological and pedagogical skills, and share new experiences.

In response to our above conclusions, we conducted the current study to resolve the limitations of our previous studies by exploring more possible factors that can influence the lifelong learning competencies of teacher trainers. The following research questions guided our study efforts:

How do teacher trainers understand lifelong learning and lifelong learning competencies?

What are the factors that promote or hinder the lifelong learning competencies of teacher trainers?

How can teacher trainers' learning communities influence their lifelong learning competencies?

Which learning strategies do teacher trainers use to improve their teaching competencies?

How can teacher trainers' teaching competencies relate to their lifelong learning competencies?

Methodology

Research Design and Data Collection Procedure

In this study, we followed our previous quantitative works to conduct a qualitative study that would support or reject the quantitative results (Creswell, 2012) with the aim of understanding the critical factors of teacher trainers' lifelong learning competencies. We prepared a qualitative semistructured interview instrument based on our quantitative study variables and findings and conducted the interviews remotely using the messaging applications Vibe and Messenger; the first author also recorded the audio of each interview. The first author initially wrote the interview questions in English so the co-author could check and revise them. The first author, a native of Burma, then translated them into Burmese. Two PhD candidates who were formerly teacher trainers in Myanmar aided this effort by reviewing the translated version and offering their feedback on the questions' content and clarity. The instrument was modified based on their recommendations. This study adhered to the interview topic guides' methods, questions, and note-taking areas to conduct the interviews (Creswell, 2012). One-on-one interviews are conducted so that participants can freely share ideas without feeling uncomfortable. In addition, each participant gave oral consent, which we recorded before each interview. Following the interviews, we reviewed each transcript and filled in any gaps.

Participants

The participants in the formal study were 12 teacher trainers performing at education degree colleges in Myanmar whom we selected according to purposive sampling based on their background factors including age and region. Table 1 presents the interviewees' profiles, and we note that only one male teacher trainer was willing to participate in this interview.

Table 1. Profile of the interviewees

|

Background factors |

frequency |

% |

|

|

Gender |

male |

1 |

8.33% |

|

female |

11 |

91.67 % |

|

|

Age |

20-30 years |

6 |

50.00% |

|

31-40 years |

5 |

41.67% |

|

|

41-50 years |

1 |

8.33% |

|

|

Region |

Lower |

3 |

25.00% |

|

Upper |

9 |

75.00% |

|

|

Education level |

Bachelor |

1 |

8.33% |

|

Master |

3 |

25.00% |

|

|

Phd (still studying) |

8 |

66.67% |

|

|

Teaching Service |

1-5 years |

5 |

41.67% |

|

6-10 years |

6 |

50.00% |

|

|

11-15 years |

1 |

8.33% |

|

|

Total |

12 |

100% |

|

Instrument

Although we conducted semistructured interviews using a predetermined order of questions as a guide, we asked additional questions when it seemed appropriate to encourage interviewees to explore their perceptions more deeply (Cachia & Millward, 2011). Our leading interview guide consisted of 15 questions covering the teacher trainers' perceptions of lifelong learning and lifelong learning competencies, factors they felt influenced lifelong learning competencies, and the impacts of new learning environments and learning strategies. However, participants were encouraged to elaborate on any of their answers. The interviews followed the protocol below:

Perceptions of lifelong learning and lifelong learning competencies:

How do you understand lifelong learning?

How can you tell if someone is practicing lifelong learning?

According to the European Commission, there are eight key competencies for lifelong learning: literacy, multilingual, math and science, digital, learning to learn, citizenship, entrepreneurship, and cultural awareness. Among these, which are your highest and lowest competencies? Why do you think so?

Factors influencing each competency phase:

Based on your answers, how do you think these highest and lowest competencies are related to your background factors?

What factors could improve your competences?

What factors hinder them?

New learning community phase:

Since COVID-19, how is your learning environment?

Which areas have changed, and which remain the same?

How do you think that these changes or the absence of changes can affect any of your Lifelong learning competences?

Learning Strategies phase:

Which learning strategies do you use to improve your teaching competencies?

Which one do you prefer to use?

By improving them, how can you also improve your lifelong learning competencies? Which competence?

Data Analysis

Before the main study, we conducted a pilot study on these study questions with a group of aforementioned PhD students who did not take part in the study to ensure its validity. With their consent, the first author took notes on their performances while they pretended to be being interrogated. Before the formal interview started, the first author made a few minor wording adjustments for the Burmese translation. We used the six interconnected qualitative data analysis processes to understand the recorded data from formal interviews (Creswell, 2022). For anonymity, we coded each interviewee as TT1, TT2, .... We first transcribed the data to determine whether hand analysis would be appropriate. We then read each full transcript multiple times for more than thirty days to better understand their responses. Next, we used inductive reasoning to code the text data based on drawing meanings and developing themes from the data. Inductive approaches are commonly used in qualitative data analysis, incredibly grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), and provide a simple, straightforward method of deriving conclusions related to evaluation questions (Thomas, 2006).

This technique also helps us use mixed methods to compare our current qualitative and previous quantitative results and draw more insightful conclusions (Grbich, 2022; Vaismoradi & Snelgrove, 2019). Two themes were ultimately chosen for this study after they were labeled and defined. The findings of this study then revealed the themes of perceptions of lifelong learning and lifelong learning competencies as well as the factors influencing them.

Results and Discussion

Understanding of Lifelong Learning and Lifelong Learning Competencies

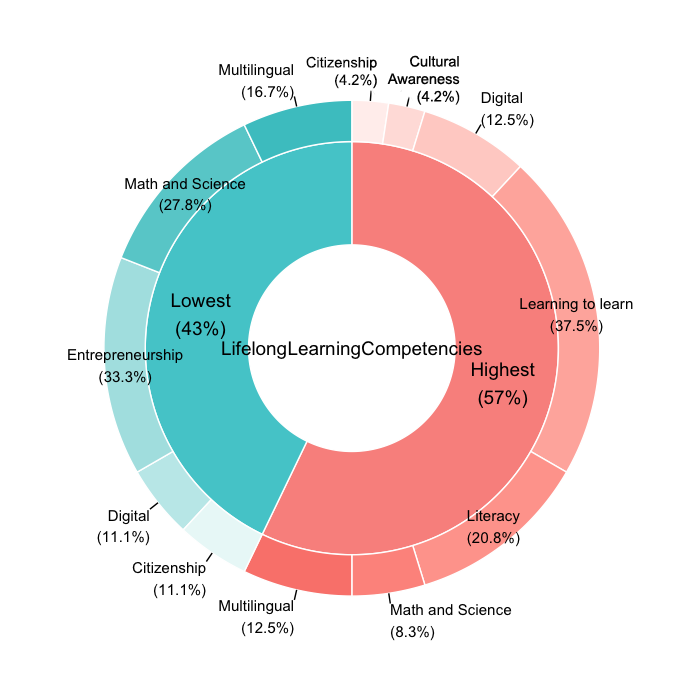

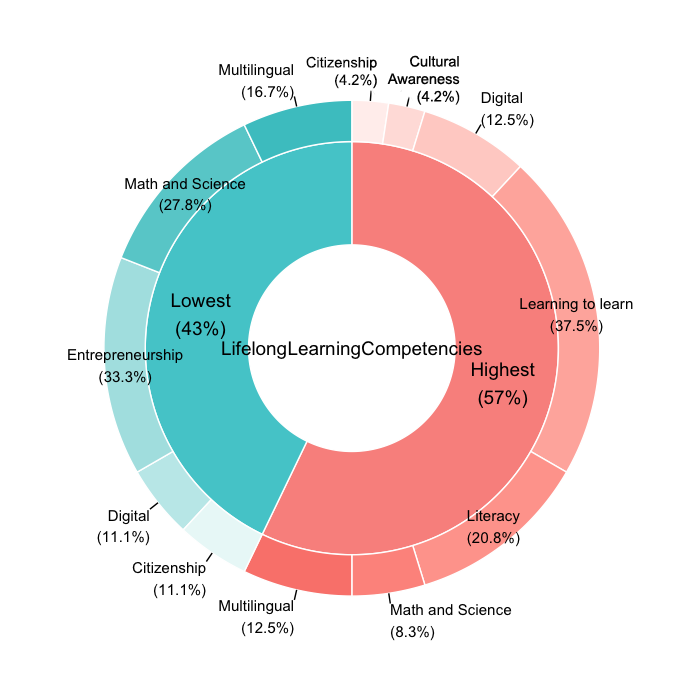

With the first research question, we aimed to explore how teacher trainers perceived lifelong learning and its competencies. According to Table 2, they understood that everything is changing at an incredible rate in modern times and that teaching is not an exception, and they also understood lifelong learning to entail keeping current with contemporary developments. Through reflection, everyone learns consciously and unconsciously throughout their lives and applies what they have learned and where they should apply it. The majority of their perceptions about lifelong learning come from their teaching profession. All teacher trainers view that the lifelong learning of a person can be measured by communicating with them and gauging their professional performance and attitudes. In contrast, only one teacher trainer responded that it is impossible to assess the lifelong learning of a person. It is supposed that they need to recognise that eight key competencies can be used to determine whether or not a person practices lifelong learning. Then, they are explained about eight key competencies and asked to assess themselves which are their highest and lowest competencies. In more detail, Figure 1 graphically displays how the 12 study interviewees perceived their strongest and weakest lifelong learning competencies.

Table 2. Teacher Trainers' Perceptions on Lifelong Learning

|

Teacher trainers |

Lifelong Learning means |

|

TT1 |

Staying up to date with the ever-changing world. |

|

TT2 |

Keeping up with 21st century learning is always necessary as a student and as a teacher of students. |

|

TT3 |

Performing new things in the teaching profession is also a constant learning process, since every teacher is a forever student, not only to gain the degree but also to adopt new teaching methods. |

|

TT4 |

The process of improving oneself through learning. |

|

TT5 |

All of us learn consciously and unconsciously throughout our lives, and by reflecting we apply what can be useful and where it should be applied. |

|

TT6 |

Learning unknown things. |

|

TT7 |

It is true that everyone learns the things they need in their daily lives, but the amount that they learn is different. Everyone is interested in learning new things. |

|

TT8 |

Humans, as well as all living things, are constantly learning for survival. |

|

TT9 |

Learning for the sake of gaining new knowledge. |

|

TT10 |

Gaining knowledge about the profession by learning new things. |

|

TT11 |

Every person learns for the basic needs and professions, social skills, and how to create new things unconsciously and consciously throughout their lives. |

|

TT12 |

Besides formal education, informal learning and non-formal learning are also included. |

Fig. 1. Highest and lowest competences of lifelong learning of teacher trainers

Factors That Promote or Hinder Each of Lifelong Learning Competencies

Teacher trainers' opinions on the reason for their highest and lowest level in their various competencies were continually sought. Most of the teacher trainers reported that gender, age, region of college, education level, and teaching experience had had no effect on their lifelong learning competences. TT1 reported that her competences were only partially associated with her teaching experience and where her education degree college was located, but TT5 and TT7e reported that their lifelong learning competences had been related to their teaching experience; TT5 also stated that the education level might have influenced her lifelong learning competences. TT8 also associated her lifetime learning competences with the region where her college was located, and TT1, TT8, and TT9 agreed that they were meant to just obey directions from those in higher positions in their schools and could not question them; it should be clear that teachers cannot achieve entrepreneurial competence in this manner. TT9 also felt that being a woman and her fear of making a mistake had contributed to her low entrepreneurial competence, and TT10 perceived age as associated with her weak math and science competence.

In addition to the background factors listed above, other factors contributed to determining each competency of lifelong learning competencies. They revealed fostering factors by focusing on their highest competences, which include learning to learn, literacy, multilingual, and digital. TT1 recognized that she was a fast learner, and she learned what she needed to succeed in her job if the skill qualified her for promotion; TT2 was also interested in learning new things related to the profession. TT3 believed her grandfather's teaching her English had made her multilingual, and TT4 perceived himself as a fast learner and a competent digital professional based on his experience at a media and advertising company. TT5 became multilingual by participating in a foreign language course focused on learning English. TT6 asserted that a person who is interested in something familiar is likely to want to learn more about it, and in fact, TT7 enjoyed her job as a teacher trainer despite some challenges; she was consistently learning about the new curriculum, and in this way, she increased her capacity to learn. TT8 considered that practicing and developing habits were related to learning to learn, and TT9 expected that she would become knowledgeable and interested in math because it had been her university's specialized major; TT10 reported being interested in learning a skill if the individuals around her possessed the skill of interest. TT7 and TT11 were very enthusiastic about participating in new curriculum training and learning for personal growth. In the same way as TT1, TT12 reported having learned and applied new knowledge to pursue a promotion.

The teacher trainers also identified factors that limited their competencies, particularly science and math, entrepreneurship, and multilingualism, and they admitted that their limited competence in these areas was attributable to their lack of confidence, interest, awareness, and drive. Some also chose not to put effort into lifelong learning competencies without connection to the teaching profession or applicability to their current positions. TT3 believed that because she was raised in an ordinary household, she lacked any entrepreneurship abilities, and TT8 reported that her lack of entrepreneurial competence was linked to a fear of failing. TT7 also reported being overworked and depressed and reported certain aspects of her health and family history as all having an impact on her capacity for lifelong learning. In a related sentiment, TT9 believed genetics was vital to developing specific competencies.

New Learning Community

All the teacher trainers in this study indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had drastically changed their learning communities, although they revealed considerably different perspectives and experiences, particularly concerning lifelong learning competencies. Most reported that their multilingual and digital competencies had had time to improve after the pandemic. Additionally, while the schools were closed entirely, the teacher trainers had extra time to acquaint themselves with new digital tools and participate in online training. However, TT6 admitted that she had stopped learning English and using the computer once training programs such as the Toward Results in Education and English (TREE) program had ended; instead, she focused on how to teach the new curriculum to her students. TT8 had a different perspective because she had more post-pandemic options for online and offline courses, which increased her learning capacity. TT4 and TT7 reported that their digital competence had already been good and discussed how they would have the chance to apply their skills after the pandemic.

Regarding drawbacks to the new learning communities, TT2 and TT7 discussed how it was impossible to reach an instructor or communicate face-to-face in real-time during asynchronous online classes. Also discussed her experience as a PhD student who studied in China and returned to Myanmar following the pandemic. She felt that because everyone around her was speaking Burmese, her multilingualism decreased, particularly in English and Chinese; despite this, she reported that she was still motivated to continue writing her dissertation in English. Meanwhile, TT 4 talked about his changes. He had been fired from the media and marketing firm following the COVID-19 outbreak and decided to earn a master's degree; subsequently, he joined the academic community. This interviewee found that his learning strategies had changed as the number of lessons decreased during the pandemic, and all interviewees reported generally experiencing new learning communities after the pandemic that had affected their lifelong learning competencies, particularly their digital and multilingual skills. Despite this, they still prefer face-to-face learning.

Learning Strategies and Teaching Competencies

We found in the previous quantitative studies that the strategies the teacher trainers had applied to improve their teacher competencies were associated with their lifelong learning competencies, but we did not show which specific learning strategies they were practicing. In this study, our interview data revealed which learning strategies this group of 12 teacher trainers had used to improve their teaching competencies. Most reported relying on self-regulation, such as TT1:

Implementing the new curriculum for four-year degree colleges is a transition period. I have to learn a lot about how to teach the new curriculum to the student teacher because my colleagues are too busy to share their ideas, and all are pursuing studies for their Master's and PhD degrees locally and abroad.

As less experienced teacher trainers, TT3 and TT4 reported that they usually conducted a lesson study with the heads of their departments and with experienced colleagues before delivering their lessons in the classroom, although they both preferred to study on their own when possible. TT5 and TT9 recognized that they learned through reading books, watching online video tutorials, imitation, observation, and reflection, but they did understand that collaborative learning should also be practiced. They are considered strong lifelong learners since they are more inclined to pursue lifelong learning if they believe they have great self-regulatory learning capacity (Nacaroglu et al., 2021). Overall, the respondents showed noteworthy differences in their learning strategies. Two preferred collaborative learning with their colleagues because they heard about different ideas; they sought training in newer curricula and school support to improve their teaching competencies. TT12 also said, "I prefer formal learning and expect the organizational arrangement as I cannot decide the appropriate training informally."

All the teacher trainers reported that their teaching competencies were also related to their lifelong learning competencies; for instance, they said they had improved while studying to improve their teaching competencies. Some teacher trainers reported significant improvements in their literacy, multilingualism, and cultural awareness competencies, attributing their improved literacy and multilingualism skills to the fact that they continued learning Burmese while they were also using English textbooks and teacher manuals; meanwhile, because the new curricula had been developed based on diverse cultures, the teacher trainers' cultural competence also increased. Separately, the teacher trainers reported apparent increases in their entrepreneurship competence as they learned to apply new teaching methods and create teaching learning resources. The teacher trainers in this study reported that their digital competence had improved when their new curricula included opportunities to apply their digital skills to their teaching practice. However, one teacher trainer felt her student teachers had greater digital competence than hers.

Some of the teacher trainers in this study offered suggestions for enhancing both teaching and lifelong learning competencies, including the following:

Teacher trainers should be pre-assessed for particular competencies before undergoing formal training.

Training must be conducted by experts who have experience in the field.

More than training is needed; practical experience is necessary as well.

Digital competence is crucial, so teacher trainees should have access to computers.

A post-training assessment should also be conducted.

Focusing on good health and engaging in reflective thought is more important, but it has nothing to do with their time.

Teacher trainers should be interested in lifelong learning and should regularly evaluate themselves.

It is essential to be aware of and pay attention to lifelong learning.

Supportive learning communities and incentives such as promotions are essential for improving lifelong learning.

Improving one's lifelong learning competencies will entail challenges.

These recommendations made by the teacher trainers are consistent with the findings of the previous studies. For example, Klug et al.(2014) listed the controllable factors for the lifelong learning model. Training, experience, and reflection are changeable facets of their studies on lifelong learning. Assessment is also a fostering factor for lifelong learning (Matsumoto-Royo et al., 2022).

Influencing Factors on Teacher Trainers' Lifelong Learning Competencies

Two main themes emerged from all the responses of the teacher trainers, each of which highlighted the influencing factors on lifelong learning competencies. These two themes revealed that all of the teacher trainers reported being influenced by both internal and external factors regarding their lifelong learning competences, as reflected in Table 2.

Table 3. Internal and external influences on lifelong learning competences

|

Internal factors |

External factors |

|

Confidence Interest Self-regulated learning Attitude and performance Intelligence Awareness Laziness Loving profession Health Afraid Practice and Habits Genetics Enthusiasm |

Promotion Chance to apply in the teaching Profession First teacher Family background Workload Time management Previous job experience Opportunities to learn Training Pre-and post-assessment Collaborative learning New curriculum Challenges Supportive learning community Shortage of teacher trainers COVID-19 |

Internal and external elements are considered as the individual variables in the study of Shin & Jun (2019), including administrative position experience, lifelong learning experience, learning agility, learning motivation, and positive mental assets. They also discovered that these individual characteristics can significantly explain the variations in lifelong learning competence among schools. Additionally, they noted that the socio-psychological variables substantially impacted lifetime learning competencies more than the demographic variables provided. Considering the present study's overall results, it can also be concluded that internal and external factors fall under socio-psychological variables. Due to this, background factors such as age and gender had less impact on lifelong learning competencies.

Although my interview was designed to emphasize these 12 teacher trainers' professional competencies and their development of lifelong learning competencies, only a few expressed personal development as well: "Having experienced the pandemic, I realize there are things we cannot control, so we must accept them, forgive ourselves and others, and become more understanding" (TT1) and "I have become more entrepreneurial and courageous because of the pandemic, and I see the potential in planning a second job outside teaching" (TT11). Their opinions align with the literature of Smith (2015) and Shrestha et al. (2008), who determined that lifelong learning had different dimensions, including a personal component, and called this process horizontal integration: a process during which learning activities are harmonized.

Limitations and Suggestions

This study has some limitations. First, because we developed the interview questions based on the results of previous, specific quantitative studies, they cannot be generalized to guide a comprehensive interview protocol for international contexts. Second, we applied purposive sampling, but influences of particular phenomena are particular to the participants in a study, which means the experiences of these 12 teacher trainers again might be different from broader populations. In addition, there could be other internal and external influences on lifelong learning competencies that we did not identify; for that reason, we propose that future researchers investigate the possible factors that influence teacher lifelong learning competencies both in Myanmar and worldwide. It is also important to note that we intended to explore teacher trainers' qualitative perceptions of their lifelong learning competencies with this study, and we did not quantitatively measure their actual lifelong learning competencies. However, our study highlights the need to build tests to assess the levels of lifelong learning competencies.

Conclusion

The present study explored more possible factors that can influence the lifelong learning competencies of teacher trainers. First, it revealed that teacher trainers perceived lifelong learning as learning to keep current with contemporary developments, focusing on their teaching profession. None of them are aware that a person's ability to engage in lifelong learning can be assessed using eight essential competencies. However, they reported that their highest competencies while the lowest are their scientific and mathematical competence and entrepreneurial and multilingual competence. They stated that their competence for learning to learn, literacy, multilingual, and digital were at the highest level of their list, while their competence for science and math and entrepreneurial and multilingual were at the bottom. Secondly, it found that most teacher educators hold the opinion that no factor, including gender, age, region of the education degree colleges, educational level, or area of employment, may affect the level of their lifelong learning competencies.

Additionally, their learning community changed due to the pandemic, which affected their digital and multilingual competence. Fourth, teacher trainers practiced self-directed learning and collaboration to improve their teaching competencies. As a result of this approach, their lifelong learning competencies are also enhanced. These findings reveal that internal and external factors significantly shape teacher trainers' lifelong learning competencies in Myanmar. The study results can be used to establish a strategic road map for lifelong learning, arrange professional development training in the light of lifelong learning, and promote each of the lifelong learning competencies in Myanmar.

References

Adabaş, A. & Kaygin, H. (2016). Lifelong Learning Key Competence Levels of Graduate Students. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(12A), 31-38. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2016.041305

Ayanoglu, C. & Guler, N. (2021). A study on the teachers' lifelong learning competencies and their reading motivation: Sapanca sample. University of South Florida M3 Center Publishing, 3(2021), 3. https://www.doi.org/10.5038/9781955833042

Bath, D. M. & Smith, C. D. (2009). The relationship between epistemological beliefs and the propensity for lifelong learning. Studies in Continuing Education, 31(2), 173-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/01580370902927758

Bozat, P. & Bozat, N. & Hursen, C. (2014). The Evaluation of Competence Perceptions of Primary School Teachers for the Lifelong Learning Approach. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 140, 476-482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.456

Buysse, V. & Sparkman, K. L. & Wesley, P. W. (2003). Communities of practice: Connecting what we know with what we do. Exceptional Children, 69(3), 263-277. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290306900301

Buza, L. & Buza, H. & Tabaku, E. (2010). Perceptıon of Lifelong Learning In Higher Education. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 26, 42-51. http://www.scientiasocialis.lt/pec/files/pdf/vol26/42-51.Buza_Vol.26.pdf

Cachia, M. & Millward, L. (2011). The telephone medium and semistructured interviews: A complementary fit. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 6(3), 265-277. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465641111188420

Commission, E. (2018). Report on a literature review of reforms related to the 2006 European Framework of Key Competences for Lifelong Learning and the role of the Framework in these reforms. Publications Office. https://doi.org/doi/10.2766/533014

Commission, E. (2019). Key competencies for lifelong learning. Publications Office. https://doi.org/doi/10.2766/569540

Commission, E., Directorate-General for Education Sport and Culture, Y., & Directorate-General for Employment, S. A. and I. (2002). A European area of lifelong learning. Publications Office.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. In Educational Research (Vol. 4). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1d5ZzlgJuCrwAyLpdBeK5dhKMZTpE2HNb/view

Deveci, T. (2019). Interpersonal Communication Predispositions for Lifelong Learning: The Case of First Year Students. Journal of Education and Future-EGITIM VE GELECEK DERGISI, 15, 77-94. https://doi.org/10.30786/jef.358529

Deveci, T. (2022). UAE-based first-year university students' perception of lifelong learning skills affected by COVID-19. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 9(2), 279-306. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe.2069

European Commission. (2018). Proposal for a Council recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. In European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/education/files/annex-recommendation-key-competences-lifelong-learning.pdf

European Council. (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and the Council on key competencies for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Union, March 2002, 10-18. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:394:0010:0018:en:PDF

Grbich, C. (2022). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529799606

Grokholskyi, V. L. & Kaida, N. I. & Albul, S. V. & Ryzhkov, E. V. & Trehub, S. Y. (2020). Cognitive and metacognitive aspects of the development of lifelong learning competencies in law students. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education, 8(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.5937/IJCRSEE2002001G

Hord, S. M. (2004). Learning together, leading together: changing schools through professional learning communities. In Critical issues in educational leadership series (pp. viii, 184 p.). Teachers College Press. http://mirlyn.lib.umich.edu/Record/004358360

Klug, J. & Krause, N. & Schober, B. & Finsterwald, M. & Spiel, C. (2014). How do teachers promote their students' lifelong learning in class? Development and first application of the LLL Interview. Teaching and Teacher Education, 37, 119-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.09.004

Kuzu, S. & Demir, S. & Canpolat, M. (2015). Evaluation of Life-Long Learning Tendencies of Pre-Service Teachers in Terms of Some Variables. Journal of Theory and Practice in Education, Eğitimde Kuram ve Uygulama Articles /Makaleler 11(4), 1089-1105. https://doi.org/10.17244/EKU.09104

Lavrijsen, J. & Nicaise, I. (2017). Systemic obstacles to lifelong learning: the influence of the educational system design on learning attitudes. Studies in Continuing Education, 39(2), 176-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2016.1275540

Matsumoto-Royo, K. & Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. & Glasserman-Morales, L. D. (2022). Lifelong Learning and Metacognition in the Assessment of Pre-service Teachers in Practice-Based Teacher Education. Frontiers in Education, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.879238

Muller, R., & Beiten, S. (2013). Changing learning environments at university? Comparing the learning strategies of non-traditional European students engaged in lifelong learning. Journal of Educational Sciences & Psychology, 65(1), 1-7.

Nacaroglu, O., Kizkapan, O., & Bozdag, T. (2021). Investigation of Lifelong Learning Tendencies and Self-Regulatory Learning Perceptions of Gifted Students. Egitim ve Bilim, 46(205), 113-135. https://doi.org/10.15390/EB.2020.8935

Pilli, O., Sönmezler, A., & Göktan, N. (2017). Pre-Service Teachers' Tendencies and Perceptions towards Lifelong Learning. European Journal of Social Sciences Education and Research, 10(2), 326. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejser.v10i2.p326-333

Sahin, M. & Akbasli, S. & Yelken, T. Y. T. Y. (2010). Key competencies for lifelong learning: The case of prospective teachers. Educational Research and Reviews, 5(10), 545-556. http://www.academicjournals.org/ERR2

Seah, S. & Lin, J. & Martinus, M. & Suvannaphakdy, S. & Thi, P. & Thao, P. (2023). Southeast Asia 2023 Survey Report. www.iseas.edu.sg

Selvi, K. (2010). Teachers' competencies. Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of Culture and Axiology, 7(1), 167-175. https://doi.org/10.5840/cultura20107133

Sen, N. & Durak, H. Y. (2022). Examining the Relationships Between English Teachers' Lifelong Learning Tendencies with Professional Competencies and Technology Integrating Self-Efficacy. Education and Information Technologies, 27(5), 5953-5988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10867-8

Şentürk, C. & Baş, G. (2021). Investigating the relationship between teachers' teaching beliefs and their affinity for lifelong learning: The mediating role of change tendencies. International Review of Education, 67(5), 659-686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-021-09917-7

Shin, Y.-S. & Jun, J. (2019). The hierarchical effects of individual and organizational variables on elementary school teachers' lifelong learning competence. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 12(2), 205-212. https://doi.org/10.26822/iejee.2019257668

Shrestha, M. & Wilson, S. & Singh, M. (2008). Knowledge networking: A dilemma in building social capital through nonformal education. Adult Education Quarterly, 58(2), 129-150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713607310149

Smith, C. R. (2015). Continuous Professional Learning Community of Mathematics Teachers in the Western Cape: Developing a Professional Learning Community Through a School-University Partnership. In Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape. (Issue November). University of the Western Cape.

Steffens, K. (2015). Competences, learning theories, and MOOCs: Recent developments in lifelong learning. European Journal of Education, 50(1), 41-59. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12102

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques (2nd ed). Sage Publications, Inc.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237-246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

Thompson, S. C. & Gregg, L. & Niska, J. M. (2004). Professional Learning Communities, Leadership, and Student Learning. RMLE Online, 28(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2004.11658173

Thwe, W. P. & Kálmán, A. (2023a). Relationships between the perceptions of lifelong learning, lifelong learning competencies, and learning strategies by teacher trainers in Myanmar. International Review of Education, 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-023-10029-7

Thwe, W. P. & Kálmán, A. (2023b). The regression models for lifelong learning competencies for teacher trainers. Heliyon, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13749

Vaismoradi, M. & Snelgrove, S. (2019). Theme in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3376

Xiao, S. & Saedah, S. (2015). Professional learning community in education: Literature review. The Online Journal of Quality in Higher Education, 2(2), 65-78.

Yen, C. J. & Tu, C. H. & Sujo-Montes, L. E. & Harati, H. & Rodas, C. R. (2019). Using personal learning environment (PLE) management to support digital lifelong learning. International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design, 9(3), 13-31. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJOPCD.2019070102

Yildiz-Durak, H. & Seferoglu, S. S. & & Sen, N. (2020). Some personal and professional variables as identifiers of teachers' lifelong learning tendencies and professional burnout. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 15(2), 259-270. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v15i2.3797

Zuhairi, A. & Hsueh, A. C. T. & Chiang, I.-C. N. (2020). Empowering lifelong learning through open universities in Taiwan and Indonesia. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 15(2), 167-188. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-12-2019-0059.