Moet Moet Myint LAY

Quality teacher education: a review of professional learning community

Introduction

The role of education in society is often at the center of the debate over what constitutes quality education. One important function of education is that it is viewed as essential to concepts of human development on a global scale. For instance, since the 1990 launch of the United Nations Human Development Report series, education has served as an indicator for determining levels of human development (United Nations Development Programme 1990).

According to Kuhn, the paradigm is necessary for scientific research because "no natural history can be interpreted in the absence of at least some implicit body of interconnected theoretical and methodological the idea that permits selection, evaluation, and criticism, that permits selection, evaluation, and critique." A shift in professional commitment to shared assumptions occurs when the fundamentals of current scientific practice diverge. Kuhn refers to these events as scientific revolutions because "the tradition-shattering complements the tradition-bound work of normal science." The reconstruction of earlier assumptions and the reevaluation of earlier facts are necessary for "new assumptions", or "paradigms” (Kalman, 2016).

Regarding the professional development of teachers, a paradigm change has been gaining momentum during the past 20 years. This reform expands professional development beyond merely assisting teachers' acquisition of new information and abilities, driven by the complexity of teaching and learning in an environment of rising accountability. According to Darling-Hammond and McLaughlin (1995), the nation's reform program needs most teachers to reconsider their practice, establish new classroom roles and expectations concerning student outcomes, and teach in ways they have never taught before (Darling Hammond, 1995).

Little (1982) also discovered that planning, developing, conducting, analyzing, assessing, and experimenting with the business of teaching were the collegiality norms (faculty working together) that were most effective in fostering professional progress. Teachers are more willing to participate in professional development when they recognize that their colleagues have something new to contribute and that doing so would help them advance their careers (Little, 1982).

In 2009, EU education ministers announced the EU strategy 2020 to link education and business to the European Year of Creativity and Innovation, with a focus on quality assurance and development for teachers under European policy (Halasz, 2013). The main component of the Lifelong learning policy is value learning (such as creating a learning community and facilitating access to learning opportunities), information, guidance, and counseling (such as creating a learning culture and partnership working), investing the time and money in learning, promoting the learners and learning opportunities, and basic skills and innovative pedagogy (European Communities, 2008). Several authors have emphasized the significance of the process of self-directed learning. Self-management, self-monitoring, and self-reflection allow both students and teachers to have a more comprehensive understanding of what needs to be changed and improved in their methods and conduct. The approach is based on the notion that reflective learning methods are crucial for lifelong learners (Kalman and Citterio, 2020).

The teacher community includes improving the quality of teachers for analyzing and designing management at the macro, meso, and micro levels. Most of the schools needed continuous professional development (CPD) programs that offered individual teachers through knowledge-sharing communities or school networks or support incentives. Schools can be encouraged to improve the behavior of the teacher and the student learning outcomes which makes a professional identity, and a professional learning environment (European Commission, 2015).

Literature Review

According to Hord (2009), a professional learning community is defined in words.

Professionals: Those who are reliable and accountable for providing students with a successful educational program so that they can all learn successfully. Professionals share responsibility for this goal and come prepared with a fierce commitment to both their own and the student's learning.

Learning: an activity in which professionals can immerse themselves to Improve their knowledge and skills.

Community: A community is made up of people who get together in a group to engage in serious conversations with one another about a particular subject, create a sense of shared purpose, and establish shared meaning.

Professional learning communities are created by combining the ideas of professional learning and community. A PLC is described as a group of educators that collaborate continuously to share, research, and reflect on their professional practice to promote student learning and school improvement (Hord, 1997; Stoll et al., 2006).

A professional learning community (PLC) is a group of educators that critically examine and evaluate their teaching practices through reflection and collaboration. It also has to be focused on student learning. Teachers who actively participate in PLCs will improve their professional knowledge by improving the quality of student learning (Toole & Louis, 2002).

Table 1. Effective Dimensions of Professional Learning Community (PLCs)

|

1997 |

1998 |

2003 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Hord (1997) described as PLCs: (1) Shared values & vision (2) Supportive & Shared leadership (3) Collective Creativity (4) Shared personal practice (5) Supportive conditions |

Dufour and Eaker (1998) classified as: (1) Shared Mission Vision, Value & Goals (2) Collective Inquiry (3) Collaborative Culture (4) Action Orientation (5) Commitment to Continuous Improvement (6) Results Orientation

Other perspectives of Wenger (1998): (1) Shared repertoire (2) Mutual engagement (3) Joint enterprise |

Huffman and Hipp (2003) defined as: (1) Shared Values and Vision (2) Shared and Supportive Leadership (3) Collective Learning and Application (4) Shared Personal Practice (5) Supportive Conditions |

Meeuwen, et al. (2020) stated as: (1) Lessons/teaching practice (2) Communities of Practice (COPs) (3) Collective learning (4) Professional orientation |

Tai and Omar (2018) explained as: (1) Shared Norms and Vision (2) Principals’ Commitment & Support (3) Structural Support (4) Collegial Understanding & Trust (5) Collaborative Learning (6) Reflective Dialog (7) Collective inquiry (8) External Support System. |

Method

This article is of the systematic review type, intending to explore the importance of professional learning communities for the professional development of teacher education. It is also aimed to provide a comprehensive perspective on the importance of a professional learning community.

These include PRISMA, resources, the process of systematic review, as well as data abstraction and analysis that were adopted in the present study.

Search strategy

A manual for writing this systematic literature review is PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) (SLR). This approach is a guideline for a qualitative assessment of the literature because it is a labor-intensive and detailed process that involves a lot of data. PRISMA's strength is its capacity to generate qualitative research reports using specific procedures that exhibit transparency, consistency, and high-standard components (Flemming et al., 2019). Researchers can create publications for analysis on websites like Scopus, Google Scholar, ERIC, Springer Link, Academia and Science Direct, but each of these articles must first pass through a screening process. All of the chosen articles are then thoroughly read after that. The author's name, the article's title, the publication date, the objectives, the research methodology, the findings, and the conclusions are all systematically noted. The next section then discusses details information on the study of papers.

Inclusion criteria for selecting the articles

The literature collected from the search process must go through several screening and categorization processes. Screening is a process that defines inclusion and exclusion criteria that the author can use to select articles or references that fit the SLR to be formed. The study inclusion criteria for systematic reviews are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The inclusion criteria of the study

|

Criterion |

Criteria |

|

Timeline |

2018-2022 |

|

Language |

English |

|

Study scope |

-Concepts of professional learning community -Dimensions or Characteristics of professional learning community |

|

Type of Literature |

Journal (research articles) |

Source: Adapted from Pandian et al. (2022)

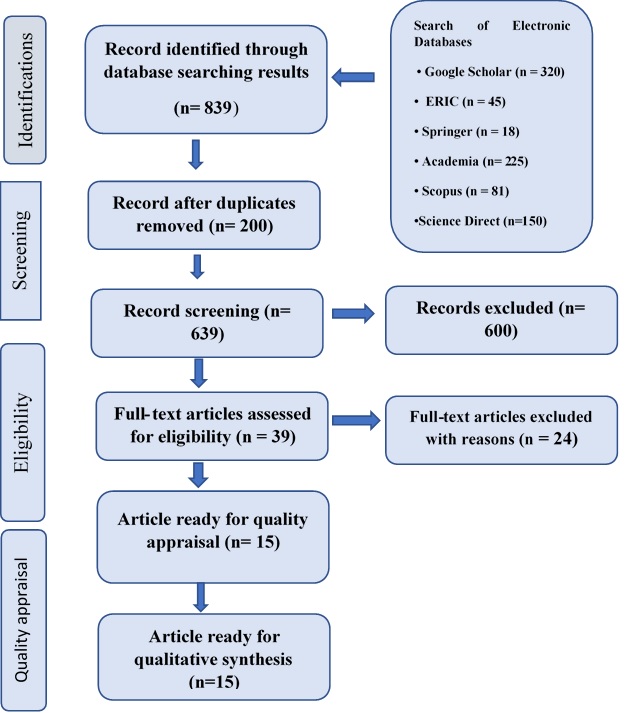

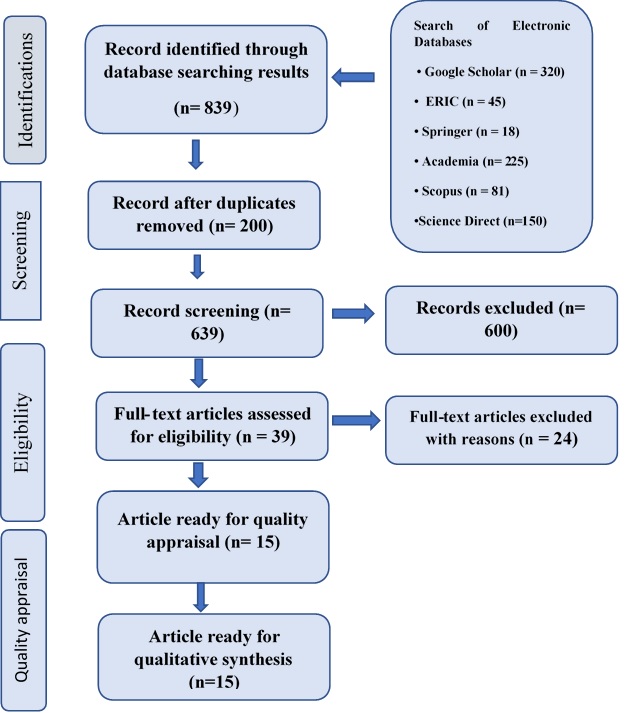

Identification of the study

The four primary stages of the systematic review procedure went into selecting the linked articles for this study. The main terms “Concepts of professional learning community”, and "dimensions of professional learning community” or “characteristics of professional learning community” were used to filter out articles that were relevant to the study. A total of 839 papers were collected from the systematic review process's initial phase.

Screening

During the initial screening phase, duplicate items were removed. Therefore, 639 papers were screened in the second phase using investigator-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria, as opposed to 600 articles that were excluded in the first phase. The researchers' decision to concentrate solely on the journal's research papers, which serve as the primary source of empirical data, was the first criterion.

The next stage of screening involved reviewing the titles to exclude papers that did not meet inclusion criteria, book series, books, book chapters, and reports that were related to engineering or medical papers, such as topic relevance. For example, title such as “Design conversations and informal chats: ‘situated’ professional development, learning community, and casual tutors in undergraduate architectural design education.”

Eligibility

The next process is to conduct eligibility on the remaining 39 articles selected from the screening process earlier. An amount of 24 articles were omitted as the emphasis was not on the concepts of professional learning community or dimensions. Finally, 15 articles were selected to proceed to the quality assessment stage of the procedure based on this process. The review is based on a total of 15 journal articles published between 2018 and 2022 that satisfied the inclusion requirements (see Figure 1). A preset data extraction form was used to extract the data. Each paper's completed form included information about the author, year, country, research focus, research design, methodology, participants, and major findings. This method gave confidence that enough precise data was extracted.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram

Source: Adapted from Hayrol et al. (2019)

Findings

Table 3. Details information on the study of papers

|

Author, year |

Country |

Study focus |

Research design and methodology |

Participants |

|

Oppi, P., & Eisenschmidt, E. (2022) |

Estonia |

Professional learning community through teacher leaders

|

Case study and twice interviews (January–February 2021 and in December 2021–January 2022). |

Three teacher leaders and three participating teachers (Estonian school). |

|

Amanda Scull(2021) |

USA |

Creating community, learning together for staff professional development. |

Quantitative Survey. |

15 staff members. |

|

Brown, C., & Flood, J. (2020) |

England |

Roles of school leaders in maximizing the impact of Professional Learning Networks. |

Case study and interviews. |

Senior Leader(n-=13) and Opinion Former(n=8), Total (n=21) from 8 primary schools situated in the New Forest area of England. |

|

Antinluoma, M., Ilomäki, L., Lahti-Nuuttila, P., & Toom, A. (2018) |

Finland |

Building professional learning communities for improvement of teachers’ professionalism. |

Quantitative study. |

8 principals, 11 assistant principals, 122 class teachers, 78 subject teachers, (total of 212). |

|

Meeuwen, P. V., Huijboom, F., Rusman, E., Vermeulen, M., & Imants, J. (2020) |

Netherlands |

Teachers’ professional development focuses increasingly on professional learning communities (PLCs). |

Literature review and Qualitative study of interviews. |

12 semi-structured interviews (school leaders =5, advisors =2, researchers=2, inspectors =2, policy advisor=1). |

|

Admiraal, W., Schenke, W., De Jong, L., Emmelot, Y., & Sligte, H. (2021) |

Netherlands |

School as professional learning communities to support professional development of teachers. |

Focus groups interviews. |

14 secondary schools during three school years (School year 1 (2014–15), School year 2 (2015–16), and School year 3 (2016–17) No of teachers =2615, No of students=20605. |

|

Belay, S., Melese, S., & Seifu, A. (2022) |

Ethiopia |

Elevating collaborative professional learning provides the teacher with individualized professional learning, and job satisfaction in their professional capital development. |

Quantitative Survey

|

379 teachers randomly selected from Awi district primary schools, Ethiopia. |

|

King, F., & Holland, E. (2022) |

Ireland |

Professional learning model support leadership learning and growth of early career teachers. |

Qualitative study and literature review.

Data was collected from e-technology interaction, audio-visual workshop recording, and artifact generation and collection such as upload TSAPs, Talking Heads videos, and other reflective processes and activities. |

Seven early career teachers interview.

The data which were gathered from teachers’ participation during and between the first eight “Leadership for Inclusion” CoP [LIn-CoP] workshops of the study (between November 2017 and April 2021). |

|

Yeol, L. S. (2020) |

South Korea |

Analysis of the Effect of School Organizational Culture and Professional Learning Communities on Teacher Efficacy. |

Survey Descriptive statistics (T-test the F-test and Scheffe test). |

400 teachers (in-service teachers) were surveyed from a total of 15 schools located in Daejeon, Chungnam, and Gyeonggi (5 schools from each region). |

|

Saydam, D. (2019) |

Turkey |

Teachers’ beliefs on the impact of Professional Learning community. |

A qualitative exploratory case study. |

Semi-structured individual interviews of the selected English language teachers (n=4) at public university in Turkey.

|

|

Johannesson, P. (2020) |

Sweden |

Development of professional learning communities through understanding professional learning in practice. |

A case study of an upper secondary school in Sweden. |

18 teachers interviewed in the learning groups in the school.

|

|

Vella, R., & Azzopardi, J. A. (2021) |

Malta |

Effective Continuing Professional Learning and Development of the teachers. |

Mixed method approach

The quantitative data collected, the research literature, and the qualitative data were examined and cross-referenced.

The quantitative study used descriptive statistics (the Chi-Square test and the Friedman test) and IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software. |

360 mathematics teachers form the state and non-state schools at all secondary school sectors in Malta and Gozo. (261 teachers in 21 Church, 3 Independent and 22 State middle and secondary schools). |

|

Brown, B. D., Horn, R. S., & King, G. (2018) |

USA |

The Effective Implementation of Professional Learning Communities. |

Literature review (Positive school reform). |

Previous STEM research (PLCs, project-based learning, sustained professional development, and K-12 the partnership was implemented by a team of researchers from Texas A&M University (2016). |

|

Antinluoma, M., Ilomäki, L., & Toom, A. (2021) |

Finland |

Practices of Professional Learning Communities. |

Qualitative multiple-case study. |

School A: one municipal primary school with classes 1–6,

School B: one municipal primary school with classes 1–5,

School C: one municipal primary school with classes 1 and 2, and

School D: one private comprehensive school with classes 1–9 (primary school section with classes 1–6 and secondary section with classes 7–9)

Interviews purposive sampling -12 individuals (four principals and eight teachers). |

|

Jafar, M. F., Yaakob, M. F. M., Awang, H., Zain, F. M., & Kasim, M. (2022) |

Malaysia |

Professional Learning Community (PLC) improves teachers’ effectiveness by reconnecting Educational Policy with School Culture. |

A cross-sectional survey method (a correlational design). |

612 teachers using Professional Learning Community Assessment (PLC-A) (Olivier, Hipp & Huffman, 2010). |

Table 4. Outcomes of each review paper studies

|

Author, year |

Findings |

Comments |

|

Oppi, P., & Eisenschmidt, E. (2022) |

Teachers invested a lot of time in learning the theory, and based on their shared comprehension, they created a model to assist students in defining goals. The teacher leaders acknowledged that running the PLC could be challenging at times, but they decided to carry on the following year, nevertheless. However, teacher leaders’ self-initiative was insufficient to guarantee the PLC's effective implementations. The viability of the PLC was hampered by the school leadership team's lack of interest and support (for example, previously designated time for collaboration was eliminated). |

This case study shows that the viability of a PLC requires the interest and support of the school leadership team. If there is no support from the school leadership, the PLC could be challenging. |

|

Amanda Scull (2021) |

Conferences, webinars, online courses and peer discussion are all excellent options for one-time professional development in the library community. These are priceless and significant opportunities that should be promoted to staff members. It has been demonstrated to be a great method to create a culture of learning, sharing, and professional development to design and implement a systematic program of staff development that combines the knowledge of all staff, promotes social learning as a group, and adopts a variety of learning styles. |

It is clear that building a learning community, and learning together, among other things, can significantly support an employee's professional skill development. |

|

Brown, C., & Flood, J. (2020) |

The first-order variables that the school leaders focused on were formalizing RLN involvement by including it in the school improvement plan, involving governors to track progress and provide funding (for teacher release, for example), and integrating the process into teachers' performance management goals. Such instructional leadership acts were crucial in affecting the factors that can directly affect the effectiveness of instruction and the learning of students. The implementation of an intra-school PLC by School N ensured the development of a whole-school collaborative approach. The interaction between the intra-school PLC and the RLN reflected the coordination of professional learning model effects that created significant ties between the network and the school. |

School administrators must use best practices in these fields after deciding whether mobilization should be accomplished through the development of a PLC or through a more general brokerage in order to make sure mobilization happens as successfully as possible. The role of school leaders is critical in maximizing the impact of Professional Learning Networks. The importance of supportive & shared leadership can be seen as described in Hord's (1997) professional learning community model. |

|

Antinluoma, M., Ilomäki, L., Lahti-Nuuttila, P., & Toom, A. (2018) |

According to the participants' perceptions, all schools have a culture of cooperation, commitment, and trust. Teachers could collaborate professionally because the school cultures encouraged it and because they had the necessary knowledge, abilities, and attitudes. The difficulties were brought on by structural issues, particularly the lack of collaborative time. In the cluster analysis, three school profiles that may be considered professional learning communities from the perspective of maturity were found. Organizational and operational characteristics were found to differ between the three clusters statistically significantly. |

To further our understanding of PLCs, as proposed by Hord et al. (1999), research that combines qualitative data with case studies of effective PLCs and successful progressions linked to enhanced learning outcomes is required. To better comprehend the PLC idea, the relationships between the dimensions, and the roles played by the students, more research is also required. The further understand how schools evolve into PLCs, more extensive long-term follow-up research should be conducted. |

|

Meeuwen, P. V., Huijboom, F., Rusman, E., Vermeulen, M., & Imants, J. (2020) |

An extensive variety of visible PLC characteristics and a wide range of external influencing factors were revealed by the literature review and the interviews. According to expert interviews, the framework didn't appear to be missing any critical components, and a lack of framework viewpoints was mentioned. The PLCs framework was confirmed by the recent literature. The authors concluded that the created PLC concept is sufficiently thorough and workable for performing PLC research. This study explored PLC characteristics: (1) Collaboration (2) Reflection (3) Giving and receiving feedback (4) Experimenting (5) Mutual trust and respect (6) Collegial support (7) Social cohesion (8) Shared vision (9) Shared responsibility (10) Shared focus on student learning (11) Shared focus on continuous teacher learning. |

The framework can be used to discuss how the various PLC characteristics are coming along or to identify obstacles to professional development. In conclusion, the conceptual framework can help ensure that PLC in schools is implemented and maintained over time. |

|

Admiraal, W., Schenke, W., De Jong, L., Emmelot, Y., & Sligte, H. (2021) |

The activities in five groups can be used to describe the interventions 14 secondary schools implemented to create, support, and further develop as PLC: 1) Shared school vision on learning; 2) Professional learning opportunities for all staff; 3) Collaborative work and learning; 4) Change of school organization, and 5) Learning leadership. Interventions focused on team leaders, school principals, and teacher leaders were comparatively uncommon. The interventions that focused on Collaborative work and learning and Professional learning opportunities were the most commonly acknowledged. The structural integration of teacher groups into the structure of the school was valued for its connection between work and learning. In general, the authors drew the conclusion that an intervention's impact is more long-lasting and helps move schools toward a culture of professional learning and collaboration the more deeply it is ingrained in the structure and culture of the institution. |

These school interventions were organized around the idea of the school as a professional learning community. Opportunities for professional development and collaborative work and learning, including formal and informal teacher groups working and learning together, were the ones most frequently highlighted. The authors concluded that shifting schools toward a culture of professional learning community and collaboration improve teacher learning and development. |

|

Belay, S., Melese, S., & Seifu, A. (2022) |

Based on predetermined criteria, the measurement model and structural model displayed a satisfactory fit. The results demonstrated a substantial relationship between teachers' job happiness, participation in individualized and collaborative learning, and their professional capital development. These independent variables explained 68.3% of the variation in professional development, leaving 31.7% of the variation unexplained. The study's result emphasized the significance of teacher-level collaboration in boosting professional capital in the teaching field. |

Collaborative work among teachers for learning and exchanging professional learning and job satisfaction may be a particularly effective and practical professional development. Collective learning is seen as the key factor to professional development and building a professional learning community. |

|

King, F., & Holland, E. (2022) |

This development is not linear, but rather iterative and recursive, primarily focused on personal progress, supported by collaborative contacts and discourse. It gives specific examples of advancement in various areas and confirms this. To support teacher personal growth trajectories while also realizing that this growth is influenced by teachers' personal and contextual problems, needs, and desires, this study highlights the range of evolving interactions between growth components and between growth results. The lack of research on teacher leadership and professional learning approaches to support teacher leadership is addressed in this paper as a first step. |

In using the framework within PLCs, schools need teacher leadership development. Poekert et al. ’s (2016) framework, empirical findings support potential leadership learning within a school-university partnership model. Finally, this paper is considering professional learning for teacher leadership development. It was crucial to adopt a proper model of professional learning to support this given the emphasis on feedback loops and interactions as necessary for progress as a researcher, teacher, leader, and personal growth. |

|

Yeol, L. S. (2020) |

The organizational culture of a school is first changing and developing into a more ideal and model culture. Inventive cultures and group cultures are forming as schools get more and more innovative. Second, a school is a form of organizational structure that stimulates different responses from instructors based on their individual backgrounds and traits. Third, teacher efficacy is enhanced by professional learning communities. This study stated that school organizational culture rather than a professional learning community can be used to predict teachers' effectiveness. |

The professional learning community becomes more active, particularly when inventive and group culture are employed, and when these factors are combined, the teacher's efficacy rises. In this situation, it is essential to develop an organizational culture within the school and to place a strong emphasis on the professional learning community as a driver of change. It is important to note that professional learning communities operate better jointly than school organizational culture alone to promote teacher efficacy. |

|

Saydam, D. (2019) |

The results of an exploratory case study conducted with four English language teachers at a public university in Turkey are revealed after a thematic review of studies on the acquisition of professional knowledge, the scope of professional knowledge, beliefs on professional learning experiences, and the impact of learning experiences on classroom practice. The findings highlight the environments in which teachers learn, the kinds of learning experiences they had in their early and more recent years of practice, views about teacher learning, and how that learning impacts practice. |

Additionally, the current study does not look at the difficulties instructors encounter while pursuing professional growth or the causes of those difficulties. This may enhance instructors' opportunities for professional learning and encourage those who might not otherwise participate in professional development events. Teachers believe that teaching and learning will improve by engaging teachers in professional learning activities and experiences. Therefore, teachers need a community that can create teaching and learning opportunities for teachers’ professional development. |

|

Johannesson, P. (2020) |

According to studies, teachers who participate in action research build a common repertoire of skills that is relevant to both local requirements and the field and traditions of action research. The repertoire also makes it easier for teachers to work together. Mutual engagement in the learning groups is, however, impacted by varying interpretations of the project. This shows that a lack of congruence between local practice and action research practice affects group dynamics and could barriers the growth of a PLC. It is feasible to define and make visible the professional learning community in practice, including the repertory that teachers acquire, how they collaborate on works, and the objectives they strive towards, by employing theoretical notions (as in this example). |

Thus, educational researchers and educators need to support the teacher-learning community to achieve their goals rather than adopting an action research strategy that dictates scientific validity. Supporting schools will bring them closer to being effective teacher-learning communities. |

|

Vella, R., & Azzopardi, J. A. (2021) |

All of the teachers who participated in the study's survey said they valued professional development and saw it as essential to their ability to do their jobs well. Teachers believe that professional development (PD) gives them the chance to continuously learn new information and to improve their abilities and pedagogical methods. According to the research's findings, PD activities for math teachers are most successful when they extend beyond a single meeting or session. Several teachers (60.6%, 58.3%, and 58.2%, respectively) believe that school-organized sessions, consultation meetings, and professional learning communities offered by MEDE have a moderate to high impact on their professional development. Attending seminars designed exclusively for math teachers is also seen favorably (79.6%). According to research, teachers are inspired to participate in professional development when their needs are taken into account, their knowledge is recognized, and their classroom practices and initiatives are incorporated into the professional learning experience. |

According to this study, school-level collaboration is very advantageous for teachers because it fosters greater teacher engagement and communication as well as chances for assistance among instructors. This study illustrated the power of teachers' research and collaboration practices to generate new concepts and methods. This study aims to summarize the opportunities of a good learning environment for the current professional development of mathematics teachers in Malta, based on teachers' self-perceptions, a subject in great need of research in the region. |

|

Brown, B. D., Horn, R. S., & King, G. (2018) |

The implementation of grade-level professional learning communities and the support provided to teachers in the four elementary schools were surveyed. Qualitative and survey data showed that principals influenced what teachers in PLCs do and how successfully they carry out those undertakings (Buttram & Farley-Ripple, 2016). As a result, Buttram and Farley-Ripple (2016) contributed to the understanding of the significance of the role of principals in embracing reform efforts like professional learning communities and successfully implementing them in their schools. |

According to this study, Professional learning communities (PLCs) have improved education in recent years, from elementary school through college, with numerous positive effects. PLCs give teachers a setting that promotes innovation, cooperation, and professional growth. |

|

Antinluoma, M., Ilomäki, L., & Toom, A. (2021) |

The outcomes demonstrated that principals were primarily responsible for the development of schools into PLCs. Principals were characterized as inspiring figures of leadership who had sparked forward motion, distributed leadership, and fostered a sense of devotion to shared objectives. The outcomes also showed that a change in leadership could be beneficial. The goal of the collaborative, democratic, participatory, and inclusive decision-making processes was to reach a satisfactory level of consensus. Staff employees were reportedly free to voice their thoughts and relationships expressed mutual trust and transparency. Co-teaching, peer support, encouragement, and shared student responsibility were all used. One kind of collaborative work-embedded professional learning that is related to the fundamental ideas of professional learning communities has been identified as co-teaching practices. It was reported that structural issues were obstacles to schools becoming PLCs. |

Prior PLC research established capabilities that enable us to assess the school's PLC procedures. These findings showed that the interpersonal and organizational capacities of the participating schools' PLCs were reflected in their practices, but the study also highlights certain common and contextual obstacles within these capacities, such as resources and value clarity. The COVID-19 pandemic is currently having a severe impact on PLCs and schools around the globe. The scenario is testing PLC leadership, structures, teamwork, PLD, culture, and climate of PLCs. |

|

Jafar, M. F., Yaakob, M. F. M., Awang, H., Zain, F. M., & Kasim, M. (2022) |

One of the important factors that lead to PLC is sharing the planning element. Because it may give the PLC group members the best opportunity to share their lesson plans from the beginning of their induction set to the finish, the authors think that the sharing planning component will wind up being the most important one. The group members can work together to assess and determine the teaching plan's advantages and disadvantages. Based on the feedback they receive from the sharing process during PLC meetings, the teachers may make adjustments to and enhance their teaching methods and assessment in order to attain the desired learning results. The authors conclude from the findings that most teachers understand the idea of sharing planning. They might cooperate as a team to accomplish their organizational purpose. According to these findings, the second component that greatly contributes to the success of PLC among teachers is transformational leadership. Since PLC has been included in Malaysia's educational policies, it is imperative to reconnect educational policy to school culture. By taking part in school-supportive educational policies, teachers can contribute their skills and knowledge outside of the classroom. |

The PLC benefits from school culture, as evidenced by sharing planning and change leadership. This study adds something new to the body of knowledge by helping researchers identify the most important and influential aspects influencing teachers' PLC practices. |

Conclusions and Discussion

Concepts of professional learning community

DuFour (1998, 2004) discovered collective learning as a continuous process that promotes teacher professional development, student learning, and problem-solving in school. Studies show that the professional learning community helps teachers to develop subject-matter expertise, increase their knowledge, learn to collaborate, and enhance and improve student academic achievement and school quality (Admiraal et al., 2021, Belay et al., 2022, Yeol, L. S. (2020), Antinluoma et al., 2018, Johannesson, P. 2020). While many factors contribute to professional development, it is obvious that creating a learning community and learning together can greatly enhance the teacher's professional development (Amanda Scull, 2021). Moreover, a better understanding of the PLC concept can show successful developments linked to better learning outcomes due to effective PLC (Antinluoma et al., 2018). In order to exchange resources, learn from others who are encountering similar or dissimilar issues, and form strong networks with other teachers and schools, it is essential for individual schools to adopt the concepts of PLCs. Learning from colleagues is a cost-effective way to achieve continuous professional development. Sharing best practices let people learn from others' experience and gain insight into other viewpoints on the same situation. In this regard, evidence has shown the importance of establishing a professional learning community within the school as a foundation for the teacher's professional development or teacher efficacy.

Dimensions or Characteristics of professional learning community

Although the dimensions vary from one to another, the core dimensions of PLCs are (i) shared and supportive leadership, (ii) shared values and vision, (iii) collective learning and application, (iv) shared personal practice, (v) supportive conditions: relationships and structures (Hord, 1997; Huffman & Hipp, 2003). Amanda Scull (2021) indicated that teachers can enhance their professional development by participating in the collective learning process and professional development activities (e.g conferences, online courses, and peer discussions). Thus, it has made significant contributions to improving teaching practices. School leaders have succeeded in sharing and supportive leadership, creating the collective learning that support learning and professional development. However, school leaders set up the environment to encourage teachers' interactions in order to facilitate or support all these PLC characteristics. (Oppi & Eisenschmidt, 2022, Vella & Azzopardi, 2021, Brown & Flood, (2020), King & Holland, 2022, Saydam, 2019, Jafar et al., 2022).

Meeuwen et al., (2020) explored the main characteristic of PLCs is collaboration, reflection, providing feedback, testing, mutual trust and respect, special support, social unity, share responsibility, sharing a focus on student learning, and sharing a focus on continuous teacher learning. According to literature review, shared personal practice and certain supportive conditions have become an essential part of enhancing the professional learning community that promotes innovation, cooperation, and professional growth during implementation (Antinluoma et al., 2021).

PLC is embedded in Malaysian education policies and there is a need to reconnect education policy with school culture. It has become clear that PLCs can support teachers' skills and knowledge through inclusion in educational policies (Jafar et al., 2022). Therefore, schools come from a variety of backgrounds, and the Ministry of Education must coordinate a specific PLC model in the local context.

PLC process implementation was not a simple task. Support along the way is needed to realize and accomplish the community's goals. Through walkthroughs, formal and informal observation, and other methods, principals need to assist their teachers. In order to follow up and have a record of what the team accomplished during the meetings, school leaders required a meeting agenda and required meeting minutes. They also trained teachers in teaching methodology and instructed them to regularly use this technique in their teacher teams to adjust lesson plans to students' needs. Finally, the literature review shows that teacher leadership and professional learning communities are important for growth as a leader, a researcher, a teacher, and personal growth.

Challenges

PLC research is a continuous endeavor. Conceptual changes may arise from new theoretical understandings or the results of empirical studies. In that regard, it is a dynamic idea rather than a fixed one. The PLC implementation process presented certain difficulties. One is the unwillingness of some teachers to share their knowledge or accept help from their colleagues. The teams' work was impacted by this resistance because of disagreements that made decision-making difficult. However, disconnection from the team makes it more difficult to achieve success and job satisfaction at work.

Therefore, building Professional Learning Communities (PLC) is one of the most well-known methods for improving teacher quality, school improvement, and student achievement.

Limitation

This review has some limitations. First, only documents from 2018 to 2022 were included in the search, which was finished in 2022. For this reason, investigations conducted outside of this time frame were not considered. The second issue is that reporting may not adhere to accepted criteria for high quality, such as transparent and unambiguous reporting. This issue of quality reporting should be the focus of future research. Future research will follow established standards for good quality such as clear, systematic models and transparent reporting.

References

· Admiraal, W., Schenke, W., De Jong, L., Emmelot, Y., & Sligte, H. (2021). Schools as professional learning communities: what can schools do to support professional development of their teachers? Professional development in education, 47(4), 684–698.

· Antinluoma, M., Ilomäki, L., & Toom, A. (2021). Practices of professional learning communities. In Frontiers in education, 6(617613), 1–14. Frontiers. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.617613

· Antinluoma, M., Ilomäki, L., Lahti-Nuuttila, P., & Toom, A. (2018). Schools as professional learning communities. Journal of education and learning, 7 (5). ISSN 1927-5250 E-ISSN 1927-5269.

· Belay, S., Melese, S., & Seifu, A. (2022). Elevating Teachers’ Professional Capital: Effects of Teachers’ Engagement in Professional Learning and Job Satisfaction, Awi District, Ethiopia. SAGE Open, 12(2), 21582440221094592.

· Brown, B. D., Horn, R. S., & King, G. (2018). The effective implementation of professional learning communities. Alabama Journal of Educational Leadership, 5, 53–59.

· Brown, C., & Flood, J. (2020). The three roles of school leaders in maximizing the impact of Professional Learning Networks: A case study from England. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101516.

· Buttram, J. L., & Farley-Ripple, E. N. (2016). The role of principals in professional learning communities. Leadership & Policy in Schools, 15(2), 192–220. doi:10.1080/15700763.2015.1039136

· Darling-Hammond, L., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1995). Policies that support professional development in an era of reform. [electronic version]. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(8).

· Dufour, R., & Eaker, R. (1998). Professional Learning Communities at Work:Best Practices for Enhancing Student Achievement. Solution Tree; ISBN-13: 978-1879639607

· European Commission. (2015). Teaching practices in primary and secondary schools in Europe: Insights from large‐scale assessments in education (JCR Report). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU.

· European Parliament and Council (2001). Recommendation of the European Parliament and Council on European cooperation in quality evaluation in school education, Official Journal of the European Communities (2006/961/EC). Unpublished document.

· European Communities (2008). The European Qualifications Framework. ISBN978-92-79-08474-4.

· Flemming, K., Booth, A., Garside, R., Tunçalp, Ö., & Noyes, J. (2019). Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Global Health, 4(Suppl 1), e000882. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000882

· Johannesson, P. (2020). Development of professional learning communities through action research: Understanding professional learning in practice. Educational Action Research, 30(3)1–16. DOI: 10.1080/09650792.2020.1854100

· Halász, G. (2013). European Union: The strive for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. In Education policy reform trends in G20 members (pp. 267-286). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

· Hayrol Azril Mohamed Shaffril., Asnarulkhadi Abu Samah., Samsul Farid Samsuddin., & Zuraina Ali. (2019). Mirror-mirror on the wall, what climate change adaptation strategies are practiced by the Asian's fishermen of all? Journal of Cleaner Production, 232, 104–117.

· Hord, S. (2009). Educators work together toward a shared purpose–improved student learning. Journal of Staff Development, 30(1), 40–43.

· Hord, S.M. (.1997). Professional learning communities: Communities of continuous inquiry and improvement. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory

· Huffman, J. B., & Hipp, K. K. (2003). Reculturing schools as professional learning communities. Rowman & Littefield.

· Jafar, M. F., Yaakob, M. F. M., Awang, H., Zain, F. M., & Kasim, M. (2022). Disentangling the Toing and Froing of Professional Learning Community Implementation by Reconnecting Educational Policy with School Culture. International Journal of Instruction, 15(2), 307– 328.

· Kalman, A. (2016). The meaning and importance of Thomas Kuhn’s concept of ‘paradigm shift’. How does it apply in Education? Opus et Educatio, 3(2).

· Kalman, A., & Citterio, L. (2020). Complexity as new normality: What is going on? Információs Társadalom: társadalomtudományi folyóirat, 20(2), 19-32.

· King, F., & Holland, E. (2022). A transformative professional learning meta-model to support leadership learning and growth of early career teachers. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2022.2037021

· Little, J. (1982). Norms of collegiality and experimentation: Workplace conditions of school success. American Educational Research Journal, 19(3), 325.

· Meeuwen, P. V., Huijboom, F., Rusman, E., Vermeulen, M., & Imants, J. (2020). Towards a comprehensive and dynamic conceptual framework to research and enact professional learning communities in the context of secondary education. European Journal Of Teacher Education, 43(3), 405–427.

· Oppi, P., & Eisenschmidt, E. (2022). Developing a professional learning community through teacher leadership: A case in one Estonian school. Teaching and Teacher Education: Leadership and Professional Development, 1, 100011.

· Pandian, V., Awang, M. B., Ishak, R. B., & Ariff, N. (2022). A Systematic Literature Review on Professional Learning Community Models. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 7(11), e001902-e001902.

· Saydam, D. (2019). Teachers’ beliefs on professional learning. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 34(4), 915–925.

· Scull, A. (2021). Creating community, learning together: Designing and delivering a program for staff professional development. College & Research Libraries News, 82(3), 117.

· Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221–258. 10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

· Tai, M.K., & Omar Abdull Kareem. (2021). An Analysis On The Implementation Of Professional Learning Communities In Malaysian Secondary Schools. Asian Journal of University Education, 17(1), 192–206. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v17i1.12693

· Toole, J. C., & Louis, K. S. (2002). The role of professional learning communities in international education. In Second international handbook of educational leadership and administration (pp. 245–279). Springer, Dordrecht.

· United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (1990). Human Development Report 1990: Concept and Measurement of Human Development. New York: United Nations Development Programme. http://www.hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr1990

· Vella, R., & Azzopardi, J. A. (2021). Effective Continuing Professional Learning and Development: The Case of Mathematics Teachers in Malta. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research, 40(5), 32570–32580.

· Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

· Yeol, L. S. (2020). Analysis of the effect of school organizational culture and professional learning communities on teacher efficacy. Интеграция образования, 24(2 (99)), 206–217.