Attila MÉSZÁROS – Richárd SZALÓKI

The need and opportunities for developing emotional intelligence in education

Introduction

Emotional intelligence directly influences teacher performance as one of the indicators of successful teaching evaluation. In a comprehensive meta-analysis, Martins, Ramalho, and Morin (2010) showed that emotional intelligence is clearly, firmly, and unequivocally related to mental and physical health. They examined emotional intelligence in school performance. It was shown that emotional intelligence has organizational, clinical, health, educational, and social implications. However, it should not be thought that there are no critical opinions and debates in the field. Many researchers still doubt whether emotional intelligence adds anything to the traditional personality and cognitive ability variables (A., Bastian, & Nettelbeck, 2005). Another question of great interest and importance is whether emotional intelligence can be developed. Recent evidence from Di Fabio and Kenny (2011) suggests that specific training may benefit significantly. We need to know more about what type of training is needed and why (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2011).

Research has suggested that some people are more successful in their careers than others, even when they have equal educational and experiential opportunities (Scheusner, 2002). One explanation may be differences in intellectual intelligence (IQ) and emotional intelligence (EQ). IQ characterizes intellectual competence, or the ability to apply knowledge in making decisions and adapting to new situations. EQ is one formulation of emotional and social competencies or the ability to identify emotional expressions in oneself and others (Goleman, 1997). Although both can be improved with training and can change over time, EQ differs from IQ's ability to respond to emotions to environmental stimuli.

Thus, emotional intelligence is recognizing and regulating emotions in oneself and others to make effective decisions. Emotional intelligence is a relatively new term, but it was already addressed by Plato 2000 years ago when he stated that all learning has an emotional basis (Bollokné Panyik, 1999). Wechsler developed the concept of non-cognitive intelligence, which he argued is essential for success in life, and that intelligence is incomplete until we can define its non-cognitive aspects (Dhani & Tanu, 2016 ). The common denominator of the psychological views on emotional intelligence, which will be presented later, is that we can distinguish at least three skill domains:

• ability to Emotional Awareness, or the ability to identify and name one's own emotions

• the ability to harness emotions and apply them to tasks such as thinking and problem-solving

• the manage emotions, which includes both regulating one's own emotions when necessary and arousing or calming people.

It is thus accepted that emotional intelligence goes beyond the purely cognitive elements, as it also includes elements of the affective domain.

The initial ability-based definitions of emotional intelligence were recorded in the 1990s by Mayer and colleagues. According to them, 'emotional intelligence is a form of emotional information processing that involves the accurate evaluation of one's own emotions and the emotions of others, the appropriate expression of emotion, and the adaptive regulation of emotions in ways that improve the quality of life' (Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P., 1990). In introducing the concept of emotional intelligence, Salovey and Mayer argued for broadening traditional models of intelligence, emphasizing the adaptive values of flexible planning, social competence, and attentiveness to others. Mayer and his colleagues elaborated and extended the original definition a few years later. According to them, emotional intelligence is 'the ability to recognize emotions' meaning and relationships and think and problem-solve based on these. Emotional intelligence plays a role in the perception of emotions, the assimilation of emotions, the understanding of the information carried by emotions, and the management of emotions.' (Sternberg, 2000).

Relational systems of emotional intelligence in education – Educational aspects of empathy

In Hungary, empathy is associated with Béla Buda, whose book Empathy – the art of empathy was published in 1978. As a result of the book, the concept of empathy became an everyday part of not only professional but also intellectual vernacular. Béla Buda defines empathy as 'to empathize is to see with the eyes of another person, to hear with the ears of another person and to feel with the heart of another person.' (Buda, 1985).

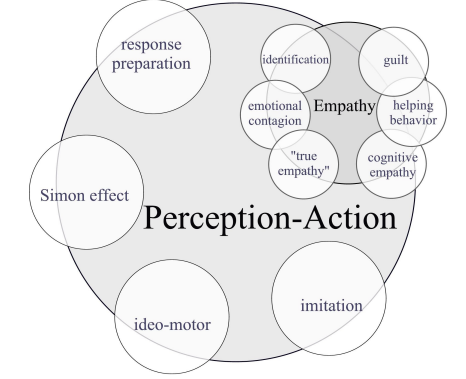

According to Baron Cohen (2004), 'empathy is the impulse to recognize the feelings and thoughts of others and to respond to them with appropriate emotions' (Baron-Cohen, 2004). Carl Rogers wrote in 1959: 'to be empathic is to perceive accurately the interpretive framework of the other with all its emotional meanings and components, as if one were the other, but without ever losing this 'as if". Since Béla Buda's book, much research has been published on empathy development and neurobiological background. There is a consensus in the literature that empathy is a multidimensional concept that includes both affective and cognitive components (Preston, 2002). The affective component refers to empathic caring and concern, while the cognitive component refers to taking a different perspective (Figure 1). In itself, affective empathy may be unpleasant for the empathizer, who may experience distress and anxiety when seeing the other person's negative emotions. Thus, affective empathy without cognitive empathy can cause hypersensitivity and vulnerability. This self-referential distress at seeing another's suffering is called empathic distress, which can come at the expense of empathic caring (Hoffman, 1991).

Figure 1: Perception-action model of empathy

Source https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10866840_Empathy_Its_Ultimate_and_Proximate_Bases(download: 2022.01.06.)

In the early 1990s, the focus of empathy research turned to the possibility of objective measurement, and researchers developed several tests for this purpose. Self-completion tests, which ask about an individual's behavioral habits and sensitivity in social relationships, measure the person's empathic capacity in general, i.e. the degree of dispositional empathy. One such test is Baron-Cohen's empathy quotient test (Baron-Cohen, 2004).

Empathy and emotional intelligence have been measured among mental health undergraduates. 104 university students and their teachers participated in the study. They investigated whether empathy can be taught and whether it is possible to teach a person to 'walk in someone else's shoes.' The measurement was done using the Davis IRI Interpersonal Reactivity Index Scale (Davis, H. M., 1983), using pre-and post-tests. Intervention between the measurements was done with Rogers-based skills training. Teachers provided information about their training and teaching experiences and observed the empathy skills of their students through interviews and questionnaires. As a result of the measurements, it can be shown that the development of empathy, 'teachability,' shows statistical significance in the subscales of empathic caring and perspective-taking. The control group, which did not receive any development, did not show any improvement in any of the subscales, while the group that received training did.

Although the female students had higher empathy skills at the beginning of the measurement, the development showed that the male students' empathy skills could be developed similarly, and the significant differences were reduced, i.e., both genders could be developed equally in empathy. After performing factor analysis, as recommended by Davis, the total empathy factor was not calculated from the results of all four subscales. However, the empathy mean was calculated by excluding personal distress. There was a demonstrable improvement in the empathic concern, perspective shift, and overall empathic mean (sum of the scores of the fantasy scale, empathic concern, and perspective shift subscales). According to Davis, the independent and dependent variables on the separate subscales of empathy cannot be accurately estimated when using the IRI. He further suggests that the personal distress subscale should not be added to the scores of the other subscales because it is the most primitive empathy component. It has been shown that with advancing age, with the onset of true adulthood, i.e., with the maturation of the personality, the empathy component of the personal distress subscale tends to decrease. A further result of the study is that the development of genuine empathy of the personality starts with communication in childhood and the identification with imagined situations and characters in adolescence. The ability to imagine and identify is the starting point for developing empathy. Thus, the development of empathy occurs in stages and a process. It can be demonstrated using the IRI scale. For example, there is an increase in the scores on the fantasy scale in university age groups compared to adolescents. Thus, the empathy skills of university students are more developed, and the basis for this can be detected in the fantasy scale. These can be built upon by more mature empathic components, such as the attitudinal components of perspective-taking cognitive and empathic caring attitudes.

Further findings of the study are that women's empathic communication is better than men's, but the effect of developmental training is based on Carl Rogers' person-centered principles. In other words, if liked, men's empathy skills can be developed similarly. Empathy can be taught regardless of gender. The total empathy potential as an emotional empathy skill, calculated from the scores of the three subscales, was investigated in this research (S., Nadeau, K., & Marz, 1994).

The relationship between emotional intelligence and empathy

Emotional intelligence is a set of human capacities that takes emotional adaptation to the highest level. However, there are at least three basic interpretations of this concept. The broadest interpretation is the cultural level, characterized by how a person with the currently expected abilities relates and adapts to different social groups in a given period. The second interpretation is that emotional intelligence includes personality traits essential for achieving goals, assertiveness, and success, such as perseverance, achievement motivation, social skills, and self-discipline. Finally, according to the third and narrowest interpretation, represented by academic psychology, emotional intelligence is the set of skills that we use when processing emotional information (Oláh, A., 2005).

The separation of the internal components of intelligence has been going on for decades. From its collective concept, creativity is separated, followed by emotional intelligence. Some researchers emphasize the role of emotional and social-relational ability rather than the personal cognitive nature of intelligence. According to Thorndike (1920), such a component is social intelligence, a key element of interpersonal relationships. In his view, it is essential to understand others accurately and to behave accordingly. In Gardner's (1993) multiple intelligence concept, there are also elements of intrapersonal intelligence - self-monitoring and activating ability - and interpersonal intelligence, i.e., the ability to relate (Gardner, 1993).

The best-known of the mixed models of emotional intelligence is that of Bar-On (1997), who argues that 'emotional intelligence is the set of emotional, personal and social competencies and skills that contribute to an individual's ability to cope effectively with the demands of his or her environment.' (Bar-On, 1997). Bar Bar-On draws on Gardner's theory and believes that emotional and social intelligence are closely related trait characteristics that can be understood as components of a common construct, 'emotional and social intelligence' (Bredács, 2009). Dispositional and situational empathy; the relationship of empathy to interpersonal and intrapsychic factors.

Empathy is a subset of emotional intelligence, a concept that is named after Bar-On (Bar-On, 1997). Another way of measuring empathy is to test a person's ability to recognize the emotional reactions of others, i.e., to test situational empathy.

Empathy is an ability that depends on personality: there are people with good and less good empathic skills. It is called dispositional empathy (Davis, H. M., 1983). It does not mean that empathy cannot be developed. Furthermore, empathy depends on the state of the person at the moment. After all, if someone is tired, in pain, or seriously distressed, his or her empathic capacity will be reduced. Anything that focuses a person's attention on him or herself reduces empathy. Thus, empathy is not only a stable personality trait but also depends on the current state of mind. The latter is situational empathy, which always refers to a given moment.

Focusing on the interpersonal aspect of empathy, Davis (1983) also argues that a parallel emotional response may emerge in the recipient due to the affective state of the other, leading to the emergence of emotions similar to the other's actual or assumed emotions.

Already in adolescence, the role of specific characteristics of empathy and anxiety is significant, i.e., their development is decisive for problem-solving, and vice versa: both anxiety and empathy depend on the effectiveness of problem-solving. The relationship between social problem-solving, anxiety, and empathy was investigated in adolescents aged 12-19. The study reveals that the relationship between positive orientation in problem-solving and a cognitive sub-domain of empathy, perspective taking/shifting, gradually strengthens with age. Negative orientation and avoidance or impulsivity show an increasingly close relationship with another component of empathy, personal distress. Negative orientation is strongly influenced by trait anxiety in all age groups. The findings may be helpful in everyday pedagogical practice as well as for formulating future research and development goals (Gáspár & Kasik, 2015).

The Davis IRI distress scale, which measures the tendency to adopt negative emotions, shows a significant positive correlation between emotional exhaustion and a decrease in feelings of personal efficacy. While depersonalization is inversely associated with perspective-taking and empathic caring, the ability to change perspective is predictive of increased feelings of personal efficacy. Feelings of distress are also found to be an influential factor in emotional exhaustion and the reduction of personal efficacy. The three most important variables determining the development of feelings of personal efficacy are perceived distress, the ability to change perspective, and impersonal treatment. It is expected that the decrease in feelings of personal efficacy is most influenced by perceived distress and depersonalization among the variables examined. An increase in personal efficacy is expected with the emergence of the ability to change perspective. Depersonalization is reduced by empathic caring and an attitude that focuses on the healer-patient relationship, but with an increase in emotional exhaustion, depersonalization is expected (Fülöp & Devecsery, 2012).

Empathy provides an essential basis for being able to relate intimately to others and is also vital for coping with stress and managing conflict adequately (Kremer & Dietzen, 1991).

Empathy is critical to a person's self-efficacy, alongside equally important perceptions of reality, intelligence, and creativity. It has essential preventive potential in maintaining mental health (S., Nadeau, K., & Marz, 1994).

The relationship between emotional intelligence and coping strategies

Coping skills, also known as coping strategies, measure how an observed person copes with stressful situations. Behavioral science argues that the human-environment system dynamically shapes a person's behavior (Kopp, 1994). In this system, the decision-making process plays a key role. The person must constantly decide whether he or she can meet the given environmental challenges and find solutions. In short, to cope with the situation. Coping strategies are also crucial because lifelong learning requires them (Molnár, 2015).

According to the human-environment model, the person strives to maintain a state of equilibrium. Stress, in this case, can cause a person to lose mental balance. Coping is a process whereby a person makes cognitive and behavioral efforts to resolve the conflict that is the source of stress.

Lazarus and Launier (1978) distinguish two types of coping (Margitics & Pauwlik, 2006):

• Problem-focused coping is when the person focuses on the situation, and the problem, in an attempt to change it so that it can be avoided in the future.

• Emotion-focused coping: the person is then concerned with alleviating the emotional reactions caused by the stressful situation, preventing negative emotions from taking over. The person uses it even if the situation cannot be changed.

Problem-focused coping involves using problem-solving strategies, which can be directed outwards, at the problem situation itself, and inwards, with the person changing something in themselves rather than changing the environment.

As a result of Lazarus and Folkman's (1986) research, a further eight types of strategies can be distinguished within problem-focused and emotion-focused coping (Margitics & Pauwlik, 2006):

• Confrontation: This involves confronting the problem, actively coping;

• disengagement: it means distancing oneself emotionally and mentally from the situation in order to gain energy for further coping;

• regulating emotions and behaviour: this means finding the emotional expression and behaviour that best helps to resolve the situation;

• seeking peer support: this means seeking and using the resources and support available in the peer environment;

• taking responsibility: this involves taking perceived, attributed control;

• Problem-solving planning: a specifically cognitive, rational strategy it involves evaluating the options that may help to resolve the situation;

• avoidance-avoidance: not engaging in confrontation, exiting the situation;

• seeking positive meaning: evaluating the event with negative meaning as a challenge in a positive way.

According to Attila Oláh's international research, adolescents growing up in all the cultures he has studied (Hungarian, Indian, Italian, Swedish, Yemeni) have adopted constructive ways of coping with low and medium anxiety, and avoidance as a maladaptive way of coping with tension in high anxiety (Oláh, 1995).

The need to develop emotional intelligence in education

It is crucial to understand the distinguishing characteristics between emotions and EQ. Emotion is a natural instinctual state from our present and past experiences and situations. Emotions come from our environment, our circumstances and knowledge, as well as our moods and relationships. Our feelings and experiences influence our emotions. In contrast, EQ is the ability, skill, and Awareness to know, recognize and understand these feelings, moods, and emotions and positively use them. EQ is learning to manage emotions and use that information to behave and act, including making decisions, solving problems, self-management, and leading others. Furthermore, EQ can be confirmed to enhance self-esteem, well-being, and professional and personal motivation (Faltas, 2017).

People are often surprised that there are three different theories within the emotional intelligence paradigm. Each of these theories attempts to better understand and explain the skills, traits, and abilities associated with social and emotional intelligence. The existence of multiple theoretical perspectives within the emotional intelligence paradigm does not indicate weakness but rather shows the magnitude of the field. Thus, the definitions within the field of emotional intelligence are variable, complementing rather than contradicting each other.

However, despite its importance in schooling, there is still not enough emphasis on developing emotions. According to a US study, half of the 150 teachers surveyed had never heard of emotional intelligence. Most of those familiar with the concept understood it as 'an important life skill' or 'something that makes learning more effective and promotes well-being.' On the other hand, a third of teachers considered it to be 'interesting but confusing,' while some saw it as a new kind of sentimental fad' (Claxton, 2005).

A 2019 study suggests that years in education influence the emotional intelligence of teachers and trainers. The results confirm a significant difference in emotional intelligence between students in full-time education and trainers in teacher education. The factors expressing empathy are higher for instructors already in their careers. Practice and age also play a significant role in this. This variation is two-way. Students have significantly higher fantasy scale scores, i.e., a tendency to identify with fictional persons. Because of their less experience, they find it easier to place themselves in an imaginary situation. Therefore, they are more congruent with the student's ideas and more involved. Teachers in the field are more detached when it comes to events that require imagination. The values of personal distress are also higher for students than career educators, making it more difficult for them to respond adequately to a stressful situation. In other words, they are more robust in the affective involvement factor of empathy, which makes the student experience the suffering and anger of others more acutely. As a result, they become more involved more quickly.

On the other hand, this emotional component can also inhibit empathic caring, which is a core task of the teacher. Practitioners' perspective-taking capacity increases so that with this cognitive component of empathy, they can better take up a point of view or change focus, which can be accomplished in a mental operation during an affective engagement. The other strength that was significantly different was empathic caring. The ability to empathize was higher for the trainers in the field than for the students, so an affective impact could more easily induce action in them.

In addition, the research found a correlation between intrapersonal (confidence, self-awareness, self-esteem, independence, self-actualization) characteristics and self-punishment as a coping strategy. It means that if a trainer, educator, or developer has good self-awareness, they will put themselves in the right place when faced with a problem. So they try to maintain the stability of their personality when dealing with difficult or stressful situations, so the focus shifts from the threat to the self. Therefore, they often seek external support and help in stressful situations. In turn, the intrapersonal scale and the distraction coping strategy were also correlated with each other for trainers in the labor market, so one possible manifestation of their coping is that the individual performs an avoidance maneuver, exits the situation, delays intervention, turns towards self (Mészáros, 2019).

When examining the coping strategies of each group, the research indicated that students had significantly lower stress control scores than those in the teaching profession. So maintaining their stability requires much more effort. On the other hand, teachers are more confident and flexible. They have the ego power to maintain their stability. As a result, teachers can identify and use the two steps of the coping process more efficiently. The first step is to clarify the extent to which stress is affecting the individual's life and goals and whether and what can be done to eliminate the stressor. In the second step, it takes into account what internal resources are available for coping (whether a problem-centered or emotion-regulating strategy is needed, what would happen if nothing were done about the situation) and, if these are exhausted, it changes its internal attitude and itself (Mészáros, 2019).

One of the pillars of emotional intelligence development is self-awareness, i.e., knowing one's own emotions, desires, and motivations and managing them in the present situation to face a positive future. The more success we have, the more effectively we will experience the self-control, self-mastery, and self-direction that will help us to cope successfully in all areas of life. This combination of skills makes it easier to recognize, manage and cope with stressful situations and conflict and to regulate emotions so that they are balanced and negative emotions do not dominate, enabling us to perform well under pressure. This attitude will be the basis for successful cooperation with others, good conflict management, and successful relationship building (Balázs, 2014).

Can emotional intelligence be developed in education?

A lot of research has been done to understand how theoretical constructs work. In this sense, it is crucial to develop appropriate measurement tools to guide and interpret the study correctly (e.g. (Baron & Parker, 2000); (Petrides & Furnham, 2001)).

A further factor in the theory of emotional intelligence is the assumption that, unlike IQ, emotional intelligence can be developed. However, there is no convincing empirical research suggesting that these skills can be improved and learned.

Bar-On found that older age groups tend to score higher on the EQ scale, suggesting that, to some extent, EQ can be learned through life experience. There are several findings in psychotherapy; training programs demonstrate that people can improve their emotional competencies through strenuous effort and systematic programs. Furthermore, recent findings in the field of emotional neuroscience have shown that emotional brain connections show remarkable plasticity in adulthood (Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000).

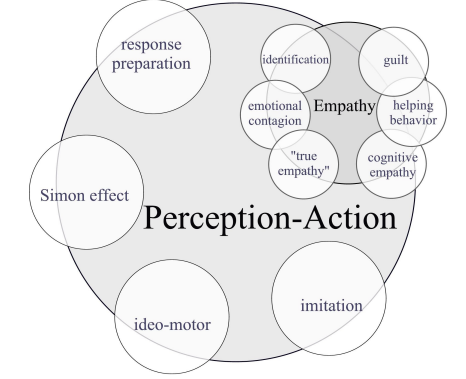

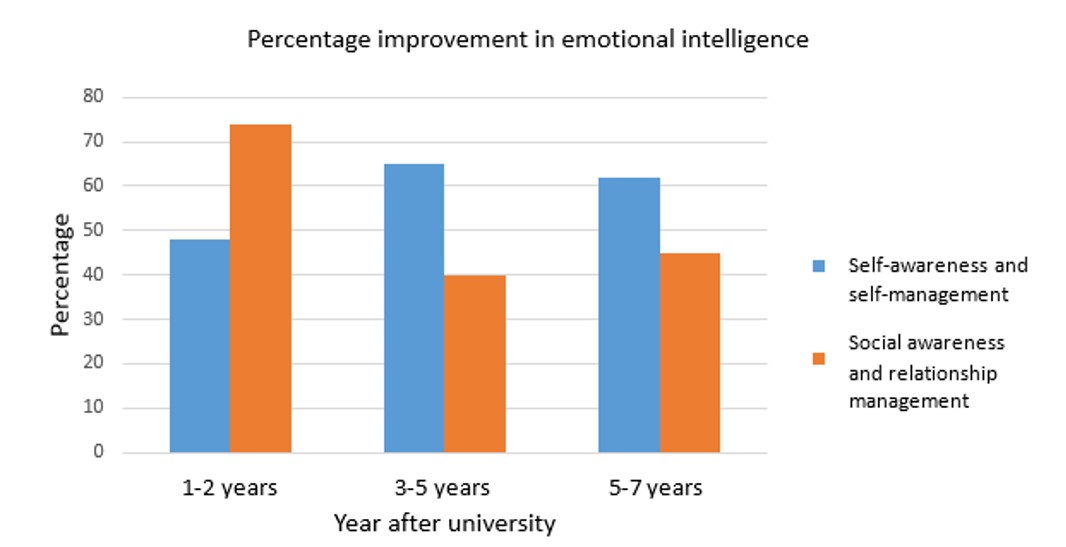

Although research on emotional intelligence competencies stands out, a longitudinal study was conducted at the Weatherhead School of Management at Case Western Reserve University (Boyatzis, Cowan, & Kolb, 1995). Students in the study participated in a competency-building course that allowed them to develop their emotional intelligence and cognitive skills. Individual goals and an individualized learning pathway were developed and implemented. Students were objectively assessed at the beginning of the program, after graduation, and years later in the workplace. The research results show that their emotional intelligence competencies improved significantly and became sustainable over time. The fact that the effects observed in the experiment were sustained over several years is evidence that not only is it possible to improve emotional intelligence competencies but that such changes can be sustained over time (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Longitudinal study of Western Reserve University

Source: (Boyatzis, Cowan, & Kolb, 1995)

Affective neuroscience findings also support the potential for developing emotional intelligence. For example, LeDoux's findings show that although there are stable individual differences in the central relations of individual emotions, plasticity in activation patterns can also be observed (LeDoux, 1996).

In current practice, however, traditional training at university is performance-based. Therefore, the use of non-traditional pedagogical methods focusing on the development of emotional intelligence is rare. Therefore, there is a need for training programs that promote self-efficacy, the development of a personal vision, and the development of emotional intelligence competencies. If this development takes place, it could give the graduate student a significant advantage in the labor market (Csikszentmihályi, 1990).

Why will people with higher EQ be more successful?

Success in employment, including teaching, is critical. Both our success and the success of our graduate students. So, increasing emotional intelligence can influence the success and quality of teachers' work. When comparing employees, we can see that people with higher emotional intelligence are characterized by: (Furnham, 2012)

• people with high EQ communicate their ideas, intentions, and goals better.

• EQ is closely linked to social skills for teamwork, which are very important at work.

• People with higher EQ build a supportive environment that increases organisational commitment.

• People with high EQ perceive and know their own and their peers' strengths and weaknesses, which enables them to exploit the former and compensate for the latter.

• Higher EQ is associated with more effective adaptive skills, which enable people to better manage expectations and stress.

• People with a high EQ can accurately identify feelings and needs and are more motivated and supportive. They generate more excitement, enthusiasm, and optimism.

Example of developing emotional intelligence in pre-primary education

The University of San Francisco's teacher education department introduced a course on emotional intelligence for students. The course consisted of several components, among which the most interesting parts were the exercises designing new pedagogical environments and methodologies based on theoretical knowledge. In addition, the course included the exploration and use of emotional intelligence theories in teaching and learning. (https://www.usfca.edu/education (download: 2022.01.06.))

Development topics and methods:

• Sessions 1-7: Review of emotional intelligence and creativity theories. (The module consisted of readings, forums, case studies, and assignments.) Assignments included a literature review, pedagogical relevance research, and project group brainstorming on how to incorporate intelligence theories into education through a project. After the presentations, feedback circles were used to help clarify each other's projects.

• From session 7, the project design process followed. The topics of completed projects were: using ice-breaking exercises in teaching, displaying social-emotional information in the classroom, developing self-awareness and empathy, identifying and managing emotions, and managing anxiety in the classroom. The project will develop lesson plans and outlines for these topics, which will be transformed into web-based learning aids for teachers, students, and parents. Short descriptions and presentations have been produced for the online interface. Then the whole thing was tested.

• In the end, everyone had to submit complex project documentation.

The central aim was to create a positive emotional environment for the students through a creative project. The students integrated the development of emotional intelligence in different subjects requiring cognitive skills (music, physical education, geography, biology, mathematics, and economics). In each subject, they wanted to demonstrate the possibility of atypical thinking. The aim was to reduce students' emotional anxiety in the classroom.

The development of emotional intelligence is a critical factor in education. The course presented was successful in motivating teacher candidates to apply emotional intelligence theory in practice. The methods used to develop emotional intelligence also proved to be pedagogically valuable. Positive learning experiences emerged, students began to use new expressive teaching gestures, and a culture of collegiality was promoted. The results of the course suggest that the development of emotional intelligence needs to be introduced into teacher education to enhance the methodological diversity of knowledge and skills for student development, especially for emotional development, and to promote emotional Awareness (Kaplan, 2019).

Summary

Emotional intelligence can be learned. From birth, children can decode the feelings of others, express their emotional states, to delay or even control their emotions, i.e., they learn to 'manage their emotions' (Kádár, A., 2012). Therefore, it is essential to emphasize the development of emotional intelligence in teacher training institutions and teacher training. This development is necessary for two reasons. On the one hand, as our research has shown, the number of teachers who become emotionally frail increases in proportion to their time in the profession, putting their mental health and that of their students at risk. On the other hand, their relational skills suggest that the majority of these teachers are capable of effective interpersonal relationships, as they are well-meaning, willing to care for others, and even their strong desire to conform is underpinned by a desire to maintain good social relationships (Baracsi, 2011).

The family is the primary setting for EQ development; from early childhood, a parental attitude that allows for mistakes within certain limits is essential. Just as a parent can own up to his or her feelings and make mistakes, the child should be given the same opportunity. 'Dare to feel' is also an important motto. One of the foundations of EQ is to be brave enough to be myself and to dare to talk about my feelings! However, in many families this is not the case, weakness is often covered up, the principle of 'the parent cannot make mistakes' is followed, so EQ development also becomes the task of teachers and educators. This is why an integrative development process in this direction is important because the child is given a new chance to change.

EQ is a highly complex system of the affective domain of the human psyche. It is our psychological 'fingerprint', which also has a unique, unrepeatable quality. Three important basic factors can be identified. The first is the way in which a person is emotionally connected to himself and his belief system, which we might call 'self-awareness.' The second is how he or she relates to others, through which he or she acquires 'self-knowledge.' The third is how his emotional experiences are integrated into his personality, i.e., how they affect his behavior in later life in terms of stimulation and inhibition. It is also essential to consider how the emotional consequences of crises and traumas later shape emotional intelligence. For these reasons, it is also crucial that in early childhood, when one enters the school system, one is exposed to an adult whose emotional intelligence is high and whose personality has been transformed. As the average age of the teaching profession is high, Hungary needs all newly qualified teachers. Thus, it does not matter what EQ scores students come out of the faculty with. Research has shown that with age and practice, EQ scores increase, but until then, we are influencing many children. It would be good if students came out of universities with higher EQ scores. This would also positively impact child education and, of course, the teacher's professional competencies and interpersonal and intra-psychic skills.

The intervention has also demonstrated that there is potential to develop the EQ area of the person, but that personality development takes a long time and cannot be learned as a cognitive skills-based subject. In his 1997 book, Goleman argued that cognitive ability (i.e., intelligence) contributed about 20% to life success but that the remaining 80% was directly attributable to emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1997). So, it is also helpful to develop EQ in terms of cognitive performance. Thus, the development of emotional intelligence early on, while still in school, has beneficial effects on personality development.

References

· A., V., Bastian, N., & Nettelbeck, R. (2005, October). Emotional intelligence predicts life skills, but not as well as personality and cognitive abilities. Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 39, Issue 6, 1135-1145.

· Balázs, L. (2014). Érzelmi intelligencia a szervezetben és a képzésben. Miskolc: Z-press Kiadó Kft.

· Baracsi, Á. (2011). Pedagógusok érzelmi intelligenciája. In J. Karlovitz, & J. Torgyik, Vzdelávanie, výskum a metodológia. Retrieved from http://www.irisro.org/pedagogia2013januar/0511BaracsiAgnes.pdf

· Bar-On, R. (1997). Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): Technical manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

· Bar-On, R., & Parker, J. (2000). Handbook of emotional intelligence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

· Baron-Cohen, W. S. (2004). The Empathy Quotient: An Investigation of Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and Normal Sex Differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 163-175. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304424998_The_Empathy_Quotient_An_Investigation_of_Adults_with_Asperger_Syndrome_or_High_Functioning_Autism_and_Normal_Sex_Differences

· Bollokné Panyik, I. (1999). Gyermeknevelés – Pedagógusképzés. Budapest: Trezor Kiadó.

· Boyatzis, R. E., Cowan, S. S., & Kolb, D. A. (1995). Innovations in professional education: Steps on a journey to learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

· Bredács, A. (2009). Az érzelmi intelligencia és fejlesztése az iskolában – különös tekintettel a tehetséggondozásra. Iskolakultúra. Retrieved from http://real.mtak.hu/58104/1/17_EPA00011_iskolakultura_2009-5-6.pdf

· Buda, B. (1985). Az empátia – a beleélés lélektana. Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó.

· Claxton, G. (2005). An intelligent look at Emotional Intelligence. London: The Assotiation of Teachers and Lecturers.

· Csikszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó Zrt.

· Davidson, R., Jackson, D. C., & Kalin, N. H. (2000). Emotion, plasticity, context and regulation: Perspectives from affective neuroscience. Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 890-909.

· Davis, H. M. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 44 No. 6., 113-126. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/215605832_Measuring_individual_differences_in_empathy_Evidence_for_a_multidimensional_approach

· Dhani, P., & Tanu, S. (2016). Emotional intelligence; history, models and measures. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305815636

· Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, A. (2011). Promoting Emotional Intelligence and Career Decision Making Among Italian High School Students. Journal of Career Assessment 19 (1),, 21-34.

· Faltas, I. (2017, 03. 04). Three Models of Emotional Intelligence. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314213508

· Furnham, A. (2012, February). Emotional Intelligence. Retrieved from researchgate.net: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221923485

· Fülöp, E., & Devecsery, Á. C. (2012). Az érzelmi bevonódás és a kiégés összefüggései pszichiáter rezidensek körében. Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika, 13 (2012) 2, 201-217. Retrieved from http://real.mtak.hu/58159/1/mental.13.2012.2.6.pdf

· Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences. The theory in practice. New York: BasicBooks.

· Gáspár, C., & Kasik, L. (2015). A szociálisprobléma-megoldás, az empátia és a szorongás kapcsolata serdülők körében. Iskolakultúra, (25. évfolyam, 2015/10. szám). Retrieved from http://real.mtak.hu/34834/1/05.pdf

· Goleman, D. (1997). Érzelmi intelligencia. Budapest: Háttér Kiadó.

· Hoffman, I. (1991). Empátia, társas kogníció és morális cselekvés. In K. Zs.(szerk.): Morális fejlődés, empátia és altruizmus. Szöveggűjtemény. (pp. 43-71). Budapest: Eötvös Kiadó.

· Kádár, A. (2012). Az érzelmi intelligencia fejlődése és fejlesztésének lehetőségei óvodás- és kisiskoláskorban. PedActa, Volume 2, Number 1.

· Kaplan, D. E. (2019). Emotional Intelligence in Instructional Design and Education Psychology, 10, 132-139. Psychology, 2019, 10, 132-139. Retrieved from https://file.scirp.org/pdf/PSYCH_2019013116182894.pdf

· Kopp, M. (1994). Orvosi pszichológia. Budapest: SOTE Magatartástudományi Intézet.

· Kremer, J. F., & Dietzen, L. L. (1991). Two approaches to teaching accurate empathy to undergraduates: Teacher-intensive and self-directed. Journal of College Student Development, 69-75.

· LeDoux, J. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Simon and Schuster.

· Margitics, F., & Pauwlik, Z. (2006). Megküzdési stratégiák preferenciájának összefüggése az észlelt szülői nevelői hatásokkal. Magyar Pedagógia, 106. évf. 1. szám, 43–62.

· Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. (1990). “Emotional intelligence”. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 185-211.

· Mészáros, A. (2019). Az érzelmi intelligencia és megküzdési stratégiák vizsgálata pedagógus hallgatók körében. Pszichológia MA diplomamunka. Kolozsvár: BBTE.

· Molnár, G. (2015). Lifelong learning stratégia szerepe az oktatási és képzési rendszerben Magyarországon. In T. Judit, Százarcú pedagógia (pp. 403-409). Komárno: International Research Institute.

· Oláh, A. (1995). Coping strategies among adolescents: A cross cultural study. Journal of Adolescence, 18./4, 491–512.

· Oláh, A. (2005). Érzelmek, megküzdés és optimális élmény. Belső világunk megismerésének módszerei. Budapest: Trefort Kiadó.

· Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait Emotional Intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Psychology, 425-448. Retrieved from http://www.psychometriclab.com/adminsdata/files/EJP%20(2001)%20-%20T_EI.pdf

· Preston, S. d. (2002). Empathy: its ultimate and proximate bases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

· S., H. L., Nadeau, M. S., K., W. L., & Marz, K. (1994). The teaching of empathy for high school and college students: Testing Rogerian methods with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Adolescence, 29(116):961-74. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/15306035_The_teaching_of_empathy_for_high_school_and_college_students_Testing_Rogerian_methods_with_the_Interpersonal_Reactivity_Index

· Scheusner, H. (2002). Emotional Intelligence Among Leaders and Non-Leaders in Campus Organizations. Retrieved from https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/32134

· Sternberg, R. (2000). “Models of Emotional Intelligence”. In M. J.D., P. Salovey, & D. R. Caruso, Handbook of Intelligence. England: Cambridge University Press.