Brian NOLAN

On the complicated relationship between (Irish) culture and language

In this paper we examine the nature of the relationship between culture and language, and its complexity, and how culture informs language usage. Our cultural sense entails our knowledge about cultural norms, beliefs and values of human society, a community, and our generalised knowledge about the language system that we use in our social and communicative interactions. Therefore, our cultural knowledge includes ontology, representation, reasoning, cultural schemata, cultural metaphors and cultural conceptualisations. Many artists (painters and poets) use language in the service of their art, and visual artists frequently use text directly in paintings as a cultural visual-linguistic semiotic.

The hypothesis in this research study is that meaning in culture is facilitated by language and that language draws on cultural common ground while the cognitive processes that retrieve a meaning from language use are argues to be those characterised within Relevance Theory. Additionally, we argue that these cognitive processes also apply to retrieving meaning from art, music, poetry, and artefacts within the linguistic landscape.

The organisation of this paper is as follows. First, we discuss the difference between culture and civilisation, while highlighting the constituents of culture. We follow this with an overview of the relationship between culture, worldview and introduce the idea of common ground[1] as an important consideration. Then, we look at the application of language in the service of culture, taking in the way that artists employ language in their work. Then we look at how meaning is retrieved from art and language. Several examples are provided from poetry, the Irish cultural narrative and linguistic landscape, that reinforce the necessity of a rich shared common ground. Our conclusions will draw together several threads to relate culture, common ground, language and the cognitive operations that deliver a relevant meaning.[2] To provide evidence to support this hypothesis, we examine next the questions of what is culture, and is culture different to civilisation?

Civilisation is considered to be all of human society with its well-developed social organisations, including the culture and way of life of a society at a particular period in time. Civilisation is therefore the condition that exists when people have developed effective ways of organising a society and care about art, science, and such like - it’s the social process whereby societies achieve an advanced stage of development and organisation. Clearly, there is some overlap between culture and civilisation and it would be useful to define culture before we start our exploration.

The notion of what constitutes ‘CULTURE’ is slippery and tricky. It probably has at least four major senses and, as such, can mean (1):

(1) The constituents of culture

|

A body of artistic and intellectual work

|

artefact

|

|

A means of spiritual and intellectual development

|

language

|

|

The values, customs, beliefs and symbolic practices by which people live as a community

|

worldview

|

|

A whole way of life viewed at some moment in time

|

lifestyle

|

‘Irish culture’, for example, can mean the poetry, music and dance of the people who inhabit the island of Ireland; or it can include the kind of food they eat, the sort of sports they play and the type of belief systems they practise.

The poet T.S. Eliot[3], in his 1973 book, Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, took culture to include ‘all the characteristic activities and interests of a people’. We might say that civilisation is to do with organisation of, and facts within, a society, while culture is to do with the values of a society. Civilisation, then, is the precondition of culture, and refers to a world that is manufactured, fabricated and built by people working together. Language, as a means of communication, is essential to this. I now want to discuss culture in relation to cultural common ground and language.

Culture is a kind of social-collective-cognitive background in which we wrap all our beliefs, instincts, prejudices, sentiments, opinions and assumptions. Embedded within a culture is a worldview, and every language gives voice to the distinctive worldview of a specific people. A worldview is a theory of the world, used for living in the world. Our worldview is a mental model of our reality — a framework of ideas and attitudes about the world, ourselves, and of life. Is a worldview important? Yes, of course it is. We might compare the worldview of Europeans of 100+ years ago to that of Europeans today. Of course, it is clear that much has changed in the worldview of people.

There is a rich diversity of cultures (and languages) in our world and a culture is at its finest when language successfully articulates and reflects on the common popular experience of the lives of those in the community. In this way, language and culture distil the intrinsic nature, character and essence of a people. What is shared in a community of speakers within a culture? Cultural knowledge residing in artefacts, language, worldview and lifestyle is shared. Cultural common ground provides the glue between language and worldview. Culture reflects the shared common ground for members of the same community and reflects the repository of our shared knowledge. As a living thing, culture is always a work in progress. In this view, common ground (Table 1) acts as a kind of decentralised knowledge system supporting the cognitive activation of a subset of relevant contextual knowledge.

The types of knowledge[4] characterised in common ground relate to declarative, procedural, heuristic, meta and structural knowledge, and cultural knowledge, along a scale from volatile and dynamic to less-volatile and less-dynamic.

Specifically, we argue that common ground contains relevant knowledge on local dialogue, language, environment, recent events, historical knowledge, common sense, cultural knowledge.

Table 1. Tentative structure of common ground

|

Structure of common ground

|

Contains

|

Volatility / Dynamicity

|

|

|

|

|

|

Local dialogue

|

· Salient events and references within the dialogue chain

|

More volatile / dynamic

|

|

Language

|

· Knowledge of the linguistic system

|

|

|

Environment

|

· Shared knowledge of the entities, actions and context of the local environment and which may prove relevant to the interlocutors within the dialogue.

· Meta and structural knowledge

· Knowledge structures within our overall mental models

· Schemata and frames

|

|

|

Recent events

|

· Shared knowledge of the entities, actions in the context of the local environment.

· Declarative knowledge of concepts and facts

|

|

|

Historical knowledge

|

· Shared cultural knowledge of (recent past to far past) historical context and associated entities, actions and consequences.

· Declarative knowledge of concepts and facts

|

|

|

Common sense

|

· General ontological knowledge about the world, its entities and events.

· Heuristic and experiential knowledge.

· Schemata (Event, Role, Image, and Proposition)

· Frames

|

|

|

Cultural knowledge

|

· Ways of doing things in our community,

· Ways of behaving in our society,

· Common belief sets,

· Cultural values,

· Shared perspectives

· Schemata and frames

· Shared worldview

|

Tending to be non-volatile / non-dynamic

|

What about language? Language is a tool with wide ranging utility and purpose, with function and form developed and refined by humans to satisfy their social need for meaning in the world and within community. The things in the world, entities and actions, are reflected in language and language allows us to communicate regardingthecollection of 'things' of interest to a speech community. In fact, language represents our greatest display of human cognitive power. It is the basis for mathematics, science, philosophy, art, music, and literature. All human languages exist to solve the human problems relating to communication and social cohesion.

How then might we usefully define language? A good definition is provided by Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary (2).

(2) Definition of language

|

Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary[5] defines language as ‘a systematic means of communicating ideas or feelings by the use of conventionalised signs, sounds, gestures, or marks having understood meanings.’

|

Language is crucial for making sense of the world. In particular, we use language for categorising and classifying the components of the world around us. This involves cognition and conceptualisation. As humans, we have evolved to create and store concepts through signs and to recognise relationships between the signs we create. A sign maps form with meaning. Each culture determines which conceptualisations[6], categorisations and cultural generalisations are the most important to it, and the vocabulary and grammar of the languages spoken within that community reflect its priorities of knowledge. A language, therefore, is a repository of the riches of highly specialised cultural experiences.

Language in interaction is fundamentally a cultural activity and, at the same time, language is a tool is instrument for organising our cultural domains. Functionalist linguistics, is a group of approaches to the characterisation of language that understands language structure as reflecting language use within a community of speakers and as such, is sensitive to culture. Functionalist linguists[7] view language as a communicative tool used to relate our experiences and mental representations to the external world. Language is used to maintain cultural conceptualisations through time whereby people use the narrative of oral traditions to connect people, place, history, and culture.

Cultural artefacts such as painting, rituals, language and gesture are all instantiations of cultural conceptualisations and, as such, have a cognitive dimension. The points of intersection between culture, cognition and language all relate to common ground and are therefore concerned with the nature of cognition within the community group. In this regard, common ground acts as a kind of decentralised knowledge system supporting distributed cognition within a community supporting speech acts.

Additionally, it has been argued that the emergence, transmission and perpetuation of cultural conceptualisations are phenomena best understood as constituting a complex adaptive system. Understood as a complex adaptive system, both language and culture can be conceptualised as forming a complex intertwined nexus while allowing us to appreciate the structural connections between them.

Functionalist-cognitive approaches to linguistics, sensitive to the cultural connection, equate cultural cognition with socially situated activity mediated by language.

Nothing has more to tell us about what it means to be human than the forms and uses to which we put language. Languages are central to our achievements in art, science, and gives us access to all the knowledge and skills learned by humans. We have, in a cultural community, the shared knowledge of that community (the shared common ground) organised through language. In this sense, culture is at the interface of knowledge and language. We find examples of this readily in the arts and in poetry.

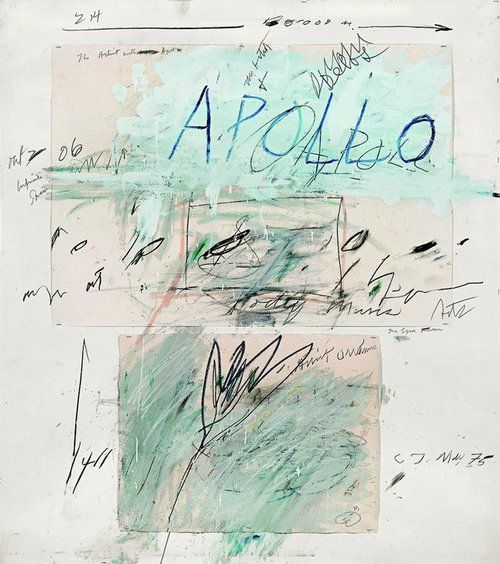

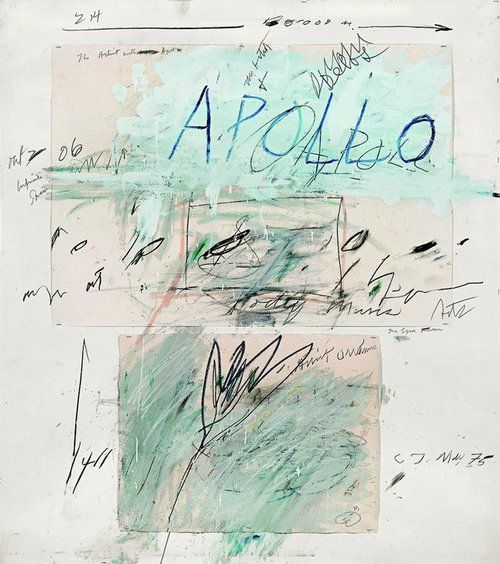

Taking two examples from the visual arts, the globally known artists Cy Twombly (Figure 1) and Jean-Michel Basquiat (Figure 2). Twombly often quoted the poets Stéphane Mallarmé,Rainer Maria Rilke,John Keats, as well as many classical myths and allegories in his works.

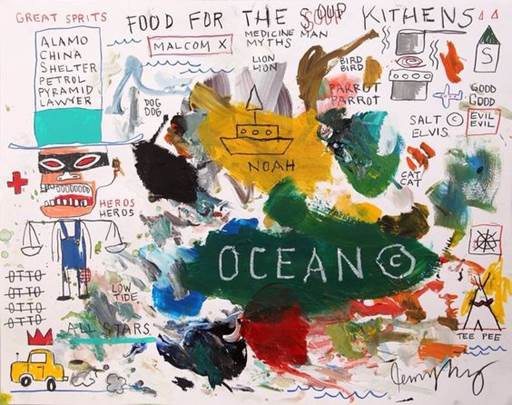

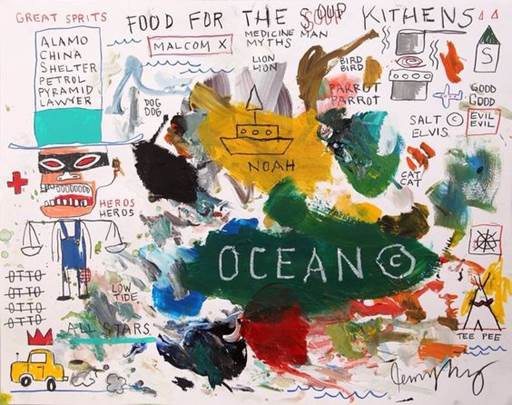

In contrast to Cy Twombly, Jean-Michel Basquiat's art focused on elements of contemporary culture and civilisation. In his painting, Basquiat appropriated poetry, drawing, and painting, and conflated text and image, abstraction, and figuration, with various kinds of textual information mixed freely in his work. In this way, Basquiat used textual commentary in his paintings to better understand deeper truths about the individual, as well as society and its culture.

Figure 1. Cy Twombly painting – Apollo[8]

Figure 2. Basquiat painting – Ocean[9]

There are several ways in which visual artists use words or text in visual art. Words can be used explicitly[10] when they are included in, or on, the visual artwork – we have seen examples of this in Figures 1 and 2. We are all familiar with this explicit use of words within medieval art where the words assume a core prominent position. In particular, medieval illuminated manuscripts (Figure 3) are a key example of an art form that relies on the cohesive interdependence of graphics and language where words and image contribute equally to the overall reading.

Figure 3. The Book of Kells, folio 292r with the text that opens theGospel of John[11]

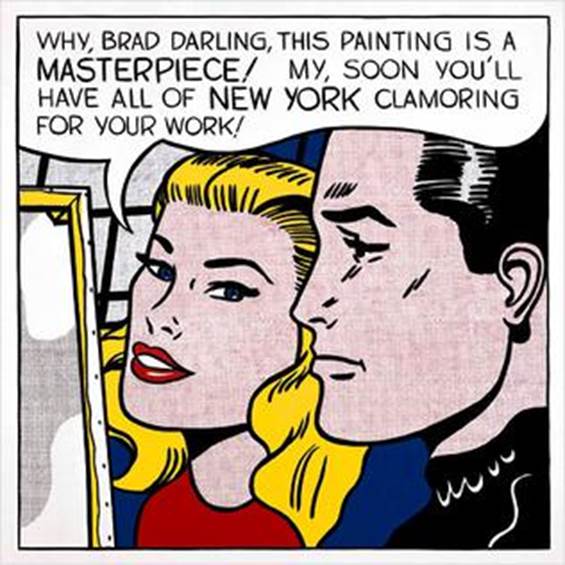

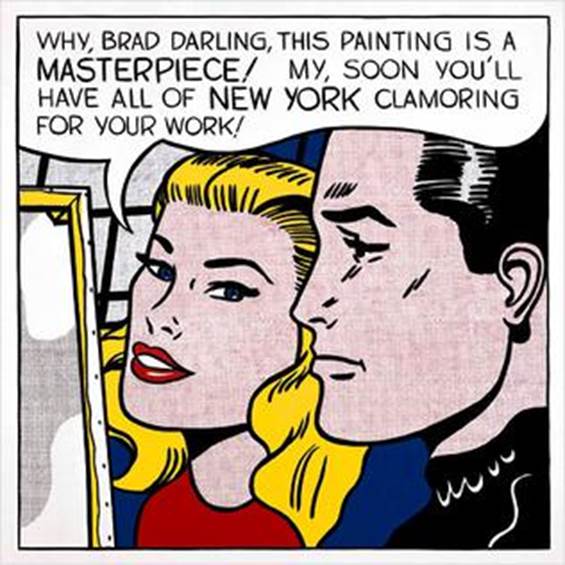

In visual art forms, the explicit words are easily recognised, and are widely accepted while generally understood in virtue of the contribution they make. Indeed, as a more contemporary example, we can consider pop art (Figure 4), modern cartoons, and memes[12] where words are used as a visual semiotic linguistic device that has a cohesive interdependence with the images displayed.

Figure 4. The painting Masterpiece by the American artist Roy Lichtenstein[13]

The word can also appear Implicitly within a supplementary role, (Figure 5) collaborative with the visual form, when they are added to supplement the visual component of a work in some way. The artist’s intention is important here and it seems that, by the design of the artist, implicit words are more elusive.

Figure 5. ‘My Studio’ - painting by Robert Ballagh[14]

The painting by the Irish artist Robert Ballagh is a Pop Art version of Delacroix’s Liberty at the Barricades. The studio setting is symbolised by the inclusion of various art materials. There are several interesting uses of symbols and text in this painting. The newspaper mentioned in this painting as supplementary text is the ‘Irish Independent’ and the name of the city of Derry alludes to the struggles for freedom and civil rights that lead to civil conflict in 1969 and the declaration of Free Derry. The image of the painting Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix is shown (embedded in the painting as a postcard image) to ground the reference for the viewer. The central image of the painting is that of Liberty Leading the People, but in a contemporary Irish context.

The flag in the painting is not the French tricolour but, instead, is the Starry Plough of the Irish Socialist movement. TheStarry Ploughflag was originally used in 1914 by theIrish Citizen Army, a socialistIrish republicanmovement of that time, and was subsequently adopted as the emblem of the Irish Labour movement. The use of the flag here signals that this a people’s struggle for basic rights under an oppressive regime. Here, the artist’s intention is that visual works with words in a supplementary role require the viewer of the art to formulate in their own words, for themselves, what is depicted, notwithstanding the level of abstraction (or not) in the art work.

In instances with these implicit usages, the verbal component supplements the visual to complete the underspecified communication such that the viewer, through a series of cognitive operations, retrieves a meaning from the work. We will come back to these cognitive operations shortly and will introduce the ways in which these function, as characterised by Relevance Theory for linguistic pragmatics, to make some connections and correspondences there between art and text.

Words may intentionally have a high degree of cohesive interdependence such that it is difficult to discern between explicit and implicit usage. In this category of word use within the art, the use of language with the visual component is deeply connected as a direct element of the artists strategy for communication within the overall art work. If we reflect for a moment about this use of language with art, we can recognise that we are actually quite used to words added to art, albeit in a variety of ways. We find these words, for example, in the titles given to paintings (Figure 6) and art objects, and on the captions of the work on the gallery wall, or in art books and catalogues. In this painting, the artist renders a pop art version of the Delacroix work Liberty Leading the People but the French tricolour is replaced by the red flag of Socialism.

Figure 6. ‘Liberty on the Barricades after Delacroix’ – painting by Robert Ballagh[15]

The titles of paintings are usually created by the artist and with the intention of guiding the receptive viewer in the experience of the visual image, that is, in cognitively retrieving a meaning from the work. We can safely assume that paintings depend on this use of words to complement the human instinct to search for meaning in communicative works and that title is considered as having appropriate relevance to aid the art work’s interpretation. The text guides the viewer’s flow of thought through interpretation of the work, along with the viewing of the brush strokes, structural geometry and colour. In the absence of a title to a work – its verbal complement, we typically question whether a visual work of art is incomplete. In recognition of this, artists seem to need to title a work as ‘Untitled’.

Many artistic works rely on words, and the felicitous application of language. Examples include maps, poetry, illuminated manuscripts, art, book design, advertising, film and video, and contemporary websites are modes of communication that rely on words and image. These visual-textual modes of communication are typically so interwoven that often the words seem to be fused as a component graphical image as well as having a linguistic connotation. We can refer to these works as having a cohesive interdependence, with unified graphics and text, as a complex verbal-visual sign. Again, we repeat that word and image, or text and object, are important mediators of meaning when used by the artist to guide the cognitive retrieval of a relevant meaning within the viewer.

How does the viewer retrieve a relevant meaning? The conjunction of word and image engages our human cognitive capacity to map disparate elements and semantic networks of meaning onto each other. The word plus image guides the cognitive operations behind the retrieval of a relevant meaning. They function to create a vector for the viewer for retrieval of an unexpected but relevant meaning.

Central to this retrieval of meaning is the cultural common ground of the art creator and the art viewer. The text becomes an important grace-note guiding us forward in the retrieval of meaning. As such, the conjunction of word and image has the significant potential to capture the meaningful values within a culture. The cognitive operations that retrieve a meaning from the work of art are reminiscent of those characterised in Relevance Theory, within the field of linguistic pragmatics. Relevance theory is a framework for the study of cognition, proposed primarily in order to provide a psychologically realistic account of communication. Pragmatics is the study of how linguistic properties and their associated contextual factors interact in the interpretation of utterances. A sentence of a language can be considered as an abstract object with various morphosyntactic and semantic properties that are organised according to the grammar of the language. Pragmatics examines language in use in communication.

Relevance Theory considers that the actual act of communicating raises in the intended hearer particular expectations of relevance which are enough to guide the hearer towards the speaker’s meaning (Noveck and Sperber[16] 2004). In Relevance Theory, relevance is defined as a property of inputs to cognitive processes. This include external stimuli, which can be perceived and processed, and mental representations, which can be stored, recalled or used as premises in inference. An input, then, is relevant to a hearer when it connects with the hearer’s background knowledge, for example, knowledge in common ground, to yield new cognitive effects. Cognitive effects are adjustments that update the individual’s set of assumptions resulting from the processing of an input in a context of previously held assumptions. To be more relevant and more worth processing, an Input should yield greater cognitive effects and/or involve a smaller processing effort.

In support of these ideas, Relevance Theory develops two general principles about the role of relevance in cognition and in communication (3):

(3) The role of relevance in cognition and in communication

|

Cognitive principle of relevance:

|

Human cognition tends to be geared to the maximization of relevance.

|

|

Communicative principle of relevance:

|

Every act of communication conveys a presumption of its own optimal relevance.

|

According to Relevance Theory, the presumption of optimal relevance conveyed by every utterance is precise enough to ground a specific comprehension heuristic (4):

(4) Relevance Theory Comprehension Heuristic

|

Presumption of optimal relevance

|

(a)The utterance is relevant enough to be worth processing.

(b) It is the most relevant one compatible with communicator’s abilities and preferences.

|

|

Relevance-guided comprehension heuristic

|

(a) Follow a path of least effort in constructing an interpretation of the utterance (resolving ambiguities and referential indeterminacies).

(b) Stop when your expectations of relevance are satisfied.

|

Relevance theorists (convincingly) argue that this approach has good explanatory power because it captures the idea that, in interpreting an utterance, the hearer automatically aims at optimal relevance. In this regard, the hypothesis of graded salience, proposed by Peleg, Giora and Fein[17] (2004: 172–186), assumes that more salient meanings are accessed faster, and that context also affects comprehension on-line. They hold that:

It is widely agreed now that contextual information is a crucial factor determining how we make sense of utterances. The role of context is even more pronounced within a framework that assumes that the code is underspecified allowing for top-down inferential processes to narrow meanings down and adjust them to the specific context.

In interpreting an utterance, the hearer will select knowledge from context to process the utterance so that it gives at least adequate cognitive effects with minimal processing effort. It is our view that the same cognitive processes characterised in Relevance Theory allows us to retrieve appropriate meaning from art. We assume the art to be relevant and therefore more worth processing, and the meaning we retrieve from the visual inputs yield significant cognitive effects and a smaller processing effort.

We move on now to another use of words, poetry, where we can see how the selection of knowledge from context to process the poem gives appropriate cognitive effects with minimal processing effort. Common ground is crucial for the retrieval of meaning from the poem. In the poem (5) ‘The Given Note’ by Seamus Heaney[18] (from the collection 'Opened Ground Poems 1966-1996'), the poet describes the way in which a Blasket fiddler retrieves the tune Port na bPúcaí from ‘out of the night’. I quote a fragment from this poem.

(5)

|

On the most westerly Blasket

In a dry-stone hut

He got this air out of the night.

|

Strange noises were heard

By others who followed, bits of a tune

Coming in on loud weather

…

|

Through the language of the poem in describing how a fiddler crafted a tune that came out of the night, the fiddler becomes a metaphor for the poet himself, and his finding insights into human nature through the medium of language. Language is a powerful thing and a rich, shared common ground is necessary to allow us find meaning in this poem.

We get a different sense of this in the 1996 poem (6) ‘Digging’, also by Seamus Heaney[19] (fromDeath of a Naturalist), in which the poet describes his father digging in the bog on their family farm. He admires his father's skill and relationship to the spade in the act of digging turf, but states that he will dig with his pen instead. This demonstrates Heaney's commitment as a poet as he names his pen as his primary and most powerful tool for the use of language.

(6)

…

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

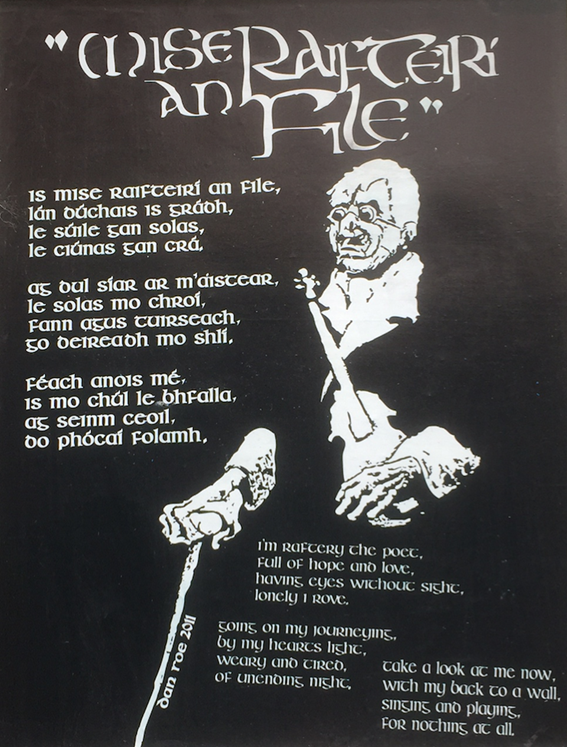

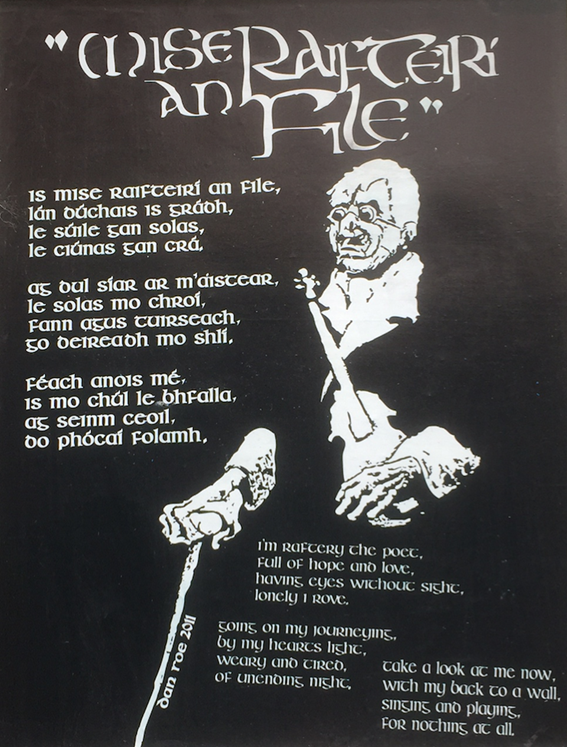

Another example of the expressive power of language comes from Irish by the poet Raftery where the language of the poem ‘Is Mise Raifteirí’ (I'm Raftery) expresses considerable human kindness and warmth (7). Raftery[20] in his poems make rich use of metaphor, for example, the heart is a container of emotion.

(7)

|

Is Mise Raifteirí an file,

Lán dúchais is grádh,

Le súile gan solas,

Le ciúnas gan crá.

Ag dul síar ar m'aistear

Le solas mo chroí

Fann agus tuirseach

Go deireadh mo shlí

Féach anois mé

Is mo chúl le bhfalla

Ag seinm ceoil

Do phócaí folamh

|

I'm Raftery the poet,

Full of hope and love,

With eyes without sight,

My mind without torment.

Going west on my journey

By the light of my heart.

Weary and tired

To the end of my road

Behold me now

With my back to the wall

Playing music

To empty pockets.

|

The street art in Figure 7 is indicative of how the language lives within the linguistic landscape, and how the ideas within the poems resonate with us in a living culture. In particular, this street art illustrates how the cultural constituent of artefact, is the result of the expression of human culture in our world, within the linguistic landscape of Dublin city centre in this instance, where language is found in public spaces in the environment, and word, phrases and images are displayed, discovered and exposed in interesting and significant ways.

Figure 7. Raftery the poet – Street art from Temple Bar Dublin[21]

Staying within the Irish cultural context, writers like W.B. Yeats, through language and poetry, mined the myths and archetypes of the Irish antiquity to create a cultural narrative. The linguistic landscape of our environment, considered in its broadest sense, is a particularly rich context area to explore the connection between culture and language through language found with artefacts of various kinds. The study of the linguistic landscape contributes to our insights on the relationship between culture, common ground and language[22]. The Irish landscape itself plays a role in this cultural narrative as it is littered with monuments and artefacts that are important with our sense of our culture, our connection to place, and who we are (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Newgrange – in the Boyne Valley, county Meath[23]

One example is the Tara area of the Boyne valley in county of Meath, north of Dublin. Here, we find Newgrange, a 6,000-year-old passage tomb and temple with astrological, spiritual, religious and ceremonial importance. Building Newgrange was a significant cultural achievement for this Neolithic civilization. Additionally, Irish place names are like a rich cultural overlay available to us to explore within our linguistic landscape. Place names are often one of the few surviving indicators of a previous language and culture, and we can find ample vestiges in the place names of Ireland (Bally/Baile ‘town’, Kill/Cill ‘church’, Inis ‘island’, Dun ‘fort’, etc.).

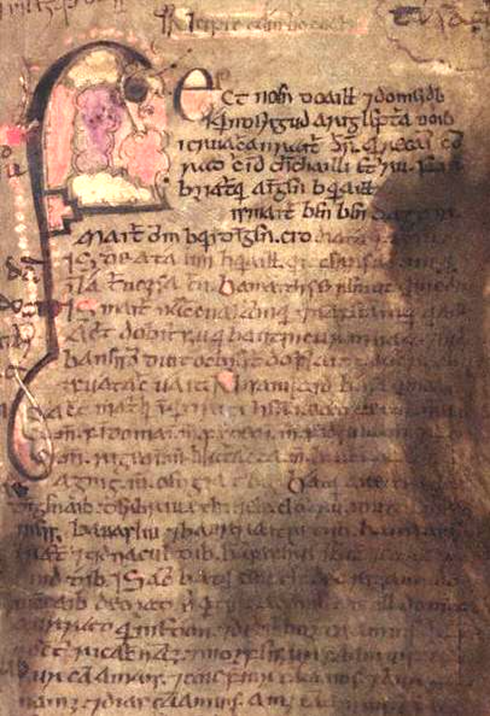

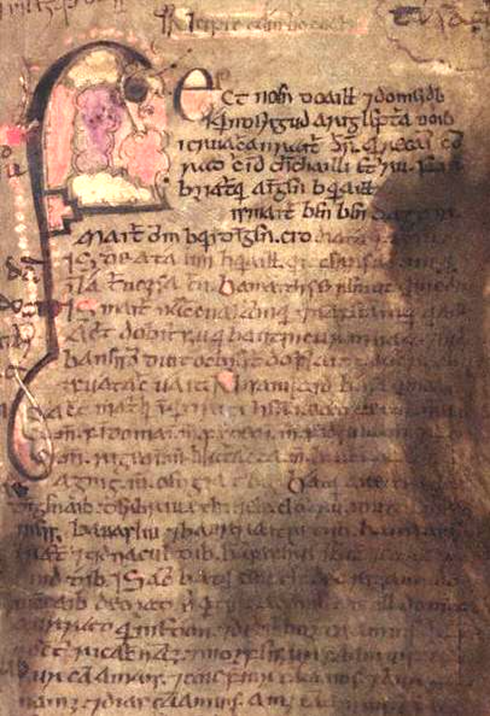

Another example (see Figure 9) of a language-based cultural artefact that contributed to the Irish culture narrative through language is the ancient book Lebor Gabála Érenn (known in English as The Book of Invasions).

Figure 9. Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland)[24]

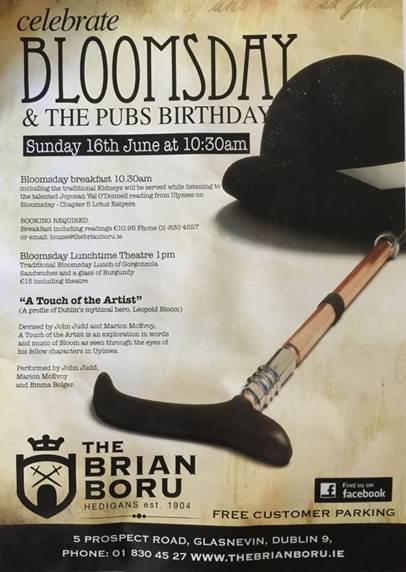

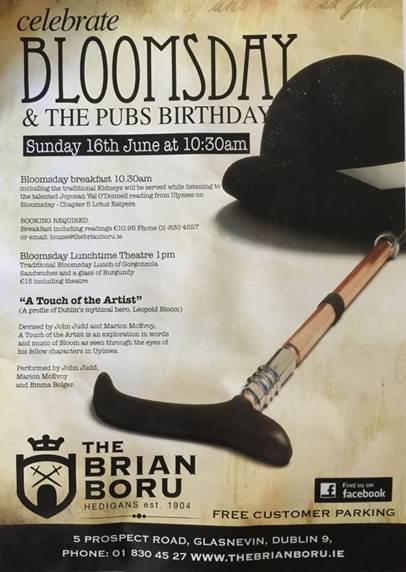

This is a collection of poems and prose narratives that purports to be a history of Ireland and the Irish from the creation of the world to the Middle Ages. This book synthesised narratives that had been developing over earlier centuries of life in Ireland. A more recent example of a book that contributed to the Irish culture narrative through language is Ulysses (1922) by James Joyce[25], a novel about a day in the life of ordinary people in Dublin on 16th June 1904. The book was written by Joyce in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris between 1914 and 1921. It tells in great detail many incidents of the life of Leopold Bloom and those around him on that single day. Ulysses was met with widespread scandal and controversy when Joyce first published the novel as a complete book in Paris in 1922. Since then, however, the 16th of June has since become celebrated in Ireland (and internationally) as Bloomsday (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Poster advertising Bloomsday breakfast, lunch & Bloomsday activities[26]

Every year in Dublin on that date, hundreds of Dubliners dress as characters from the book – Stephen with his walking cane, Leopold wearing a bowler hat, Molly wearing her petticoats – to assert a connection with the text and its events. The celebration allows Dubliners to project a sense of community on the streets of Dublin in a festive carnival-like atmosphere. Dubliners re-enact scenes from the novel in places mentioned in the novel at the appropriate time according to the Bloomsday schema based on the structure of the novel, including, for example, Eccles Street, Sandycove's Martello Tower, and Ormond Quay. Bloomsday, as a conceptual schema, organises actions and experiences, and structures individual perception of events, building frames and basic cognitive structures to guide one’s perception of reality. The Bloomsday schema has participants, temporal dimensions and spatial locations. It is culturally motivated and shares a common understanding amongst its participants – a shared common ground.

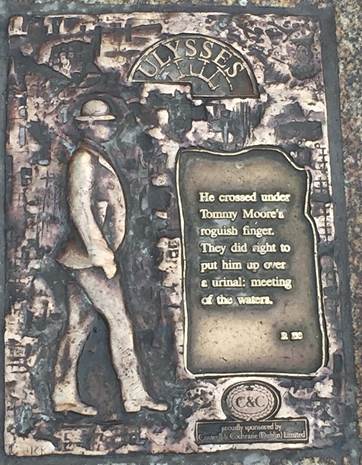

Figure 11 shows elements of Ulysses recorded on the linguistic landscape of Dublin. The context for Bloomsday is activated and constructed in the ongoing interaction and is eventually shared by the Bloomsday participants in the construction of the common ground.

Figure 11. Two of many plaques embedded in Dublin paths celebrating Ulysses[27]

Context has a central role in Bloomsday, as a component of cognition in the determination of the conditions of appropriate knowledge activation as well as the limits of knowledge. Context includes cultural knowledge, general knowledge and shared communal beliefs, and the experience that arises from the resulting interplay of culture and social community.

All around us, language transforms our world and provides us with meaning in context. We have argued that language depends on culture and language organises culture. We have argued for a view whereby culture is the set of values shared by a group and the relationship between these values, along with all the knowledge (language, grammar, stories, sounds, meaning, and signs) shared by a community of people, forming a particular worldview and common ground, and transmitted according to their traditions. We proposed that meaning in culture is facilitated by language and that language, in turn, draws on cultural common ground while the cognitive processes that people employ to retrieve a meaning are precisely those characterised within Relevance Theory.

Additionally, we argued that these cognitive processes also apply to retrieving meaning from art, music, poetry, and artefacts within the linguistic landscape. According to relevance theory, an input is relevant to an individual when, and only when, its processing yields such positive cognitive effects. Typically, the greater the positive cognitive effects achieved by processing an input, the greater its relevance will be. The greater the effort of perception, memory and inference required, the less rewarding the input will be to process, and therefore less deserving of attention. Relevance therefore may be assessed in terms of cognitive effects and processing effort.

Human cognition tends to be geared to finding meaning and the maximisation of relevance but an informed and mutually agreed common ground is necessary before any communication or dialogue can effectively take place. We argued that, in finding meaning, there is a deep connection between language, cognition, communication and culture. Language, common ground and our cognitive processes allow us to retrieve a relevant meaning with least cognitive cost characterise the connection with culture. it’s complicated of course, and very interesting while also very human, and very worthy of our attention.

[1] Kecskes, Istvan and Fenghui Zhang. 2009. Activating, seeking, and creating common ground: A socio-cognitive approach. Pragmatics & Cognition 17:2. 2009, 331–355. Doi 10.1075 / p&c.17.2.06kec issn 0929–0907 / e-issn 1569–9943. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

[2] Eagleton, Terry. 2016. Culture. Connecticut: Yale University Press.

[3] Eliot. T.S. 1973. Notes Towards the Definition of Culture. London: Faber & Faber

[4] Declarative knowledge describes known concepts, facts and entities, including simple statements that are asserted to be either true or false. It includes a matrix of attributes and their values so that an entity or concept may be fully described. Procedural knowledge of processes, rules, strategies, agendas, and procedures describes how something operates, and provides directions on how to do something. Heuristic or experiential knowledge guides our reasoning process. It is empirical and represents the knowledge compiled through the experience of solving past problems. Meta knowledge is high-level knowledge about the other types of knowledge. We use this type of knowledge to guide our selection of other types of knowledge for solving a particular issue and to enhance the efficiency of our reasoning by directing the reasoning processes. Structural knowledge is to do with our sets of rules, concept relationships and concept to entities relationships. Our mental model of concepts, sub-concepts, and entities with all their attributes, values, and relationships is typical of this type of knowledge.

[5] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/language [last accessed 10/9/2018]

[6] Sharifian, Farzad. 2011. Cultural Conceptualisations and Language: Theoretical framework and applications (Cognitive Linguistic Studies in Cultural Contexts). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Sharifian, Farzad. (ed.). 2015. The Routledge Handbook of Language and Culture. New York/London: Routledge/Taylor and Francis.

[7] Nolan, Brian. 2012. The structure of Modern Irish: A functional account. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing Company.

[8] Image from https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/319192692324857963/ [last accessed 10/9/2018]

[9] Image from https://i.pinimg.com/originals/84/c4/a4/84c4a495d52a58640ab33613798d2a7c.jpg [last accessed 10/9/2018]

[10] Dixon Hunt, John., David Lomas and Michael Corris (eds). 2010. Art, word and image: 2000 years of visual/textual interaction. London: Raektion Books.

[11] Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Kells#/media/File:KellsFol292rIncipJohn.jpg [last accessed 10/9/2018]

[12] Diedrichsen, Elke. To appear. On the Interaction of Core and Emergent Common Ground in Internet Memes. Internet Pragmatics, special issue on the Pragmatics of Internet Memes. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

[13] Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masterpiece_(Roy_Lichtenstein) [last accessed 10/9/2018]

[14] Image from http://www.robertballagh.com/paintings.php [last accessed 10/9/2018]

[15] Image from http://www.robertballagh.com/paintings.php [last accessed 10/9/2018]. Based on the painting of Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix commemorating theJuly 1830 Revolution which deposed KingCharles X of France. A woman personifyingthe concept of Liberty leads the people forward over a barricade holding the flag of theFrench Revolution– thetricolour, which remains France's national flag. The figure of Liberty is a symbol of the French Republic.

[16] Noveck, Ira A. and Dan Sperber. 2004. Experimental Pragmatics. Hampshire UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

[17] Peleg, Orna., Rachel Giora and Ofer Fein. 2004. Contextual strength: The Whens and Hows of Context Effects. In Ira. A Noveck and Dan Sperber. Experimental Pragmatics. Hampshire UK: Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. 172–186.

[18] Heaney,Seamus. 2002. Opened Ground: Poems 1966-1996. London: Faber & Faber.

[19] Heaney,Seamus. 2006. Death of a Naturalist. London: Faber & Faber.

[20] Raftery was a poet, and a wandering musician with a fiddle. Like many vagrant 18th century musicians, he was blind (see Figure 7). This poem is famous and was written in a time of great poverty and hardship in Ireland, just before the famines of the 19th century. Raftery became a travelling bard known as the ‘Kiltimagh Fiddler’ and passed most of his time in area around Mayo and. Galway. He died on Christmas Eve 1835. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine_Ó_Raifteiri [last accessed 10/9/2018]

[21] Photo of the street art by this author. Note that the English translation in the street art is slightly different that the (more accurate) text in example (7).

[22] Mallory, J. P. 2013. The Origins of the Irish. London: Thames and Hudson.

[23] Image from https://www.opw.ie/ga/annuachtisdeanai/2013/articleheading,25062,ga.html [last accessed 10/9/2018]

[24] Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lebor_Gabála_Érenn [last accessed 10/9/2018]

Lebor Gabála Érenn(The Book of the Taking of Ireland) is a collection of poems and prose narratives t purporting to be a history of the Irish and Ireland from the creation of the world to theMiddle Ages It was written by an anonymous writer in the 11th century and it synthesised narratives developing over the many centuries.

[25] Joyce, James. 2008. Ulysses: The 1922 text (Oxford World's Classics).Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[26] Photo by this author

[27] Photo by this author

![]()