The 5-Symbols Art Task Series is

tailored for pedagogical practice, and

its aim is to facilitate students’ self-expression. It contains five

given symbols: these are a ship, house, heart, tree, and an optional

symbol. All of these reflect different parts of the personality.

The five symbols are embedded in a story of an

imaginary journey. In this journey we are sailing, so first we have to

design our own boat. The boat is the first symbol. The boat or ship

represents getting away from the ordinary days, and a journey into

ourselves.

In European culture in

many cases ships are symbols, and

they can have special attributes. For example, in a number of

mythological and religious stories, such us Noah’s ark in the Old

Testament, or the tale from ancient Greece about the journey of

Odysseus. Also Kharon’s boat is not just a means of transportation, but

it symbolizes transmission between the world of the living and the

dead. We can also see special boats in today’s popular blockbusters,

like the Black Pearl in

The Pirates

of the Caribbean.

The equipment, the size or the secure or unsecure

visualization of the ship shows the background of a person and his or

her senses of security in real life. We can see this if we compare the

two boats in Figures 1 and 2. The first is a large and well-equipped,

safe ship, but the other one is sinking right now. There is a man

standing in a tiny little life boat, and a big shark is about to eat

him. He is screaming. These boats clearly show the differences between

the two students’ sense of security.

While we are sailing, we get into a heavy storm and

we get shipwrecked. We are marooned on an island, where we find a

house. The house is the second symbol. The House-Tree-Man Test (H-T-P)

by Buck is a well-known psychological drawing test.

3 Based on

Buck’s test I expect that the house is a symbol of family

relationships. However, because of the storyline, the house in my

method symbolizes the drawer’s conception of a shelter in a difficult

situation. Figures 3–5 show some examples of the different

house-drawings, and the differences of sense of security, when the

drawing person is in trouble. The drawer of Figure 3 said:

This is a

ruinous house. Nobody lives here. I don’t feel like going inside.

Figure 4 is a castle with flowers in the garden.

Figure 5 was made by a 14 year-old Romani boy. His

house is a prison, and based on his comment I assume that this theme

reflects his conception about difficult situations or about his future.

He said:

This is a prison at the end

of the world. Nobody could get out

of here! There is a man standing in the left corner. He is crying and

holding up his arms, asking for help.

After we have taken a rest in the house, we start

discovering the island. In the middle of the island there is a cave,

and deep in the cave we find two magic mirrors. The first mirror shows

our heart instead of our body. Our own heart is the third symbol.

Generally heart is the symbol of love, or other feelings and desires.

In addition, the heart is a state of mind and a feature of the human

character. I gathered some common idioms related to heart, e.g. heart

of stone, lose your heart to a man, heart of gold, one’s heart goes

out, my heart bleeds for you, heart-to-heart, one’s heart sinks, etc.

Figures 6–8 are examples of adolescents’ drawings about their own

heart. These pictures reveal different feelings and moods.

In the second magic mirror we can see ourselves

altering into something else. This is an optional symbol about our

selves. Optional symbols are often animal figures, plants, brand names

or logos, and beloved objects. They reveal the conscious or desired

aspect of a personality. After that we climb out of the cave. There is

a tree near the exit of the cave. The tree is the last symbol. Drawing

a tree is a psychological drawing test similar to Buck’s house

test.

4 It reveals deeper

feelings of the drawer, and the tree

symbolises the whole personality. Further on I show examples for the

tree and optional symbol drawings.

At the end of the story we are asleep under the

tree, and the rescue team with our friends find us there. This is the

end of our imaginary journey.

Projective Drawings in Education

Drawings can be regarded as a representation of the psychic state.

Projective drawing tests are common in psychological practice, for

example Goodenough’s Draw-A-Man test

5,

the Rorschach test,

6 Buck’s

House-Tree-Man test, Koppitz’s intelligence test,

7 and so on.

Drawing is a projective cue, and the person can express herself through

it. In psychological practice, projective drawing tests are used to

reveal the unconscious parts of the personality, to diagnose mental or

personality disorders or to help therapeutic procedure.

At the same time, in the educational context

projective drawings have another function, which requires another point

of view. It is very important to see clearly how we can use the

projective method in education. In the school, drawing is not part of a

therapeutic procedure, and it is not a diagnostic tool. Instead,

projective drawing is a tool of nonverbal communication, and helps

self-expression through visual representation.

According to Kristóf

Nyíri, “everyday thinking and communication, as well as scientific

theories, involve more than just verbal language. They involve images,

too.” Pictures are “

natural carriers

of meaning”.

8 Pictures

are

able to convey the kind of notions which the verbal mode is not, so

drawing can be a tool for understanding teenagers. Furthermore,

teachers have to use the projective method prudently, because the

therapeutic and educational procedures do not have the same roles.

Also, teachers have to be aware of their limit of competence, and they

should cooperate with other experts in the school if it is necessary

(for example the school psychologist, a family advisor, a child

protection expert, or a special education teacher). Carefulness with

the explanation of symbols is also required from them. In all cases the

meaning of the symbolic drawing is based on the drawer’s own

interpretation. I discuss the possible explanation of drawings in

detail in some other publications of mine.

9

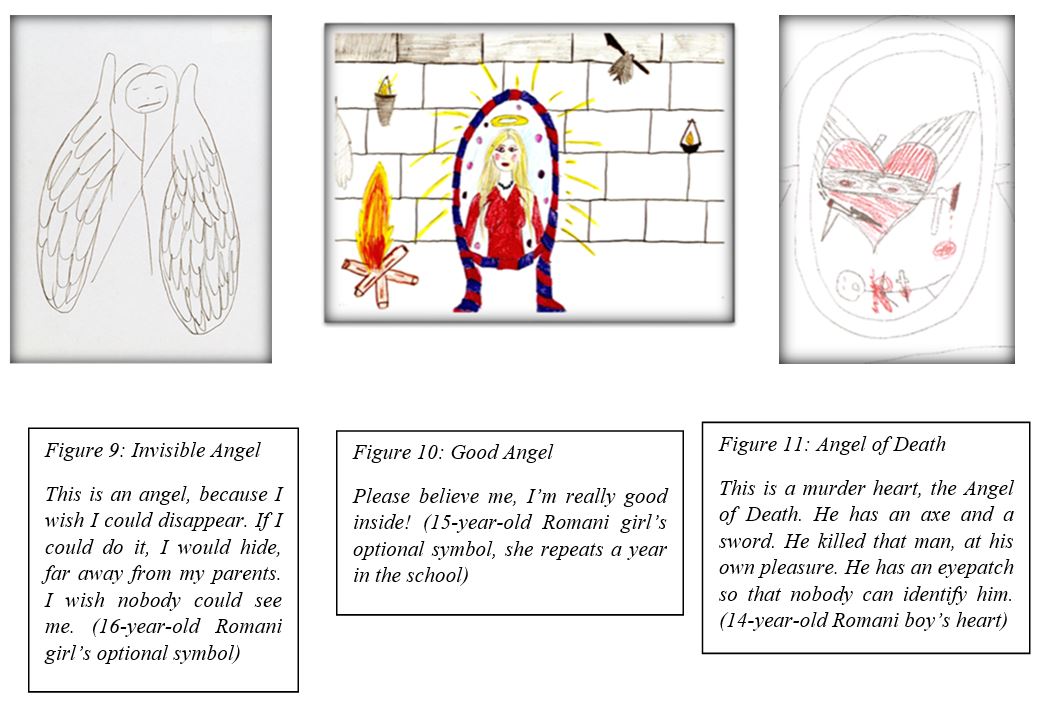

The following examples show that the same motif can

denote absolutely different contents. Figures 9–11 all represent

angels. Below the pictures we can read the drawing teenagers’ own

interpretations, and these make it clear that their feelings and

thoughts were different in each case. It is possible to understand the

meaning of angel as a symbol if the drawer is taken as a starting

point, independently of the teachers’ own convictions or their

emotional state.

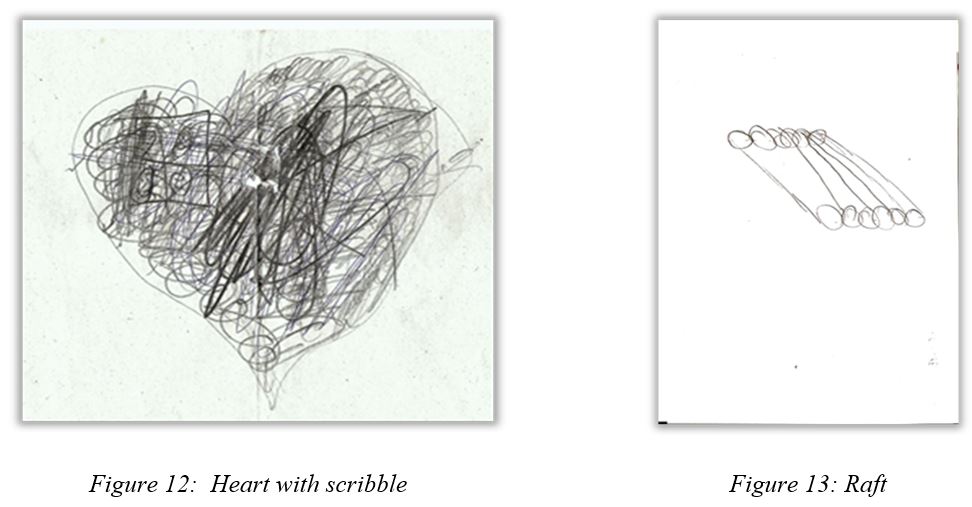

On the other hand, projective drawing is neither a

tool of teaching visual arts, nor a measuring instrument. In the school

the aim is not to develop drawing skills but to help self-expression

through shaping their own symbolic pictures. These drawings sometimes

have very low level of representation, because in this case spatiality

and realistic depiction are not important. So using projective drawings

in education requires a new assessment procedure, where the

expressivity and substance of the drawings becomes conspicuous. Figures

12 and 13 are examples of low levels of representation, but strong

self-expression. Figure 12 is a heart full of scribble. It shows

painful and angry feelings with very simple device. Figure 13 is a

raft. This is the drawer’s own boat. He is unable to navigate it,

without having a sail or power engine. It shows the insecure feelings

of the drawer.

5-Symbols Art Task series is a projective type of method, but

does not serve therapeutic purpose. This task aims at drawing symbols,

and these pictures show the veracity of the inner world instead of the

depiction of the outside world. Symbols support self-understanding,

because symbols always have two meanings.

10 The

everyday meaning gives you the feeling of security, and the hidden

meaning of the symbols make self-expression possible. So symbols allow

people to reveal themselves and stay safe at the same time. They have

the option to choose between these meanings. To draw symbols is an

opportunity for the students for self-expression and they can choose to

take it or not.

I based my views on the sociological concept of the

interpretation of symbols. It sees symbols as a reflection and a

concentrated expression of the inner self. Visual symbols are a

connection between the inner world and the community, because these

pictures reveal the drawer’s thoughts and emotions.

Veracity of Adolescents’ Drawings

Usually feelings and emotions are the most important elements in the

drawings of the symbols here discussed. As I mentioned earlier, the

drawer’s own annotation is the main aspect for the explanation of the

drawing. Whatever they say about their drawing, they say all of it

about themselves, because these symbols reflect the personality.

Sometimes these feelings are connected to forbidden or ashamed

contents, for example aggression, anxiety, or inferiority complex.

Andrea Kárpáti and Tünde Simon review symbolization processes in a

variety of classic and new media. As they write: “Symbols are elicited

by tasks that are emotionally engaging and thus may result in the

formulation of a personal message. Verbal utterances of aggression,

anxiety and phobia are normally suppressed in a school environment, but

may be freely expressed during an art class.”

11

Some examples demonstrate aggressive or ashamed

contents in the drawings. Figures 14 and 15 show aggressive or painful

feelings.

Figure 16 at first sight is a common drawing of a

heart. There are no decorative elements, no figures, just some colours.

But the drawer tells us that they represent her suffering pangs of

jealousy. Figure 17 is a 13-year-old girl’s optional symbol. She

portrays a tattered and humbled young girl, who is her symbol. Very

likely it would be difficult to utter these feelings, but through

drawing symbols it is feasible.

Usually these drawings densify a lot of complex or

ambivalent thoughts. It is very difficult to denote them in a verbal

way, but the picture is a good tool for it. Figure 18 shows a hamster

and a snake. It symbolizes the relationship between people. Figure 19

is a variation of a well-known sign, a smiley face. It shows ambivalent

thoughts about the drawer’s own personality.

During my researches I compare the results of

the 5-Symbols Art Task Series to a verbal test about personality. This

test is a Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SDQ by Robert

Goodman.

12 In some cases the

drawing shows such deep feelings like

mourning, whereas the verbal test shows a totally trouble-free status.

It seems they could not talk about their problems, but they could draw

about it. Examples for this are shown in Figures 20–22.

Figure 20–22 are all from the same boy. This boy was

mourning deeply when he made these pictures. His father died suddenly a

few months before, and the boy had not spoken a word about it with

anyone. His teachers and his mum worried about his being emotionless.

But these drawings with his own symbols show his inner world clearly.

The little size and the lines show anxiety, and his words about the

pictures talk about painful feelings, mourning and loneliness. As in

the mourning boy’s case, sometimes symbol drawing can be a better tool

for self-expression than words.

In Figures 23 and 24 we can see two

pictures of a 14-year old boy. The drawings were made during his

parents’ divorce. These pictures show his feelings about it. His

symbols are full of fighting, intimidation and defence.

Summary and Conclusion

The visualizations made by pubescent children can contain important

information about the individual. Based on my research I claim that we

can use projective drawings like 5-Symbols Art Task Series successfully

in education. They are a useful pedagogical tool not just in Art

education, but they help class community work too. They promote

self-knowledge and self-communication, conduce to integration of the

outermost students, reveal the problems of students who are difficult

to handle, lead to understanding conflicts, or contact with parents. It

seems that in some cases drawing is a better option than the verbal

mode. Projective drawings not only help to come to truly know

adolescents, but they contribute to – as mentioned above – possible

cooperation with other experts in the school, for example the school

psychologist, a family advisor, a child protection expert, or a teacher

for pupils with learning difficulties.

A 13-year-old boy said about his own heart:

This is

an inner light, which is looking for a way out (Figure 25).

Drawing can

be an appropriate tool for letting the inner light out!