Visual argumentation in the Hungarian Competition Authority's

proceedings1

Introduction

Advertisements are a shared subject

of inquiry for media theory and

argumentation the-ory. Commercial interests provide a prime field for

observing innovative persuasion techniques. Marketers utilize verbal

tools and visuality; these tools are usually analyzed in rhetorical

terms and with good reason, for the persuasive power of advertisements

is mainly rhetorical. Moreover, one might even go on to say that this

is the only the kind of analysis available, since we cannot express

arguments by visual means. However, informal logicians have claimed

that visual arguments are not only possible but actually exist and can

be analyzed and evaluated in roughly the same way as verbal arguments.

In this paper we will argue that they are right. In particular, we will

explore in some detail how visual arguments can be reconstructed and

point out the similarities to and the differences from the

reconstruction of verbal arguments. We will then substantiate these

claims by providing a complete reconstruction of the visual (strictly

speaking, multi¬modal) argument given by Unilever for the superiority

of its product, Dove Intensive Cream, in a famous and

controversial

2

commercial

involving the “tulip test”.

We will start with a brief description of the informal logic tradition

and explain how it makes room for visual arguments. Then, relying on

this understanding of visual arguments, we are going to explain what

steps the reconstruction of visual arguments involves. Finally, we will

use the Dove commercial to demonstrate how these steps look like in

practice.

The Informal Logic Tradition

In the late 1970s a group of

philosophers started to develop

“non-formal standards, procedures of analysis, interpretations,

evaluation, critique and construction of argumentation in everyday

language”.

3 Their

main motivation was that formal logic is

rather hard to apply to everyday arguments. Everyday arguments – like

the student’s argument for deserving a better grade, the husband’s

argument for getting a new car – are never ex-plicitly formulated as

deductive arguments and trying to put them in deductive form requires

the addition of further premises. These additional premises, however,

often seem arbitrary in the sense that there is little justification

for supposing that the arguer would accept them. Indeed, these

additional premises would often be obviously false. So in-formal

logicians jettisoned the idea of deductive validity together with the

argument forms which may be assessed in terms of deductive validity.

The new understanding of argument structure and validity they developed

has made it possible to raise the question whether visual messages can

constitute arguments. The majority of theoreticians has answered this

question affirmatively.

4

The Idea of Visual Argument

From the perspective of formal logic

the idea of visual argument looks

odd to say the least: premises and conclusions ar sentences, but

pictures are not made up of sentences. But O’Keefe has suggested a

broader conception of argument which is more hospitable to visual

arguments. On his understanding arguments involve “a linguistically

explicable claim and one or more linguistically explicable

reasons”.

5 This

implies that arguments do not necessarily have to

be linguistic, they only have to be

linguistically

explicable. Visual

contents are certainly linguistically explicable, since we can describe

in words what pic-tures show. To put it differently, what matters for

arguments is propositional content, and propositions can also be

expressed by visual means. This conception of argument makes

theoretical room for visual arguments. Informal logicians then went on

to argue that some pictures described in the way we usually describe

pictures actually constitute arguments. Even though these arguments are

rarely complete in the sense of explicitly containing the claim and all

the reasons, verbal arguments are also often incomplete, for the simple

reason that what the recipient of the message knows or can easily

figure out does not have to be explicitly stated.

6

The Reconstruction of Visual Arguments

So the only important difference between visual and verbal arguments is

that the claim and reasons making up a verbal argument are linguistic,

whereas those making up visual arguments are at least partly merely

linguistically explicable. Verbal arguments thus consist of a

linguistically formulated claim, i.e. conclusion and one or more

linguistically formulated reasons, i.e. a single set or multiple sets

of premises, whereas in visual argu-ments at least some of the premises

or the conclusion is not expressed in linguistic form. In the case of a

simple argument relying on a single reason the picture is this (Table

1).

| Verbal

argument |

Argument |

Visual

argument |

| linguistic |

Premises

Conclusion

|

linguistically explicable |

Table 1

The question we have to address now

is how this difference shows up in

the reconstruction of visual arguments. What informal logicians mean by

reconstruction is a fully explicit and transparent statement of the

argument, which contains all elements necessary for its evaluation. So

reconstruction involves more than a lay understanding of the argument –

it is not a skill which everyone possesses but a learned art drawing on

technical concepts. The reconstruction of an argument consists of the

following elements:

- Identifying the conclusion.

- Identifying the premises.

- Rephrasing the sentences.

- Making implicit elements explicit.

- Building up the structure of the argument.

These should not be conceived as consecutive steps of reconstruction,

because reconstruction, which is a sophisticated process of

understanding, like all other processes of understanding, moves in a

hermeneutic circle. It is by identifying the conclusion that we may

select the parts of the text which function as premises and set them

apart from other parts, like explanations, incidental remarks, purely

rhetorical elements, etc. But it is only by identifying the premises

that we can understand exactly what conclusion the author of the text

is arguing for. These two elements are present even in the lay

under-standing of arguments. However, a reconstruction involves more.

First of all, the possible ambiguities of the text need to be resolved.

The terminology must be unified (e.g. in the student’s argument for a

better grade which involves both the terms “unfair” and “unjust” we may

have to substitute one for the other depending on how the argument

goes). It is changes like these which the term ‘rephrasing the

sentences’ signifies. In addition, the implicit elements must be made

explicit otherwise the relevance or failure of relevance of the premise

cannot be assessed. (E.g. the student’s showing his detailed notes of

the readings is relevant only because this demonstrates that he has

studied a lot – to which the teacher may respond that it is not the

amount of studying which is relevant for the grade but whether the

material has been learned.) When all the premises and the conclusion

have been layed out, it needs to be spelled out how they are connected,

how the premises are supposed to support the conclusion. (E.g. if the

student explains that he has studied a lot and he has only one point

missing for the passing grade, is he advancing two separate reasons for

his claim of deserving a better grade, or is he arguing that it is in

light of his hard work that the missing point should be ignored?)

When it comes to visual arguments, we cannot simply

identify the conclusion and the premises, since we do not have a

linguistic text in which we can isolate them. What we need instead is

their linguistic formulation. Continuing down the list, pictures and

films, being non-linguistic, are free of the occasional linguistic

ambiguities and inaccuracies, and this renders rephrasing sentences

superfluous; if there are not any sentences, there is nothing to

rephrase. The rest of the elements remain the same. Visual arguments

may contain implicit premises just as verbal arguments do. It is worth

drawing attention to the distinction between linguistic formulation and

addition of implicit elements. Linguistic formulation transforms the

visual argument into a verbal one, whereas making the implicit explicit

consists in providing what is missing. Linguistic formulation consists

in changing the modality of content, making the implicit explicit

amounts to enriching the content (Table 2).

|

Verbal

argument

|

|

Visual

argument |

1.

|

Identifying the conclusion.

|

1.

|

Linguistic formulation of conclusion. |

2.

|

Identifying the premises. |

2.

|

Linguistic formulation of premises. |

3.

|

Rephrasing the sentences. |

3.

|

---- |

4.

|

Making implicit elements

explicit. |

4.

|

Making implicit

elements explicit. |

5.

|

Building up the structure.

|

5.

|

Building up the structure.

|

Table 2

It seems, then, that the

reconstruction of visual argumentation follows

broadly the same method as the reconstruction of verbal arguments. It

is worth pointing out that there are arguments termed “multimodal”,

7 which feature both

verbal and visual elements. Indeed, commercials

making use of visual argumentation are typically multimodal, and the

Dove commercial to be analyzed is no exception.

Given this picture of the reconstruction of visual

arguments it is clear that the evaluation of visual arguments (e.g.

identifying unacceptable premises or fallacies) is also fairly similar

to that of verbal arguments. The reason is that reconstruction amounts

to a verbal representation of the argument, and the verbal

representation of an argument is a verbal argument, and as such, all

the usual methods of assessment of verbal arguments are appropriate.

Argument Schemes

Before offering a reconstruction of the Dove commercial we need to say

a few words about the apparatus to be deployed. Informal logicians have

suggested various conceptual devices to replace the apparatus of the

logical connectives geared to capturing deductive structure. The one we

will make use of, the apparatus of argumentation schemes, bears some

similarity to the logical forms of deductive logicians. A valid logical

form is an abstract structure made up of linguistic elements

characterized solely in terms of their identity or non-identity and

logical connectives such that if it is filled in with linguistic

elements in a way which renders the premises true, then the conclusion

is also necessarily rendered true. An argumentation scheme is also an

abstract structure which can be filled in with various linguistic

elements. But filling it in with linguistic elements which make the

premises true does not necessarily make the conclusion true. It makes

the conclusion only presumptively true, meaning that we may accept the

conclusion as true as long as we are not given a stronger reason

against the conclusion or a consideration that undermines the argument.

Argument schemes filled in with true premises thus supply only

defeasible justification for the conclusion. These argumentation

schemes are also constituted in parts by identical linguistic elements,

but instead of logical connectives they involve non-logical expressions

such as similarity, cause, sign. Here is a somewhat simplified example:

A is true in this situation.

A is a sign of B.

B is true in this situation.

Filling in “There is smoke over

there” for

A and “There is

fire over

there” for

B, we get a

cogent, even if not conclusive argument for

B.

The argument would be defeated if it turned out the smoke was generated

by a high-powered smoke machine. This basic idea has been spelt out

differently by different authors. Here we will be drawing on Walton,

Reed, and Macagno’s argumentation schemes.

8

The Case Study

In 2006 Unilever started to air a commercial for a New Dove Intensive

Cream.

9 The

commercial, intended to convince customers that the

Dove product is a better moisturizer than Nivea’s market leading

product, runs as follows.

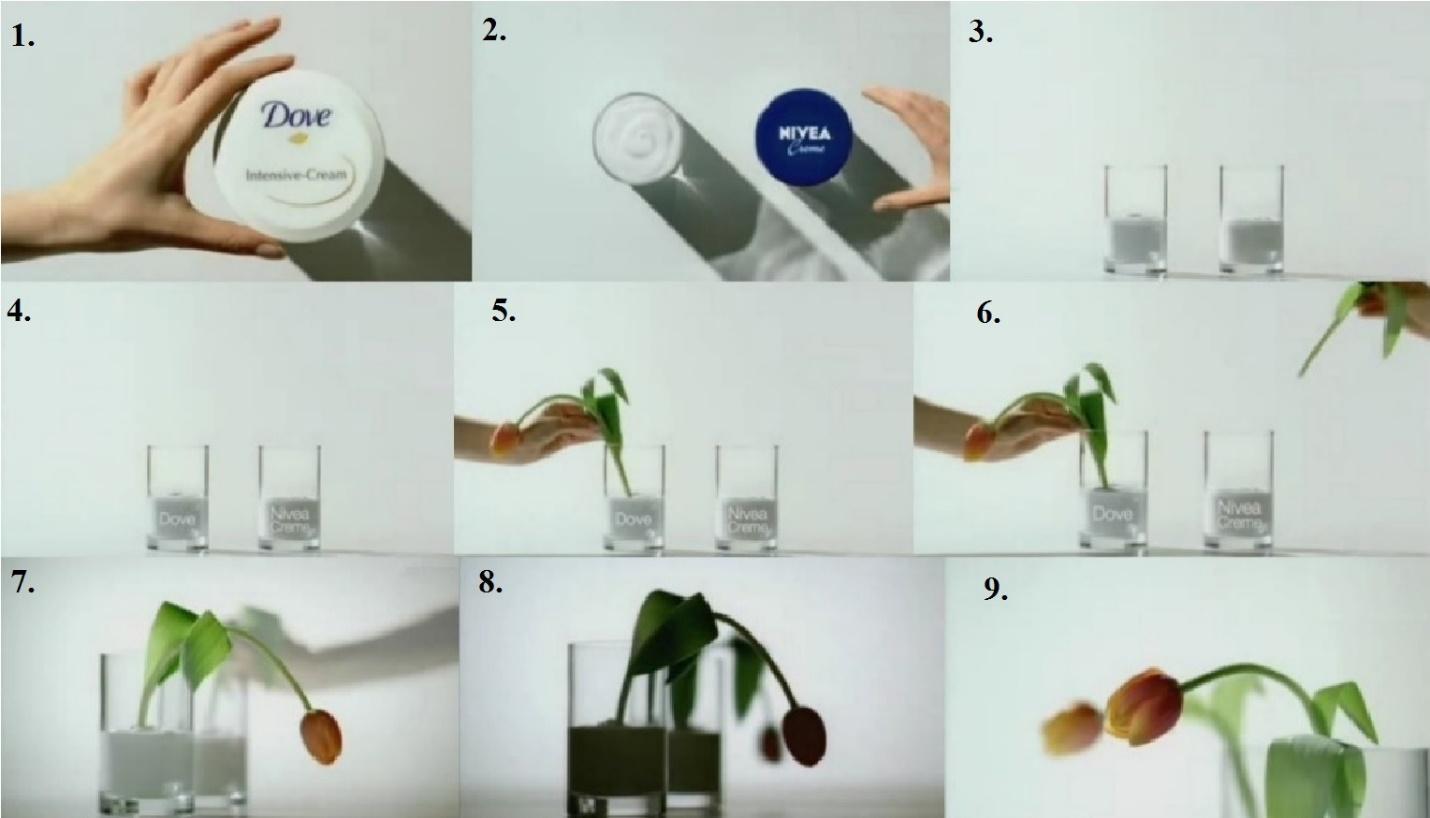

A female hand touches first the Dove then the Nivea product, placed

left and right, respectively (Figure 1/1). Then we are presented with

two containers with the names of the two brands, in which the amount of

cream appears to be the same. After that, the camera focuses on the

containers (Figure 1/2–3–4). A dying tulip is placed first in the Dove

cream (Figure 1/5), then in the Nivea product (Figure 1/6). The flowers

are in bad shape, drooping in opposite directions; they obviously need

water. The camera shows them from the side, which makes their miserable

condition perfectly clear (Figure 1/7). At the 12th second of the

commercial the tulips are left alone to give them time to absorb the

creams (Figure 1/8). The changing light and the ticking of a clock

suggests that time passes. The camera focuses on the tulip of the Nivea

and we see that its condition does not visibly improve (Figure 1/9).

Figure 1

The camera zooms out and we see both tulips now. The passing of time is

shown on a virtual stopwatch (Figure 2/10). After ten hours, the tulip

left in the Dove product looks perfectly healthy, while Nivea’s tulip

is still somewhat drooping - a humiliating defeat (Figure 2/11). The

examiner chooses for the tulip treated with Dove (Figure 2/12). The

abandoned tulip is left in the Nivea moisturizer (Figure 2/13). The

tulip is retrieved from the left container and placed on the right

beside the moisturizer. The text reads “New Dove Intensive Cream” and

“Better moisturization, beautiful skin” (Figure 2/14–15). Notably, in

the Hungarian version of the advertisement the slogan was “Better

mois-turization and beautiful skin” (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The Reconstruction of Visual

Arguments in the “Tulip Test”

Following the procedure outlined earlier, in reconstructing a visual

argument we must start with the linguistic formulation of the

conclusion and the premises. The former presents no difficulties:

since this is a commercial for Dove, the conclusion should be something

like “You should use Dove”. What about the premises? One clue is

supplied by the text appearing at the end of the commercial, “Better

moisturization, beautiful skin”. Having superior moisturizing effect

and thus making the skin more beautiful is certainly a good reason for

choosing Dove.

Notice, however, that it is at the very end of the commercial that this

text appears, which suggests that it might be a conclusion deriving

from what we saw before. So what did we see? We saw that Dove improves

the condition of the drooping tulip much better than Nivea does. As we

all know, flowers need water, so it is by supplying water, i.e. by

moisturizing that Dove improves the condition of the tulip. So one

premise leading to the conclusion presented in text (which, in turn, is

a premise for the final conclusion that we should use Dove) is

something like this: “Dove moisturizes the tulip better than Nivea

does”.

The next question is how we move from this premise to the conclusion

than Dove moisturizes the skin better. It is at this point that the

idea of argumentation schemes can be invoked, as structures linking

premises to conclusions. Since the commercial derives a conclusion

about the skin from a premise about the tulip, it presumably relies on

the idea that the two are similar. This suggests that it is an argument

from analogy. This argumentation scheme is characterized by Walton,

Reed, and Macagno as follows:

Argument from analogy:

- Generally, case C1 is

similar to case C2.

- In case C1, A is true.

- A is true in case C2.10

In the present case C1 is the case of

the tulip, C2 is the case of the

skin, thus the analogical argument offered in the commercial is this:

Argument from analogy in this case:

- The skin is similar to the tulip.

- Dove moisturizes the tulip

much better than Nivea does.

- Dove moisturizes the skin better than Nivea does.

Notice that in identifying the two

premises we perform different

reconstructive operations. In the case of the second premise we merely

put what we saw in the commercial in verbal form, which we called

linguistic formulation. But the pictures do not show anything like the

first premise. We find out about it by asking how the first premise

might lead to the conclusion, and its specific form is identified with

the help of an argumentation scheme. So what we do here is performing

the reconstructive operation of making the implicit explicit.

We have already noted that the final conclusion of the commercial is

that we should use Dove and that it is inferred from the premise that

Dove moisturizes better and makes the skin more beautiful. But how

exactly does the inference go? Moisturizers are supposed to make our

skin more beautiful, which we think is a good thing. This suggests that

the inference utilizes the argument scheme from positive consequences.

This scheme is described by Walton, Reed, and Macagno in this way:

Argument from Positive Consequences:

- If A is brought about,

then good consequences will plausibly occur.

- Therefore, A should be brought about.11

Variable A is in this case using

Dove, and the good conseqences in

question consist in having better moisturized and hence more beautiful

skin. So the argument runs as fol¬lows:

Argument from Positive Consequences in this case:

- If you use Dove, then

it is plausible that your skin will be better

moisturized and be more beautiful.

- Therefore, you should use Dove.

What remains is the final

reconstructive operation, building up the

structure of the argument. The argument from positive consequences

takes us to the final conclusion of the commercial, and the role of the

argument from analogy is to support the premise of the argument.

However, the conclusion of the argument from analogy is not exactly the

same as the premise of the argument from positive consequences, since

the latter mentions beautiful skin (italicized above), which the

former does not. This gap is filled by the textual element of the

commercial, “Better moisturization, beautiful skin”, which can be

construed in this context as saying that better moisturized skin is

more beautiful. Construing it in this way involves the reconstructive

operation characteristic only of verbal arguments, rephrasing the

sentences.

So the argument can be put together

as follows (Table 3):

1.

|

The skin is similar to the

tulip.

|

implicit premise |

2.

|

Dove moisturizes the tulip much better

than Nivea

does. |

explicit visual premise |

3.

|

Dove moisturizes the skin better than

Nivea

does. |

from 1. and 2. by argumentation from

analogy |

4.

|

Better moisturized skin is more

beautiful.

|

textual premise rephrased |

5.

|

If you use Dove, then it is plausible

that your

skin will be better moisturized and be more

beautiful.

|

from 3. and 4. |

6.

|

Therefore, you should use Dove.

|

from 5. by argument from positive consequences |

Table 3

Summary

We have argued first that the

reconstruction of visual arguments

follows by and large the same procedure as that of verbal ones. We have

found only two differences. In place of the identification of premises

and conclusions in verbal arguments we have the linguistic formulation

of premises and conclusion. Also, in the case of visual arguments there

is nothing corresponding to the reconstructive operation of rephrasing

the premises. What is especially interesting and might even be

surprising is the similarity that the operation of making the implicit

explicit is also part of the reconstruction of visual arguments.

To see how the reconstruction works in practice we have provided a

detailed re-construction of a commercial, pointing out how the

theoretically motivated reconstructive transformations actually show up

in practice. The reconstruction also allows to draw a more specific

conclusion, namely that the apparatus of argumentation schemes can be

applied to the reconstruction of visual arguments as well.

[1] Supported by the

ÚNKP-16-3 New National

Excellence Program of the Ministry of the Human Capacity. We would like

to thank István Danka, János Tanács, and Réka Markovich

for their invaluable contribution to the research. We would also like

to thank the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA) for the

financial support provided by grant K 109456.

[2] The Hungarian

Competion Authority initiated a proceeding against this

advertisement and found it deceitful.

[3] F. H. van

Eemeren

et al., Handbook of Argumentation Theory, Amsterdam:

John Benjamins, 2014, pp. 373–374. Eemeren is here referring to R. H.

Johnson and J. A. Blair, “The Current State of Informal Logic”,

Informal Logic 9 (1987), pp. 147–51.

[4] Birdsell’s,

Groarke’s and Blair’s papers in the 1996 special issue of

Argumentation and Advocacy are especially important.

[5] Anthony

Blair,

“The Possibility and Actuality of Visual Arguments”,

Argumentation and Advocacy, vol. 33, no. 1 (1996), p. 24.

[6] Opponents of

the

existence of visual arguments often claim that

pictures are unsuitable for the expression of arguments because they

are intrinsically ambiguous (David Fleming, “Can there be Visual

Arguments?”, Argumentation & Advocacy, vol. 33, no. 1 [1996], p.

11). That is a serious concern which cannot be easily dismissed;

nevertheless, we agree with Blair (op. cit., p. 24) that the difference

between the verbal and the visual in this respect is merely a

difference in degree. We trust that the reconstruction of the

commercial below at least illustrates that this concern is unfounded.

[7] J. Anthony Blair,

“Probative Norms for Multimodal Visual Arguments”, Argumentation, vol.

29, no. 2 (2015), pp. 217–233.

[8] D. N. Walton et

al., Argumentation Schemes, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2008.

[9] Unilever Germany

–

tulip test:

http://www.tvspots.tv/video/42773/unilever-germany-tulip-test.

[10] D. N. Walton et

al., op. cit., p. 315.

[11] Ibid., p. 332.