Pedagogical development in TAMK – Finnish approach to paradigm shift in education

Background for development of universities of applied sciences in Finland

Higher education has changed a lot

during the past 25 years in Finland. The universities of applied

sciences (UAS) were established in the 1990s when the former college

system became higher education. At the moment there are 22 universities

of applied sciences and 14 universities. Universities and universities

of applied sciences have their own profile and legislation as well.

About 23 000 bachelor-level students and 2200 master-level students

graduate from the UASs annually. It is quite normal that in

universities all students will complete the master’s degree with about

15 000 students getting their master’s degree and 1821 getting their

doctoral degree annually. In UASs it is not possible to complete

doctoral studies.

The objectives for higher education are based on the educational policy

and the government programme. The joint objectives of higher education

for 2025 were established in 2016 by the new government. The four main

objectives are:

- strong higher education units that renew competence

- faster transition to working life through high-quality education

- impact, competitiveness and wellbeing through research and innovation

- higher education community as a resource.

In Finland education is almost

entirely publicly funded and at the moment about 11% of the total

public expenditure goes to education (OECD average 12 %). The Finnish

education level is relatively high. For example, Finland is one of the

top-performing OECD countries in reading literacy, mathematics and

sciences according to the OECD statistics. 85% of adults (ages 25 – 64)

have completed upper secondary level education (OECD average 75%). 47%

of women and 34% of men have completed tertiary education (OECD average

is 35% of women and 31% of men,) (Education at a Glance 2015, OECD)

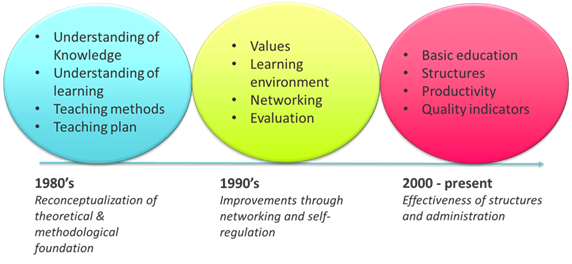

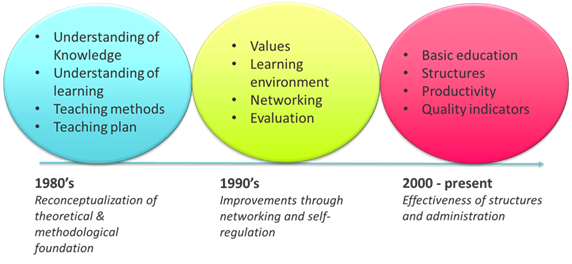

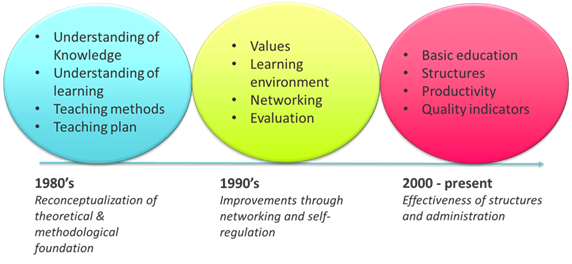

Fig 1: Changes in the Finnish school system since 1980s (According to Sahlberg 2015)

Sahlberg (2015), who has studied the

Finnish school system, emphasizes three different phases in the

development of education in Finland, which can also be recognized in

the development of the university of applied sciences system. The UAS

system was developed in the 1990s. Especially in the 1990s and 2000s

the Ministry of Education supported the development by subsidizing

joint development networks. During that time for example

internationalization, research and development, as well as virtual

courses and virtual pedagogy were developed together with the UAS

sector. The Bologna process has been implemented in Finland since 2002.

It means for example concentration on quality assurance, ECTS

principles, and student-centred learning.

The UAS sector implemented a joint project in 2004. At first the focus

was on supporting the transition to the ECTS credit system. The second

part of the ECTS project concentrated on supporting the universities of

applied sciences in student-centred and competence-based curriculum

design (Arene 2007). The first quality audits were also launched in

2005 and the third round of quality audits are being planned together

with the higher education institutions at the moment. According to

Talvinen (2012) evaluation concerning the first quality audits in

2005-2012 emphasizes that quality assurance has more and more become a

part of everyday practice.

Pedagogical development at Tampere

University of Applied Sciences is based on the strategy, strategic

management and leadership and quality management

Finnish higher education institutions

are relatively autonomous concerning their operations. The education

policy lines out the objectives for the government programme. The

objectives are agreed in the four-year performance agreements made by

the UAS and Ministry of Education and Culture. During the performance

agreement process the main objectives are based on the government’s

education policy and the strategy of the UAS, and the objectives are

integrated together.

During the past twenty years the UAS sector has adopted a more

strategic orientation to management and leadership, which also means

that development of universities of applied sciences is more

systematic. According to Talvinen (2012) quality management is also

more and more inseparable from strategic management and general

development work (Talvinen 2012).

The internal performance planning process as a tool for pedagogical development at TAMK

In Tampere University of Applied

Sciences (TAMK), the objectives for the development work and activities

concerning pedagogical development are established as part of the

internal performance planning process in a dialogue between the

executive board and the schools of TAMK. The strategy and action plan,

where the focus of annual development is set, are checked by the

executive board of TAMK annually. Both the plan and the emergent

strategy are important. They are integrated together during the annual

evaluation.

Fig 2: TAMK’s strategy, performance planning process and quality management

The internal performance agreement

process is a dialogue between the executive board and the schools and

units of TAMK. The process starts with the evaluation done by the

schools and units in TAMK. During the spring term all results and

evaluation data are assessed and based on it the objects which need

development are known. The self-evaluations and reviews create the

basis for the following year’s performance agreement objectives and the

planning phase starts in June.

During the planning phase the schools and units will at first make

their proposition for the following years’ development objectives and

then discuss these objectives with the executive board. At the end of

the discussions and the process the president of TAMK and the director

of the school or unit will sign the agreement.

TAMK’s strategy was formulated in 2010 and revised in 2015. TAMK has a

lot of competences in the field of pedagogy because it has the School

of Vocational Teacher Education, which is one of the five schools of

vocational teacher education in Finland. A notable feature and profile

in the strategy of TAMK is learning and creativity, as well as

wellbeing and health, and business and production. According to the

strategy there are five focus areas. One of these focus areas is

developing professional pedagogy and education. This focus area

encompasses both the teacher education and research, development and

innovations in the field of vocational education. During the past five

years there have been for example projects where TAMK’s School of

Vocational Teacher Education has educated new teachers focusing

especially on digital and mobile education.

One important part of the strategy of TAMK has been digitalization.

According to Haukijärvi (2016) digitalization challenges institutions

to develop on every domain and aspect. It is not enough to change

teaching and learning models but changes are needed in the whole

organisation. Haukijärvi (2016) also did a longitudinal research

concerning the process on how to apply and develop digital strategy in

TAMK. He stated “ there is no strategy for digitalization, but a

strategy for ensuring sustained competitive advantage in the digitally

connected world”. (Haukijärvi 2016) Such a comprehensive approach

supports the higher education institution in developing education and

supporting teachers, students and researchers in their work.

Teacher’s continuing training at TAMK

Higher education undergoes a

transition which is the reason for why teachers also need continuing

training and lifelong learning. Such intellectual capital is the most

important for higher education. Teachers need both substance and

pedagogical training. A powerful tool to develop knowledge and skills

and learn a new teaching style is practical action research concerning

teachers’ own work (Zeihner, 2009.) The concept of knowledge triangle

which Kalman (2016) has analysed is another tool we can apply in

developing education and teachers’ competences as well (Kalman 2016).

Internal networks are very important in pedagogical development at

TAMK. By sharing both good practices and not so good practices teachers

and schools can develop their teaching and learning. The most important

tools alongside externally funded projects are TAMK’s internal

networks, such as the curriculum development team and the quality

development team. The curriculum development team has members from the

schools of TAMK and the idea is to share good practices and to work as

a steering group for curriculum development. Karttunen (2016) stated

that the effectiveness and impact of the work of internal networks

depends on leadership of networks, which has been taken into

consideration. All the leaders and managers have to know the objectives

of the network.

TAMK teachers’ annual development discussions with their superiors

establish their personal development objectives. The aim of the

development discussion is that the personal objectives are in keeping

with the objectives of TAMK. The discussions are also a good

opportunity to get information on the education as well as feedback on

teachers’ work. Based on the development discussions the Development

Unit together with the School of Vocational Teacher Education arrange

training and projects to teachers at TAMK. There is for example a

programme for teachers to develop their pedagogical competences in the

digital environment. In 2015 the digimentors started their work in

every school of TAMK. They are peers who support teachers in their work.

Curriculum development forms the basis for quality of learning and teaching

The curriculum is an important tool

for development. The autonomy of the Finnish higher education means

that higher education institutions are responsible for curriculum

development. In TAMK the curriculum development team with

representatives from the schools works as the steering group for

curriculum development and quality of teaching and learning. The

schools of TAMK organise their own development group which leads the

process in each degree programme. The development process is based on

dialogue between the schools, degree programmes, and the Development

Unit of TAMK, which is led by the vice president responsible both for

internal development and the School of Vocational Teacher Education.

The curriculum development team in TAMK is responsible for:

- process of curriculum development

- application of the objectives for curriculum development

- development of curriculum evaluation criteria

- evaluation of the curriculum development process.

Curricula are approved by the higher

education council of TAMK. Before the approval the curricula are

evaluated by the curriculum development team using the curriculum

criteria of TAMK. These criteria encompass for example the objectives

of curriculum development. During the academic year 2015-2016 the

curriculum development objectives included for example:

- Clearly competence-based curricula which are based on the needs of working life

- The student's learning is the focus

- The student’s possibility to proceed flexibly and effectively according to her/his curriculum

- Knowledge utilisation across the "borders” of different fields of education

- Curricula include descriptions and procedures that allow identification and recognition of prior knowledge and skills

- Diverse learning environments which integrate RDI activities into learning and teaching.

- Digitalization and its influence on learning, learning outcomes and competences

- The international dimension is an integral part of learning and its implementation

- TAMK's strategy and its implementation to practice.

An important part of the curriculum

development process and a part of the annual performance planning

process is analysis of competences needed in working life.

Because the working life is changing rapidly the analysis of the

competences needed in degree programmes is important. That’s why every

degree programme has an advisory board which meets twice a year and

concentrates especially on the needs of working life. In the Tampere

region there is also an education foresight network which collects both

qualitative and quantitative data on the educational needs of working

life. At the national level, education foresights form a part of

education policy and decision-making.

Conclusions

The higher education undergoes a

transition which means that we should update our conceptions concerning

our operations in both teaching and learning environments of higher

education. In such situations higher education leadership and

management are also important tools in supporting the changes and

development. When we live in the changing world and speak about higher

education, we should take into consideration the features of a learning

organisation. This means that we do not only react to the new

information but self-assess and reflect on operations and activities

constantly and use our human capacity to create new knowledge and new

models for operations (Kalman 2016.)

References

- Arene. 2007. The Bologna Process and Finnish Universities of

Applied Sciences. Participation of Finnish universities of applied

sciences in the European Higher Education Area. The final report of the

project. Edita Prima Oy. Helsinki

- Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators – Finland:

http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/education/education-at-a-glance-2015/finland_eag-2015-55-en#page3

- Haukijärvi, I. 2016 Strategizing Digitalization in a Finnish

Higher Education Institution. Towards a thorough strategic information.

Academic dissertation. Acta Unversitatis Tamperensis 2181. Tampere:

Tampere University Press.

- Kalman, A. 2016. Learning – in the New Lifelong and Lifewide

Perspectives. Tampere University of Applied Sciences. Tampere: Eräsalon

kirjapaino.

- Karttunen, P. 2014. Verkostojen johtaminen sisäisen kehittämisen

näkökulmasta. Marttila, L. (ed.) Johtajuuden jäljillä. Näkökulmia

ammattikorkeakoulun johtamiseen. Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulun

julkaisusarja. Sarja B. Raportteja 71.

- Salhberg, P. 2015. Suomalaisen koulun menestystarina ja mitä muut voivat siitä oppia. Latvia: Jelgava Printing House.

- Talvinen, K. 2012. Enhancing Quality Audits in Finnish Higher

Education Institutions 2005–2012. Publication of the Finnish Higher

Education Evaluation Council 11/2012. Tampere. Tammerprint Oy.

- Zeichner, K. 2009. Educational Action Research. pp. 24-42. In:

Schmuck. R. A. Practical Action Research. Second edition. Corwin Press.

A Sage Company. USA.