Entering through the doors of innovation: School visits in Tampere

Owning to the experience provided by

the Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME for short), a

group of Hungarian teachers were given the opportunity to attend TAMK

(Tampere University of Applied Sciences) in Finland between

11-15thApril 2016. As a member of this group, I could visit not only

TAMK but also two Finnish schools, which experience drew my attention

toward the discrepancy of the Scandinavian and Hungarian systems and

school results. In this report I intend to introduce my readers to my

observations and opinion which are solely based on some interviews I

made there and my personal views.

First of all, it is generally true that when people travel abroad, they

tend to compare their own cultures to the host country’s, as well as

they try to point out the most obvious differences. From this

perspective, Hungary and Finland belong to two well-distinguished

worlds.

To start with, as far as I am concern, teacher tourism is not that

prominent in Hungary. Unfortunately, our country has lost its dominance

on the stage of education therefore we have become followers who try to

adapt new methodology and guidelines. It is really saddening but we

must realise that right now we are not the ones who are pioneers in

this field. The reason why I am pointing that out is because I firmly

believe that Hungarian educators must sit back and accept this fact,

and should re-evaluate their methodology and teaching style. I am not

suggesting in any way that the Finnish system is perfect, nor am I

stating that we should copy it. On the contrary, we have to open our

eyes and make a shift in order to be better and more respected. For

these reasons, this pilot programme organised by BME seemed like a good

starting point.

It is not that the Finnish educators are fully aware of the importance

of their great results. When asked, they could really not answer what

made them one of the best. However, they were very helpful and

open-minded during our stay. Our hosts, including Sisko Mällinen and

Jiri Taok Vilppola from TAMK, really made us welcome and tried their

best to let us have a glimpse of what the world calls the ‘Finnish

miracle.’ However, when I write ‘glimpse’ it is really what I mean

since it would have been impossible to become an expert of the Finnish

system within a week. Nonetheless, we could truly understand the

framework and guidelines that shape the Scandinavian education system.

One such framework worth mentioning

is the system itself. Imagine a system where you can have choices: you

can decide what you want to learn and what you want to become. We have

seen this before, you may say, for example one must think about the

English-American systems where students have obligatory and elective

subjects to choose from. In Finland, however, what really fascinated me

was the fact that there were always second opportunities for those who

have made a bad decision or who wished to broaden their horizons. This

kind of attitude truly amazed me because it means that students are not

frustrated and do not live under pressure of their choices, as they

sadly do elsewhere in the world.

Let me tell you an example for that in order to prove my point. During

our stay we had the chance to visit two Finnish schools: a primary and

a secondary vocational school. When entering this latter one, we could

see that the age of students range from 14 to 40+. The headmaster of

Prisma vocational school told us that this was because education is

free and members of the older generations can even earn a monthly state

scholarship worth € 1 000. As a result, generally speaking the Finns

are well-educated and qualified. They are owners of profession

certificates or diplomas provided by state vocational schools or

colleges/universities. This also means that they seek positions that

require high-level of qualification and if they lack those skills, they

can still be accepted with the provision of mastering the required

skills later. Therefore in the school one of the classes we visited

consisted of 12 students, of which 7 belonged to the high school

student age and the rest of them were considered adults. This spectrum

of age groups seemed beneficial in the classroom since the older

students could teach the younger ones and tell them about their

experiences in the field, on top of that, youngers could gain hands-on

experience on what that profession in real life was like. All in all,

this policy ensures that fewer students will make bad career decisions

and those who do can start a new profession immediately after realising

this fact. Not to mention that the number of school-leavers will

probably shrink.

3. A typical Finnish schoolbuilding

with bicycles in front of it and a part of the Hungarian delegation

[3]

[3]

Connection to the modern world is

crucial for them. Not only they were trying to teach real-life skills,

but also let the students and teachers discover the field of their

profession for real. For time to time, students and teachers alike are

required to take part in community work programmes. Students can choose

what profession they want to try for some weeks, while vocational

school teachers must practise in the field they teach at. As a result,

everyone is up-to-dated and students can decide on their future career

more easily. I find it noteworthy that pupils must do mainly physical

labour, and to back this idea up, we were told that the most popular

job among the high schoolers were plumbing because in Finland that is

one of the best-paid manual jobs. Also, when interviewing the students,

they praised this part of the system. One of them told me that he had

spent a summer at a chemical laboratory and this experience helped him

in choosing a career: the 24-year-old boy wanted to become a brewer.

Experience is important and the Finns know that. That is the reason why

they support experience in a field. For example, if a person wants to

become an electrician but he has already worked as an assistant to an

electrician therefore he has some knowledge of the field, he can choose

to be evaluated by a professional committee that can give him credit

points for the tasks he can already do. On the one hand, this is

beneficial for the person because he has to learn less and needs to

prove only his new skills by the end of the course. On the other hand,

the government does not have to finance the full sum of the course

since the adult student will spend less time in the system. Hence older

and more experienced students can get back to work earlier.

No matter their age and skills, everyone was equal in the classroom.

Furthermore, equality was not only a trendy cliché: teachers treated

everyone with the same respect and manner, and students were given the

same opportunities. In general, equality for them means different paths

one must go through. In practice we saw that the students could choose

the topics they wanted to learn, the skills they wanted to master and

when they were ready they showed their products to their teachers. Even

at university the students signed up for courses, picked topics and

areas for themselves and decided on a deadline for them. If they were

successful, they could opt for a new project. However, if their product

was not satisfactory, they could spend more time with it and prove that

they mastered the skill later. This has lead to a democratic,

student-centred system where teachers are only facilitators of the

learning process and students are motivated enough to participate in it.

Even in Finland sometimes it is very hard to motivate students.

However, the main difference between Hungary and the Scandinavian

country is that they are not pushing the kids. For instance, we visited

a primary school lesson where the 10-year-old kids had to learn in

groups of four. There were some boys who did not want to participate in

the task and the teachers let them be. Not because they did not wish to

deal with the boys, but because they realised that forcing them would

lead to nowhere. After around ten minutes, the boys joined the task

willingly and finished the materials on time. Later, we asked the

teachers what would have happened if the boys had not participated and

they told us that the group would not have been punished. If a child is

not ready to take the next step, he will not unless he masters the

skills on his own before the new stage starts. This lenient attitude

was first strange for us but having seen the students working for their

own sake made us realise that indeed in Hungary we do not really mean

student-centeredness for real because we do not really see the students

behind the tasks, nor do we understand their needs.

Every person is different therefore they have different needs. In

Finland, they know this and work according to it. However, there are

some students who need more attention due to their special needs. These

kids are often taught together with the others but get special care

from time to time. Kindergarten teachers have to spot these kids and a

board later decides what steps are to be taken. Early recognition

results in better chances of rehabilitation. When entering the primary

school, the students’ records and reports are sent to the schools which

can take care of the students with special needs.

Every learning group has a teaching assistant who follows the group

from lesson to lesson. The subject teachers have their own rooms with

the books the students use, their own kitchen and teacher’s corner for

personal space. In front of each and every room there is a table for

the extra skills development sessions. When a group and its assistant

enter the classroom, the teacher can decide if some children need

special care. For example, if a child has reading difficulties, she or

he may decide that the student will spend some of their time in the

corridor by the special desk with the assistant. It is important that

not the entire lesson is to be spent there therefore the child will not

feel isolated from the group. It seemed that kids take turns and the

ones who are better at Mathematics were given extra lessons of the

English language and vice versa. Due to this measurement, no child is

left behind. After all, every child has special needs according to the

Finns.

4. A typical corridor, in the

foreground the desk for special education sessions, own photo

The obligatory education in Finland

ends with primary school. However, elementary school education – unlike

in Hungary – is nine years long. After it, students must decide whether

to start working without qualification (because they want to achieve it

later), or to go to secondary vocational or grammar school. We were

told that based on the statistics, half of the students choose

secondary vocational education, and 50% opts for grammar schools. Those

who cannot make up their minds can stay for a 10th year during which

general skills development lessons and career guidance take place.

There are no entry exams: students only have to apply for a school

major and they will be granted it provided they have recorded the

proper skills development. Students and teachers do not need to travel

long distances given the fact that each and every school has the same

quality of education, and each city education board offers almost the

same profession palettes.

Another idea worth mentioning is the environment. In Hungary, we can

state that most of the school buildings are in average condition,

however, most schools are not properly equipped. In Tampere, the

schools we visited were very well-equipped. Besides, all equipment was

available by the students as well. Free Wi-Fi connection was provided

everywhere and the kids were online all the time. Since our Finnish

colleagues know this, they have decided to turn this phenomenon to

their own advantage: it was not special to ask the kids during the

lesson to use their mobile phones or tablets and search for online

information. Using the telephone was allowed during the lessons no

matter what the students did on their phones. Obviously, we could sense

that not every teacher was happy with this policy, however, even them

were willing to give online tasks for the pupils. For example, during a

lower primary English lesson the teacher used the technology for

teaching the group the proper pronunciation of the English alphabet.

What is more, the use of digital materials was evident from the

beginning and one of the teachers told us that students own only a

handful of books because the school provides them with everything, even

with tablets full of digital materials.

Technology, however, is not most important thing that got my attention.

What I enjoyed the most was the fact that seemingly there was no

schedule the teachers or students were holding to. Everything seemed

changeable and not fixed. Even the furniture was not only portable but

also convertible. The chairs, the desks and even the boards were mobile

and sometimes we could see how easily a teacher changed the environment

to fit the needs of the students or the lesson.

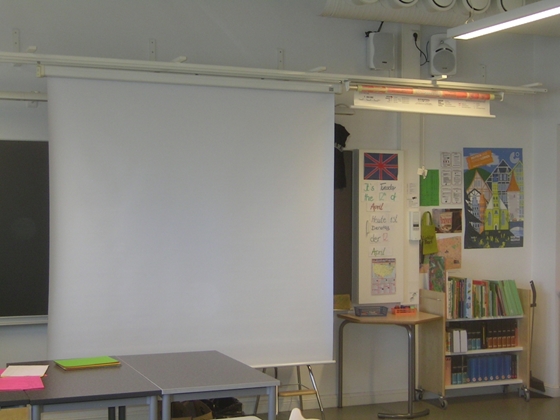

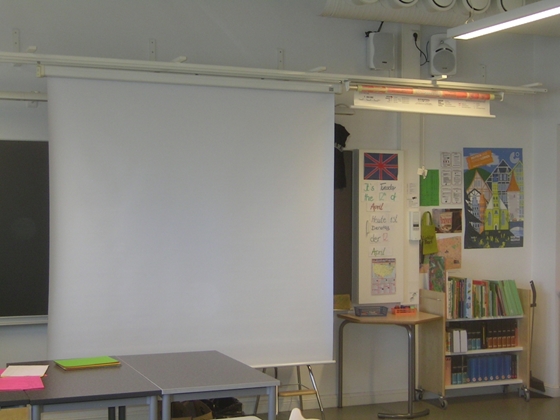

5. A portable classroom

[4]

[4]

This mobility also supports the

notion that not the material but the people who take part in the

learning process should be in the focal point. The classical

‘aeroplane’ style of seating arrangement does not fit every lesson and

it can happen that a project needs more space.

What is more, who says that learning should take place solely at

lessons? While wandering through the corridors, from the windows we

could see some students in the schoolyard who were measuring trees.

When we asked them what they were doing, they told us that their

Mathematics teacher asked them to measure the diameter of the trees

because of a project. Later we were informed that every child must

finish a school project each and every term. The projects are

multidisciplinary and usually take at least a week to complete. For

example, when the group enters the Forestry project, they learn about

trees in Biology, go to the nearest forest to draw some pictures of

trees in Arts, learn and write poems in Literature and create wooden

chairs in Crafts. During that period of time, everything is in

connection to the theme after which the students must perform or show

their skills.

6. A project on global warming, own

photo

This kind of teaching is similar as

of the alternative teaching programmes in Hungary. The difference is

that they do not teach in this style all year around therefore when

project weeks come, the students are really looking forward to them.

They even organise performances or exhibitions based on their projects

to which they invite their parents, the city governor and the members

of the local education board. They even appear in the local news.

Students participate because they feel motivated and involved. The

teachers know that the students will do their best given the fact that

they want to perform well. This system, as we can see, is based on

trust which was evident wherever we went. During our talks with the

educators, it turned out that in Finland no testing takes place. The

first test students encounter is the Matura examination. Of course,

students are evaluated – but by themselves. After lessons students have

to fill in a short questionnaire and answer some basic question about

their performance. Teachers record those notes and add their own

suggestions. Students and their parents alike can read the reports so

together they can decide on the best way to develop the pupil.

Not only the students are not tested, but the teachers are not

evaluated, either. In Finland, the teachers are among the best-educated

and most respected people, and the government accepts this fact. There

is no supervision and the teachers are given freedom. The national

curriculum was written by 300 teachers and contains only 10% of the

school curriculum, so the schools and teachers can decide what they

want to do. In this respect, the teachers do not feel oppressed or

forced to focus on topics just because those are obligatory. Moreover,

if a teacher is trusted to choose their own materials, they will teach

that with pleasure which is beneficial in long term, given the fact

that burning-out might be avoided that way.

The word trust is essential here. In Hungary, we do not trust our

students. We test them, we give them daily homework because we do not

believe that they were capable of learning on their own, we choose the

materials ourselves because we do not feel they could do that. We

hardly ever give them freedom because on the one hand, we were

socialised that way, and on the other hand, because we are never given

freedom, either. Unfortunately, in Central Europe teachers are the

slaves of the system in a way that they are oppressed.

However, some questions arise. Is it only freedom that matters? Would

the system be better if we were provided with more choices? Could we

motivate the students more? These are very hard questions to answer.

However, the truth is that based on what I have seen, the answer is

maybe. With time, we could get to the point where the participants of

education are trusted. Until then we can buy the fanciest equipment,

print the most flamboyant books and develop the best digital materials,

there will be no changes because in Hungary school is a must and not a

great place to be.

Teaching takes at least two: an

educator who wants to teach a new skill and a student who wants to

master that skill. The whole teaching process should be based on mutual

trust and cooperation. In an ideal world, the student would tell us

what skill they needed to develop and we would decide together how to

do that. We should not teach them as the original sense of the word

suggests, but must facilitate and monitor the progress and report back

on the development. However, it is the student only who could decide if

she or he has reached the aimed target in skills development. Not the

teacher, nor a standardised test. After all, she or he should be the

beneficial of our work.

At least this is what this project

has taught me, and for this experience and realisation I will forever

be thankful for both TAMK and BME.

[1] TAMK logo [Online].

http://www.tamk.fi/web/tamk/etusivu |Last dowloaded: 11/18/2016.; BME

logo [Online]. https://www.bme.hu/ |Last dowloaded: 11/18/2016.

[2] Pictures were downloaded from:

https://fi.linkedin.com/in/sisko-m%C3%A4llinen-16395966 and

https://plus.google.com/106893713836757145819 |Last dowloaded:

11/18/2016.

[3] Photo made by Ágnes Judit Presér, published at

http://hvg.hu/itthon/20160415_finnorszag_kozoktatas_tampere _okostabla

| Last dowloaded: 11/18/2016.

[4] Photo made by Ágnes Judit Presér, published at

http://hvg.hu/itthon/20160415_finnorszag_kozoktatas_tampere _okostabla

| Last dowloaded: 11/18/2016.