Various Challenges of Science Communication in Teaching Genaration

Z: an Urgent Need for Paradigm Shift and Embracing Digital Learning [1]

„Back in my time!” – Instead of

Introduction

„The children now

love luxury. They have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show

disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise.”

/Socrates, 469-399 BC/

As the intentionally provocative

quote shows, Socrates was dealing with the generational conflicts

already two and a half thousand years ago. although ancient Greece was

featured by cultural productivity and economic prosperity (Hall, 2007)

The period when the philosopher lived can be considered as the dawn of

classical Hellenic civilisation: that time the Athens society was not

suffering of crisis of values, the life of the inhabitants of the

polises was organised along solid moral conventions. Despite of this

Socrates named Greek youngsters as a frivolous gang. The

dissatisfaction of adults towards teenagers – irrespectively to the

socio-cultural environment and ideology – occurs in social history from

time-to-time.

[2]; In this respect humanity seems

to be a homogenous

group, since it can be sensed as a general tendency that the following

generation is held liable for any changes experienced on the field of

human cerebrality. “Back to my time” – say our grandparents; this sigh

shows implicit valuation and accusation: as if everything were better,

more accepted, more „normal” in their youth. And who else could be

liable for cessation of “normality” than the youth breaking up with

morals and traditions?

This study does not intend to deal

with this subjective and hard to evidence scheme of thinking. Rather it

tries to call attention to that the success of handling the problem is

definitely influenced by the knowledge on the factors behind the

phenomenon and the ongoing reinterpretation of the definition of

„normality”. It is not a secondary standpoint at all whether the

changes to the attitude between generations - different

characteristics, skills, competencies – are identified as deviancies,

taken out from their context, or they are considered as borderline

between sections and handled as a possibility offering new perspective.

(Ng et al., 2010)

In my study I am reasoning for that

since adoption of changes, tolerating and teaching each other are key

elements of coexistence of different age-classes (West et al., 2002),

it is reasonable to find the way for bringing the new possibilities of

youngsters to the surface, for teaching them, and use their different

competencies for the benefit of the development of the society. To

achieve this the older generation is required to be open to digital

catch up (Kolin, 2002), while they should not condemn the values of the

youngsters and they should not prevent fulfilment changed of demands

for obtaining knowledge. According to my thesis from the

perspectives of economic, educational, political, labour market and

cultural challenges of our days, recognition and conscious application

of the possibilities hidden in mutual assistance and transfer of

skills, viewpoints and experiences are unavoidable. Therefor in

everyday life – moreover in pedagogical work – it is vital to find

response to the following questions:

- Is the way of thinking and behaviour of the younger generations

form basis for worries indeed?

- What are the main reasons of causing changes between the

generations; who or which processes can be held liable for the

transformation of values and attitude?

- How did we handle these changes, how do we face the challenges

resulting from such changes?

The study analyses these topics,

primarily approaching the characteristics of generation Z deviating

from that of the previous generation from science communication and

educational aspects. Based on international and Hungarian research the

paper gives brief review on the impact of our current time, the

development of information society and technology on the world view and

discrepancy of the different age-classes. I attempt to identify those

characteristics of transferring knowledge, consumption and media usage,

which are definite to development of the relation of persons born after

1995 to science, then I summarise the models of Public Understanding of

Science (hereinafter referred to as PUS)

[3];

relevant to generation

Z. In the second part of this study I reason for paradigm shift in

formal education and I give recommendation on the methodological

framework of a progressive educational system, which is able to

successfully meet the demands of the analysed age-class, and which can

play a definitive role in forming the interest in science and

preparedness of the digital generation.

Coexistence of Generations in the

Information Society [4]

Formation of the information

society has completely rearranged the access to the social

resources and information (Beniger, 1986), what has significant

technological, economic, employment and cultural aspects (Webster,

1997). While in the industrial era the devices and natural

resources were definitive, nowadays knowledge provides the majority of

the produced and consumed goods, the work defined by information

processes become definitive versus the direct physical work. (B. Tier,

2014) The development taken place on the field of information

processing, storage and transmission on one hand led to wide scope of

application of digital technologies, while on the other hand to the

convergence of telecommunication and IT in all segments of the society.

In the 2000s technology forms each

and every segment of our life; accordingly it exercises a formerly

unknown extent of stimulation and information pressure on the society

accompanied with acceleration generational differences. (Rückriem,

2009) The structure of the world has become network-based, where

internet, information technology and telecommunication have turned into

a faith defining experience of the younger generations. (Castells,

2006) This process not only detached the younger generations from the

traditional, direct human communication media, but it has

substantionally changed their relations, cognitive and learning

methods. (Nyíri, 1999) Digital experience, network-based interaction

and unlimited communication have become a basic experience and daily

need of those born on the turn of the millennium. (Castells, 2006) the

value of knowledge and media, and knowledge vital to self-maintenance

in the knowledge society built on lifelong learning intruded into the

expediential values. (Gergátz, 2009) Therefore the borderline between

childhood and adulthood is less sharp: a child browsing the internet

consciously makes his way in the same media as an adult; this results

in interflow of the scope of entertainment and work. (Nyíri, 2004)

It is an elemental principle of

sociology that each and every generation lives history in its own

characteristic way: the events and features of the era get built in its

identity. (Howard, 2000; Urick, 2012) While formerly the generation

forming impacts were nurtured mainly by history, nowadays they rather

start up from the direction of technological development. (Csepeli,

2006) While – on the contrary to the former technologies – the

technology of the information society has deeper and more comprehensive

impact on our life, thus the distance between the approach of younger

and older generations, between the “old” and the “new” is growing.

(Gergátz, 2009) Basically this is the main reason of the generation

gap; and this is what initiates the generations to start conversation

with groups maintaining other identity.

Considering that the newly appearing

mechanisms of obtaining knowledge has totally transformed the relation

of the new generation to the world and the former generations (Combi,

2015), from the 2000s identification of the reasons of the conflicts

between the generations and specification of the general

characteristics of the different age-classes are the most important

tasks of generation research. (Masnick, 2013) in the course of

developing the methodology, in addition to exploring the phenomena,

finding the practical aspects of the generational conflict, and

selection of the methods for problem management successfully serving

social interests are also important viewpoint. (Lengyel, 2003) Yet

before giving exact methodological recommendations on alteration of the

former education system, in the next chapter I define the generation Z

and I will briefly describe its relation to technology.

Media Usage of the Digital Natives,

their Characteristics and the Technology

The basis of generation research is

that the certain generations have different so-called cohors

experiences – characteristics defining the attitudes of the persons

born at the same time and similar needs. (Simon, 2007) Due to the

different socio-cultural background the common experiences and values –

join the members of a given age-class in a loose, but definitive way.

Despite heterogeneity e definitive trend can be observed along the

formation of value preferences; this provides possibility for the

social scientists to connect individual decisions and identify the

differences between youngsters and elder people. (Pilcher, 1994)

Although the literature related to

the field of science is not uniform in respect of the terminology for

different generations and dates of birth, the majority of research

deals with analysing primarily the Baby Boomers born between 1946-1960

(Howe & Strauss, 1991; Landon, 1980; Owram, 1997; etc.), generation

X born between 1960-1980 (Miller, 2012; Markert, 2004; etc.),

generation Y, also called millenary generation, born between 1980-1999

(Horovitz, 2012; Strauss-Howe, 2000; etc.), and generation Z, also

called iGeneration, Pluralist or Digital Generation, bringing up the

most of interdisciplinary problems nowadays, born after 1995 (Horovitz,

2012; Turner, 2015; Dupont, 2015, etc.)

[5]; Since

this study

approaches the impact of information society on the characteristics of

generation Z deviating from those of the former generations from

science communication and educational aspects, I will discuss more

detailed the characteristics and media usage of the ones born at the

end of 1990s.

Generation Z is a new type generation; either in its content

consumption, socialisation or identity the developing

info-communication technology plays a significant role (Ipsos MediaCT,

2013) According to the findings of a Hungarian research

(TÁMOP-4.2.3-12) analysing the costumer behaviour of young people aged

15-25, this age-class spends 5-6 hours daily with use of media;

basically the use of mobile carriers, smart phones and tablets is the

most typical (Ipsos MediaCT, 2013), while in media usage at home the

dominancy of computers can be observed. (Guld & Maksa, 2013)

Popularity of these devices can be related to the Internet: from the

web 2.0 applications available through the network the social sites,

blogs, video sharing sites, chat programmes, news sites and file

sharing sites are the most important. However, classical mass

media were not crowded out from the daily routine of young people, yet

their role was revaluated and their consumption has become more

superficial: radio and television can be related to background media

usage, while the loss of importance of newspapers and magazines is

reportable. (Guld & Maksa, 2013) The members of generation Z set up

the world surrounding them via mutually edited contents, shared info

and comments; they take part in discussions catching their attention

assertively and actively. (Tari, 2011) Of course not only they form the

environment, but also the environment is greatly forming the cognitive,

affective, conative and social senses, daily routines and social

relations of the ones born after 1995. (Tari, 2011) As a consequence,

while in the life of former generations the real offline and online

presence existed marginally separated, for the first global and digital

age-class these two things are harmonically joined: technology

interweaving the entire life and being permanently present has

become one of the most important device of expressing ones identity.

(Ujhelyi, 2013)

The Basic Problem of Educating

Generation Z

From the viewpoint of science

communication the basis of successful education of generation Z lies in

the professional discretion that its members – on the contrary to

generation Y or X – did not start to adjust to the digital word in a

certain section of their life on the effect of professional pressure,

but they were born in a dynamically changing environment, which offers

the most developed hardware and software solutions to resolve everyday

problems. That is why Mac Prensky calls this age-class as “digital

natives”, whose demand on receiving information has changed

pragmatically. (Prensky, 2001:1) The brain of the members of generation

Z has not only developed in a different way than that of their

ancestors (Trunk, 2009), but due to the frequency of their interaction

with the environment they also process the information differently

(Presnky, 2001). While the older ones adjusted to the changing digital

environment through individual learning mechanisms, generation Z has no

learning “accent”, its members speak “digital language as their native

language. According to Prensky the teachers and researcher who are

active in our days can rather be considered “digital immigrants”, since

they are learning the new “language” only now.

[6];

(Presnky, 2001:2).

Thus generation Y or X in a certain extent unavoidably lives in the

past: it will be only an umpteenth idea of its members to refer to the

new technology whenever they need solution and they adapt the phenomena

of the digital world less naturally than the ones born at the end of

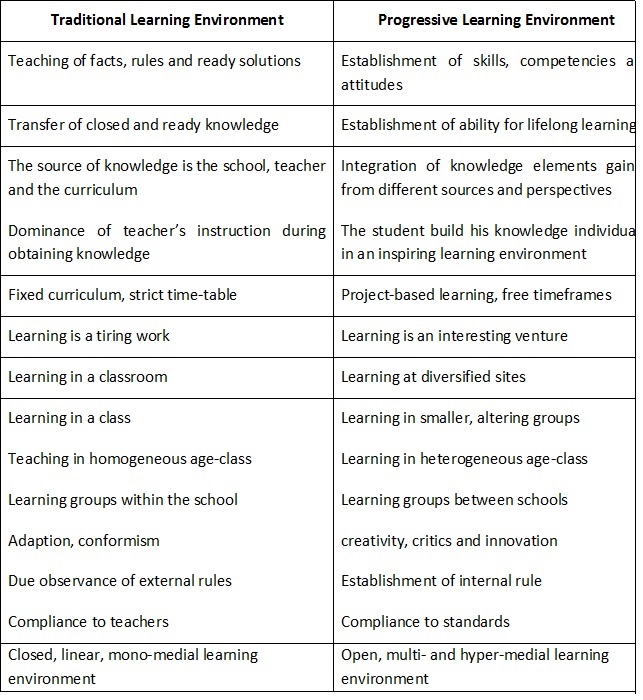

‘90s. (Prensky, 2001) For illustration of the conflicts influencing the

education in its entirety I use the below chart of Kristiansen

(Kristiansen, 2011), which schematically compares the different

characteristics, skills and competencies of the digital immigrants and

the digital natives.

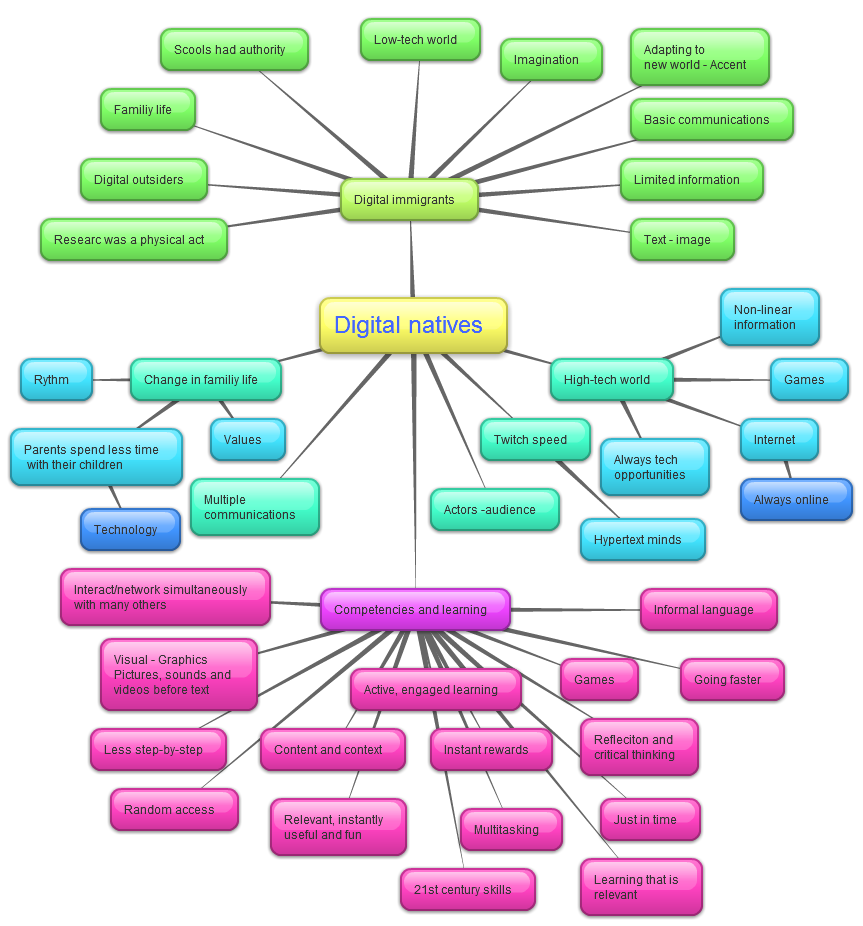

Figure 1 – A Thinking map of Digital

Natives

The conflict resulting from the above

chart – supplemented with the paradox situation that as regards to

great basic formulas the society can already be considered as

information society, yet the superstructure of public education still

follows control structures of the industrial era (B. Tier, 2014) –

represents one of the greatest problems of science communication. Since

the digital immigrants – who in their own time learned slowly,

coherently, individually and profoundly – are less rewarding to those

new skills which the natives naturally own resulting from the everyday

interactions. (Prensky, 2001) If we add up this with that the scope of

expertise transformed due to the structure of knowledge society, the

ratio of mental workers grow on the labour market, and the significance

of skills related to information and communication technologies (ICT)

(Hinrichs, 2000), the urging need of reworking the education becomes

evident. In the 21st century emphasis is placed on fast, accurate and

productive work: increasing complexity of the tasks expects creativity,

flexibility and ability for team work from the youngsters becoming

professionals in the 2010s. (Cisco, 2009)

Changing demands for learning

When finding any problem to be

resolved the “dotcom” kids living in virtual community already to not

expect response from pedagogues and schoolbooks which were formerly

considered as primary source of knowledge, but – since they have

natural skills to operating telecom devices, excellently navigate on

the internet and easily establish relations – they get solution from

each other or browse the internet to seek for it. (Duga, 2013:3) This

is also supported by the EU Kids Online I-II research: the time spent

with browsing the internet by the young generation is not spent only

for entertainment, communication and consumption of contents, but,

subject to the type of the tasks their presence on the web promotes the

process of learning as well. (EU Kids Online II., 2012)

Also Dunkels and Zipernovszky discusses the possibilities of learning

via internet in details; their research discovers that social sites,

such as Facebook, Skype, LinkedIn, or Google+ offer new forms of

learning for common work. (Dunkels, 2007; Zipernovszky, 2008) Besides

social sites the microblogs – Twitter, Tumblr –, and also the video,

photo or sound sharing sites , such as Youtube, Picasaweb, Flickr,

Ustream or iTunes are also popular. Generation Z uses presentation

applications, such as Prezi, Slideshare, Googledocs, etc., as well, but

on the contrary to generation X or Y also the use of different

framework systems, online learning communities and virtual environments

are not unknown to them. (Duga, 2013:11) There are several reasons for

what the sites are successful; on one hand the “hyper” mass of text on

the web stimulates the natural, individual learning, the process of

obtaining knowledge resulting from instinctive curiosity and internal

motivation without the control of any professional. On the other hand

it improves both logics and collective informal learning, what is based

on permanent exchange of experiences featuring the virtual communities.

(Duga, 2013:6)

The ones born at the end of 1990s actively create informative contents,

since they prefer multimedia communication to written texts;

accordingly also their processing methods are non-linear. According to

a survey of the Budapesti Üzleti és Kommunikációs Főiskola the members

of generation Z - primarily resulting from the speed of search drives –

prefer the fast obtainable information (HVG, 2014), they like to see

the result of their work immediately and expect instant feedback.

Interaction and empathising experiences are important to them. They are

able to deal with several things simultaneously and they are effective

in organising their work, they get the information what is in their

interest in diversified channels and quickly. (Bessenyei, 2007) At the

same time the survey also highlighted the processing of longer text and

verbal restoring of the knowledge text cause difficulties to them; they

consider the lessons supplemented with spectacular visual elements as

easier to remember. One-direction communication causes problem to them,

therefore they find it difficult to follow theoretical deductions and

tangible, practical examples are important to them. (NOL, 2014)

Thus technical development has greatly changed media usage and

characteristics of the digital natives, what led to a more and more

defined student-attendee requirements and transformation of values on

the labour market, while this has impact on the educational system as

well: members of generation Z require substantially different methods

and curriculum. (Jukes & Dosaj, 2006) Moreover the gap between the

capacity hidden in the digital generation and the available

professional, device and solution environment is growing (Z. Karvalics,

2013), this gap gives new tasks continuously to the ones wishing to

modernise the formal education. Before oi start to discuss the

particular professional aspects of the science communication conducted

with the ones born after 1995 and my methodology developing

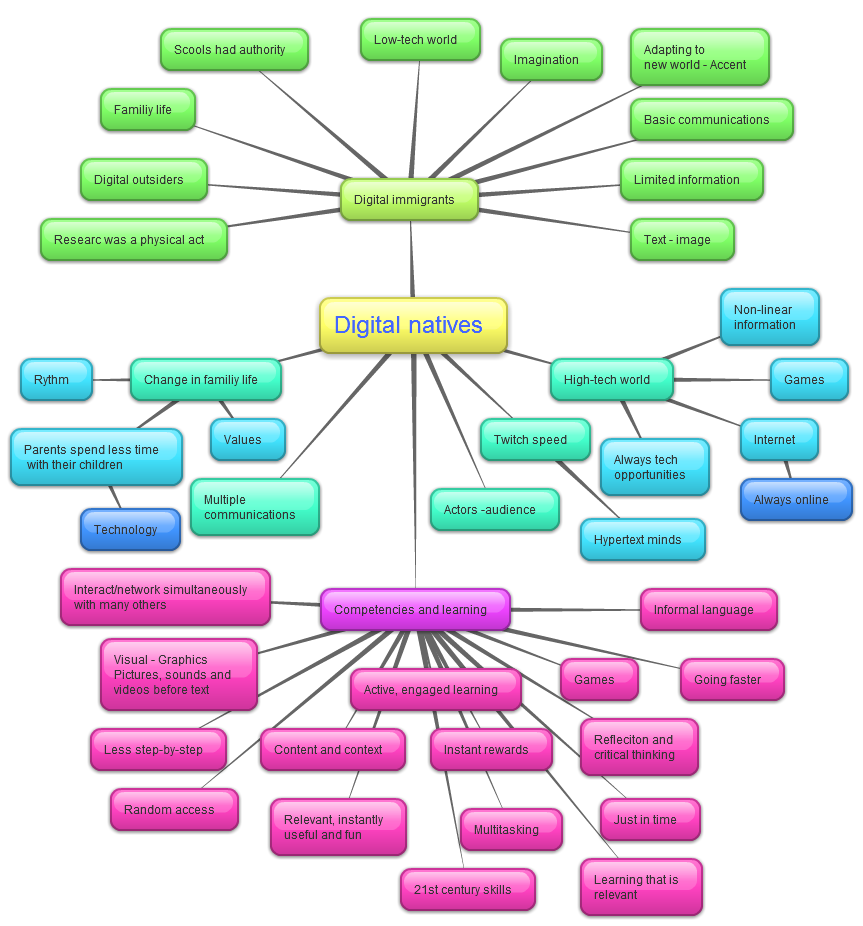

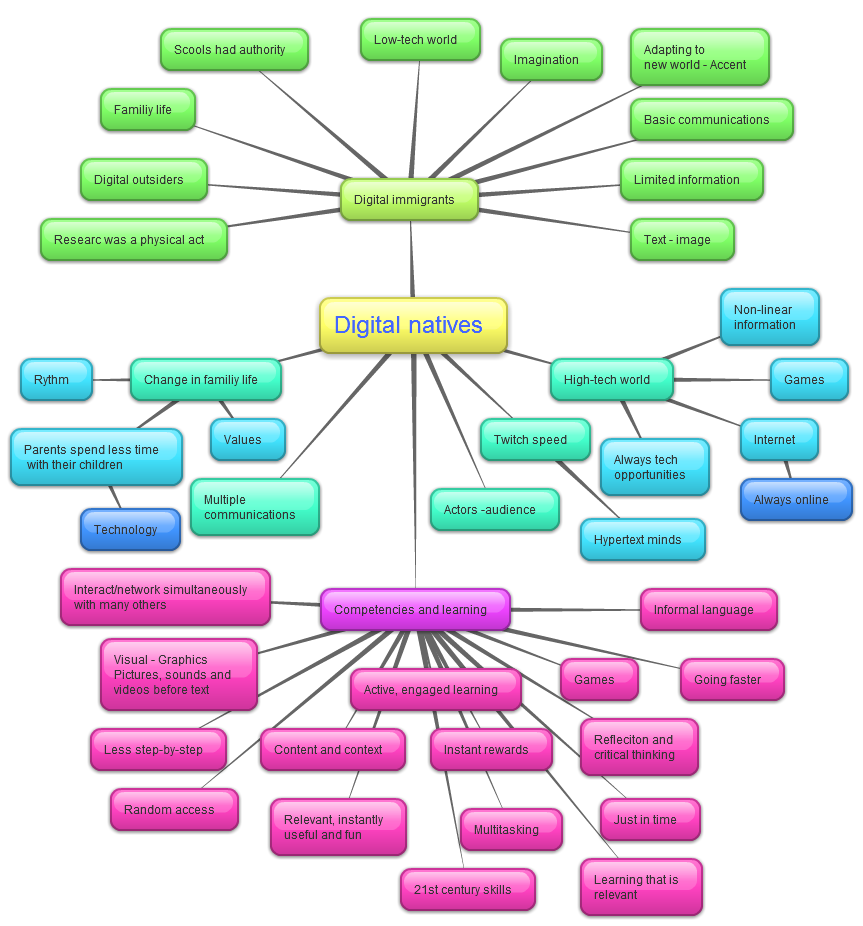

recommendations, I summarise the aforementioned based on the table of

Jukes and Dosaj (Jukes & Dosaj, 2003), particularly the major

differences between the digital immigrant teachers and the digital

native learners.

Table 1 – The Differences between

Digital Native Learners and Digital Immigrant Teachers

The gap between the competencies of

students and solution environment of schools

Due to the changing learning demands

of generation Z the importance of the role of internet and digital

technology in education is unquestionable nowadays. Internal learning

motivation features the self-development of the members of this

generation, their interests are diversified, what is reasoned by that

an enormous quantity of impulse influence them since the day they are

born. (Turner, 2015) They are attracted by several scientific – mainly

technological – topics; they seek for them more purposefully than those

borne before the ‘90s. Their approach to learning, getting informed and

to knowledge itself has also radically changed. (Oblinger &

Oblinger, 2005) An increasing ratio of their knowledge results from

other media than schools: beginning with different traditional media,

through museums, scientific festivals to meetups, events popularising

science and other non-traditional science communication sites.

[7];

Although the so-called edutainment, i.e. obtaining knowledge in an

entertaining form is an important demand on their side (Demers,

2005:143), yet they are critical users of media, they avoid

advertisements and are aware of the general hazards of media. In their

knowledge obtaining mechanisms they prefer simultaneous interaction and

relevant, promptly usable knowledge having practical significance.

(Bessenyei, 2007)

These changed generational characteristics result in that an effective

education must revaluate its current situation, it must consider that

from the several learning environments it represents only one – and not

even the best – option, and that science communication must adjust to

the cognitive changes going through in the mind of youngsters and their

consumer demand, also in its methodology. As the today students are not

the same as the ones for whom the current education system was set up

(Prensky, 2001), therefore in the education of generation Z it is vital

to establish an environment and information channels, where development

similar to that unnoticeable learning of their childhood can be

implemented. (Papert, 1996)

As the Netgeneráció 2010 international survey reveals, since the

members of the age-class get to resolution of problems individually,

not on a uniform and previously defined route, the educational

institutes must review the input and output requirements an carrier

milestones set up for the students several decades earlier. (Hartyányi,

2010; Anderson 2011:126) The traditional basic skills – writing,

reading, counting – were added up with several new kinds of skills, the

development of what would be worth to be inserted in the curriculum.

(Z. Karvalics, 2014) The key to generation Z’s understanding of science

is the development of dynamic, colourful, creative projects providing

the joy of success through partial results. I improving the learning

attitude of the age-class – besides visualisation – involving the

students and cooperative methods allowing more effective transfer of

knowledge also have important role. (Fehér & Hornyák, 2010)

What model should be followed to

educate students born after 1995?

It is a fundamental principle of

political economy that scientific and technical knowledge is the main

drive of social development: without up-to-date information the

knowledge of human civilisation could hardly improve. As it is also

shown in this study, accurate definition of knowledge is not easy,

since it units not only epistemological, philosophical, pedagogical,

psychological and economic viewpoints, but the term seems to have

different meaning for the different age-classes. As a general

definition it could be stated that knowledge is the mass of

systematised gnosis created about the world surrounding us, obtained

mainly by experience, accumulated since the dawn of civilisation and

transferred from generation to generation. A kind of product, what has

clear, but not always quantifiable values, and as such it is

marketable, i.e. can be understood along the rules of market demand and

offer. (Palugyai, 2012)

In case the characteristics of generation Z are also taken in

consideration the above definition requires a plastic timely

interpretation: the world surrounding us is continuously changing, and

these changes impact us as well. Due to the use of info-communication

technologies the ones born at the end of 1990s understand knowledge

“obtained by experience” in a different way than generation X or Y,

moreover the labour market, which is getting digitalised considers

expertise on other fields as marketable than before. One of the

characteristics of the knowledge-based society is that in order to

successful self-assertion its members must face the mass of information

surrounding them, and must become able to select and find the

relevant information (Molnár, 2008), than apply the knowledge

obtained this way properly for their purposes.

[8]

The continuously expanding mass of information from the information

boom and appearance of the new type students represent a great

challenge for the existing knowledge systems. Since labour market

integration and everyday decisions of generation Z is significantly

impacted by the quality of education and the channel of scientific

interaction, it is worth that pedagogues, scientists and curriculum

developers to give up on the former teaching methods and work out such

training and information transferring and educational environment,

which are customised to the requirements of this generation. (Oblinger

& Oblinger, 2005) On comparing the differences in methodology

of educating generation Z and the traditional teaching paradigm, it

occurs that the ones born before the 1990s obtained their

qualifications fixed to a place, based on fixed teacher and student

roles. Education of generation X or Y was primarily based on

transferring universal, fact-focused, isolated masses of knowledge and

summative valuation, while the cognitive tools of the students

characteristically included memorising and subsequent recall. (Brown,

2005)

Public Understanding of Science uses the term Deficit model for this

one-direction information transfer, what was formed based on the idea

that the head of everyday people is empty. According to this model

scientists and teachers can be considered as the main source of

knowledge, they are the umpires to decide on what extent it should be

intermediated to the audience, the students. This situation leads them

to a clear action programme: their task is not else than “fill those

heads”, i.e. teach the possible most science to the students, the

laymen in order to improve the social opinion on science. (Gregory

& Miller, 1998:11)

As also the researchers of science communication admitted in the ‘90s

this model failed at three points. Firstly, when the information is

questionable within the science community, thus is in the course of

formation. This is a problem primarily because the knowledge required

by the society – especially by generation Z – less belongs to

theoretical physics, history or biology, but they are rather

conceptualised on the level of everyday practical decisions, e.g. on

the technology being continuously “on the conveyor-belt” or on the

field of medicine what is accompanied by passionate professional

disputes. (Harlick & Halleran, 2015) Secondly, the Deficit-model

discusses the scientific problems without defining the context, what –

as we have formerly seen – is a basic factor of the interest of

generation Z.

[9]; Thirdly, the digital generation rather demands a

custom-made science communication adapting the changes of the world,

offering abundance of possibilities and based on interaction, than an

outdated pressurising education model, which is rigid and independent

of the technological environment. (Brown, 2005)

Instead of isolated facts generation Z requires the joy of discovering,

micro-level understanding and knowledge embedded in context. Since

“information” and “knowledge” do not mean the same: Knowledge is

information understood in its context. (Nyíri, 2004) Therefore this

age-class prefers diversified relations based on mutual cooperation

instead of fixed roles. It takes teachers as experts or mentors; it

seeks flexibility and diversity also in the educational sites, devices

and calling for account. (Brown, 2005) PUS also built this age-class

specific need and the critics raised against the Deficit model in its

methodology; its second model already considers that the meeting of

science an publicity takes place embedded in everyday situations,

socio-cultural and technological environment, thus also the scientific

interest of laymen takes is aligned to the entirety of the problems

related to finding guidance in the world. According to the Context

model the head of people is full of strategies for obtaining knowledge;

primarily they do not seek general education, but need scientific

expertise in exact situations requiring decision. (Gregory &

Miller, 1998:88) According to this approach the aim of education is to

establish common forum for scientific and everyday interests, i.e.

building out high quality and up-to-date relation between the science

being prepared – and not only in terms of schoolbooks – and the

youngsters. (Pintér, 2015) According to Hamza & Wickman the

learning in science need to be approached more as a contingent process

than as something that progresses along one particular dimension. They

show “how students appropriate the sociocultural tools of science and

how how they situate what they learn in both the particular features of

the activity and in the relevant science.” (Hamza & Wickman,

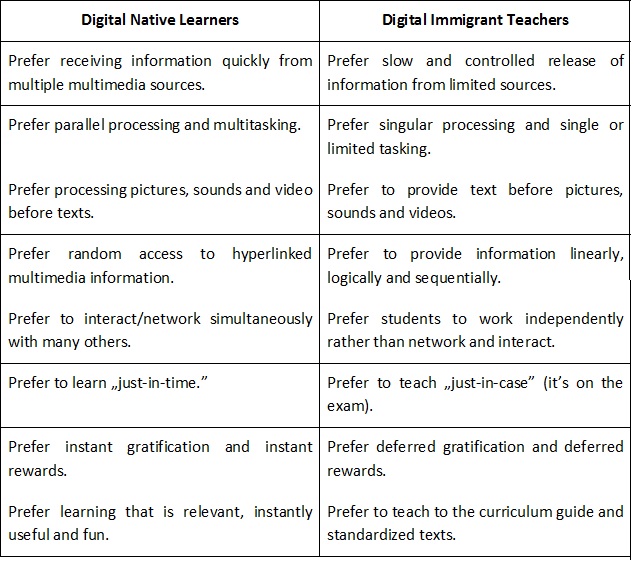

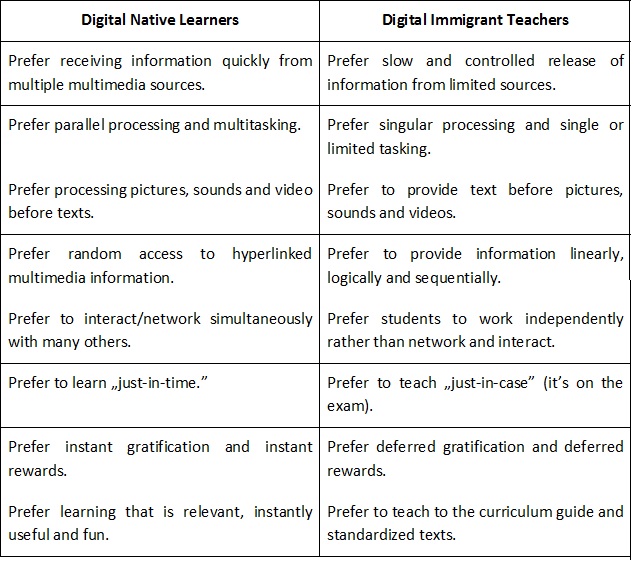

2013:113) The below table shows a summary of the differences between

the traditional learning and teaching paradigm and the two science

communication models. (Brown, 2005: 12.6)

Table 2 - Differences between the

Traditional Learning and Teaching Paradigm

As it is shown in the above table

science communication must be an ongoing reconciliatory process, and

teacher must give up on one-direction information transfer and the idea

that they have no other task than fill empty heads. (Gregory &

Miller, 2006:199) If we also add that through their impact on the life

of publicity the results of science are becoming more and more social,

it becomes understandable that it is vital for the pedagogues to adjust

to the requirements of laymen and they should openly face the

possibilities of science communication and its practical limits.

Accordingly information must be intermediated to generation Z on

routes, which take the social and technological factors and the

knowledge the students originally possess into account.

[10]. (Gregory&

Miller, 2006:203)

According to this study science communication is able to promote the

undertakings of laymen in the disputes in course on the field of

science or in political decision-making related to science, only in

case it is customised to the generation and embedded in context.

[11];

Although generation Z primarily has no demand for engagement in respect

of public life, but in respect of education, raising interest of its

members towards scientific news and disciplinary literature is the most

important task of pedagogy. As science consumption of the

net-generation is more pragmatic than that of the former generation, in

addition the socialisation of the “digital immigrant” teachers and the

“digital native” students resulted in different view of world,

therefore it is reasonable to see education as a mutual recognition

process; as a dynamic exchange-mechanism, in what social groups of

different attitudes and different needs take part. (Gregory &

Miller, 2006:203) In this dialogue confidence and trust are key factors

(Smetana et al., 2016: 89), and in order to this all age-classes must

be open, ready to assist and compromise with the different

generations. Progressive education can hardly be implemented

through authoritarian statements of facts, declarative transfer of

knowledge and punitive call for accounting. (Gregory & Miller,

2006:204)

Tasks to be completed in order to

establish a progressive education system

As the research findings summarised in this study show, the educational

and scientific institutes must examine how they can adjust to the

changing demands of the generation and their customer behaviour. (Duga,

2013) Science communication conducted with the digital generation can

be successful only in case it builds – besides exploiting the

technology – on flexibility in time and space, teamwork, diversity and

the already existing knowledge and activity of students. (Harlick &

Halleran, 2015) In order to make education progressive it is vital that

the teachers and students shall set up partnership, what is based on

respect shown for each other, to facilitate placement of

competency-based approaches in the forefront against the content-based

approaches. (Duga, 2013)

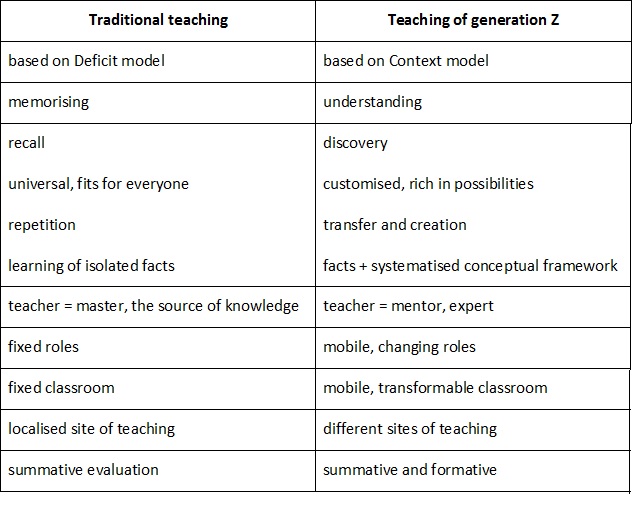

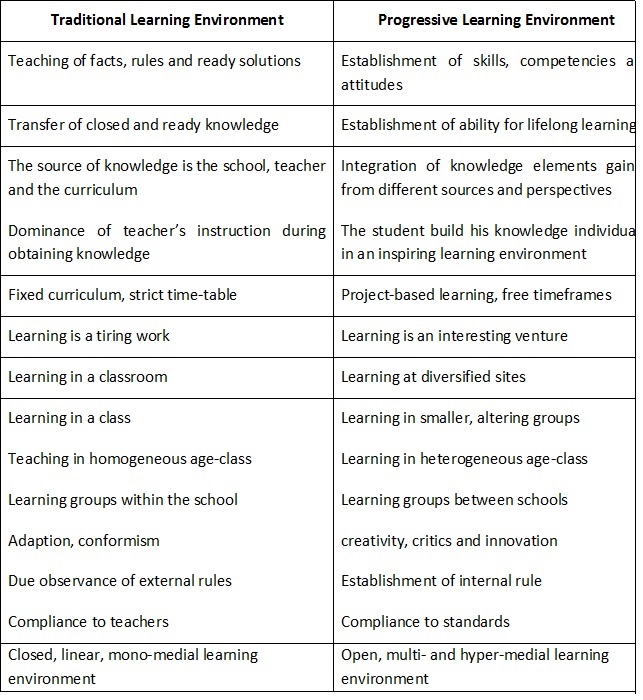

While the traditional model apostrophes learning as a work done with

sweat and along facts and curriculum fixed to rules, obtained according

to strict time-table, the progressive learning environment provides the

experience of integration of knowledge elements gained from diversified

sources. (Harlick, 2015) It presents obtaining information as an

interesting venture; it inspires setting up internal rules instead of

following external ones. (Komenczi, 2009:2) A system successfully

serving the education of generation Z prefers project-based development

gained in free time frame. Instead of conformism it builds on

individual creativity, self-criticism and innovation. Students do not

meet up the requirements of teachers, but standards set up based on

different disciplinary standpoints (Anderson, 2011: 126), while the

work is carried out in smaller groups of heterogeneous composition, in

what the older generation is adult, and successfully motivates the

creation of the ability of lifelong learning.

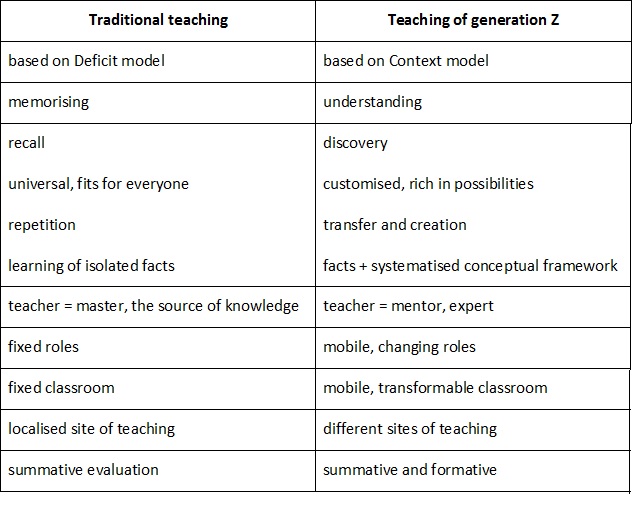

Response to the question how such learning environment can be

established among the traditional schools is given by the so-called

emphasis-transfer model, which says that the desired learning

environment of information society can also be approached by

contrapositioning the characteristics of traditional environment

organisation, built primarily on instructions and one-direction

knowledge transfer, and the characteristics of the progressive, rather

constructivist one. Naturally, the statements in the below table are

not contrapositions excluding, but supplementing each other, which

serve to show in what direction should the current education system

move on in order to suitably serve the demands of generation Z.

(Komenczi, 2009:2)

Table 3 – The Differences between

Traditional Learning Environment and Progressive Learning Environment

Implementation of the methodology

summarised in the above table requires application of the technology

what is able to fulfil the device requirement of progressive learning

environment. Within this scope several solutions, customised for the

characteristics of generation Z, might get role from the interactive

boards through the so-called Learning Management (LMS) technologies,

through e-Learning framework systems and multi-user educational games

to smart phones (MLearning) (Brown, 2005) In education it is necessary

to provide space in growing proportion for those different web 2.0

applications, which are used by the students already in their free

time: besides multimedia, information and video sharing sites (YouTube,

Flickr, Google), social sites (Facebook, Linkedin, MySpace), virtual

worlds (River City, Atlantis, Whyville, etc.) and multi-player games

(Rich Man Game, ChangeMaster, Quest Ardene, etc.) are vital to be built

in the course of education in the 2010s. Furthermore Olympiou and

Zacharia pointed out that experimenting with blended combinations of

Physical Manipulatives (PM) and Virtual Manipulatives can be able to

enhance students’ conceptual understanding in the domain of various

scientific topics more than the use PM and VM alone. (Olympiou &

Zacharia, 2011:38)

If traditional teaching and curriculum is combined with innovative

teaching methods, multimedia elements and modern devices that

facilitate an interactive, flexible learning process involving several

sensual organs. (Molnár, 2007) Because of experimental lust, target and

success-oriented approach and strong network dependence it is important

that the institutions shall provide rooms suitable for work in

ethnically diversified small teams. Since youngsters are pragmatic and

inductive information processors, it is worth to provide them media

promoting cooperation, where they can gather knowledge from several

sources, by the use of integrated devices and in the course of

training-like situations. This, besides charming and challenging

materials needs analysing, and presentation applications, divided

screens, databases, programs necessary for editing multimedia and

access to online helper. (Brown, 2005) Thus adaption of the everyday

education activity to the technical environment would make the

curriculum not only more interesting and easier to follow up, but it

would enhance the learning lust and success of the students.

Naturally, besides transformation of the environment pedagogues expert

in info-communication technologies are also vital. Since the knowledge,

attitudes and skills of the net-generation is expressly limited by the

current educational system, paradigmatic alterations would be necessary

also in the preparation of the pedagogues.

[12]; Collaborative,

problem- and project-based education (Pease & Kuhn, 2010) requires

new type of teachers, special facilitators, who – in excess of their

disciplinary knowledge – possess high level knowledge on

information-technological knowledge and competency. (Roberts, 2005)

Teachers of 2010s must be able to actively involve and apply in

teaching those modern technologies, what are used by their primary

target group. If implementation of this fails the members of the young

generation shall lose interest in education, and will use the internet

for other activities, what they consider as interesting and what brings

joy to them. (Duga, 2013)

Summary: Are these sociological

problems or pedagogical possibilities?

In this article I attempted to give detailed presentation of those

changes what has taken place in the socialisation, world view, skills

and media usage of generation Z due to the development of

info-communication technologies. I was reasoning on behalf of that this

multi-dimensional transformation raises not only generation gaps,

sociological and pedagogical problems, but at the same time it creates

possibility for an educational reform leading to transfer of knowledge,

what is up-to-date, customised to the demands of the youngest ones and

promotes integration into labour market effectively.

Consequently, renewal of education is

only an umpteenth step: technology and service provision planning

should be preceded by an action- and intervention-focused society and

child-image, what has definite and normative ideas originating from

internal initiations about how and in what direction it wants to form

the conditions defining science society. (Z. Karvalics, 2013) In order

to achieve this it is inevitable to paradigmatically change the

approach related to generational discrepancies. According to Jukes we

are unable to understand and evaluate those stages of development,

which the digital natives took during developing their skills. Instead

of this we are lamenting over what skills they do not possess. Since

digital language is not our native language, and since we appear in

their world as digital immigrants, we unconsciously misesteem those

children who practice different forms of action than we do; and this

negligence prevents exploitation of the social potential hidden in

them. (Jukes & Dosaj, 2006)

However this study did not declared to deal this issue, yet it is

important to emphasize that information environment aware management

must firstly appear on the level of disciplinary policy, what shall -

as a complex “pre-reforming” strategic package - create future

possibility for the members of the generation growing up through

digital culture to become a full value member of the community also in

their person. Consequently a science communication paradigm shift

discussed in this article is a very complex process taking long in time

and space: thus there will be schools shoving information society

features in several elements, while in other countries and schools

industrial era will still rule. (B. Tier, 2014) The education system is

set up from several factors; accordingly considering reform we can only

talk about slow distortion of ratios, what is preceded by experiments.

However, if a kind of structural and methodological change can be

successfully implemented in education, the members of generation Z will

spent a part of their free time after school also for self-development,

moreover they will do that in way unnoticeable for them, since they

will engage themselves in exactly the same activities what they do in

their everyday obligatory activities.

[13]

One of the key factors of a possible structural and methodological

change is to reconsider the current accountability policy. According to

Anderson the actual one does not meet the aims and needs of a reform,

so he strongly suggest that education leaders and policy makers “need

to evaluate whether or not accountability policies inspire teachers and

students in science, foster innovation, and increase teachers’ ability

to use research-based practise.” (Anderson, 2011:125) He points out

that “accountability testing in science should place more emphasis on

skills and scientific reasoning found in instructional methods such as

inquiry and active learning. Furthermore accountability systems should

use “multiple measures of students’ ability, connecting to creativity ,

and students enjoyment of learning.” (Anderson, 2011:125)

Thus, concentrating on media consumption, characteristics and world

view features of the generation, I am also urging the setting-up of a

science communication methodology, which, based on the Context model of

Public Understanding of Science, facilitates cooperation between

digital immigrants and digital natives, what is collaborative,

project-based, customised, adapting to changes of the world and rich in

possibilities and interactions. This requires the establishment of

progressive learning environment, and that pedagogues shall review

their function and preparedness so that they can participate in

information transfer rather as experts or mentors than along fixed

pre-defined roles.

The most significant philosopher of China, Confucius (551-479B.C.) says

“if I hear it, I forget it; if I see it, I remember it; if I do it

myself, I understand it.” Accordingly, the demands and interest

of generation Z can be met only by an educational strategy built on

flexibility in time and space (McWilliam, 2015), teamwork and the

existing knowledge of the age-class, this way it would be worth if

curriculum developers and science managers placed competency-based and

pragmatic approaches in the forefront instead of traditional,

content-based, theoretical approaches. A precondition to this is that

the state shall assure access for each and every member of generation Z

to the necessary information technology, what is a definitive step to

bridge the social gap dividing the younger generation; to provide equal

chances for the richer and less privileged layers.

Although the section did not analyse

the limits of cognitive skills of generation Z, mapping them is also

vital in respect of social problems and conflicts between age-classes.

Recently several – and at first sight frightening – socio-psychological

results were derived from research, which prove the harmful impact of

technology in the human relationships and cognitive skills of the ones

born at the end of 1990s. (Pintér, 2013b) Therefore there will be

plenty of professional challenges in the future, but we cannot delay

too much with modernisation of the science communication process, since

within a couple of years the knowledge of our children – as they will

become future employees, decision-makers, voters, and teachers of the

forthcoming generation Alpha – will be the main drive of the

development of the society.

Bibliography

- Anderson, K. J. B. (2011). Science Education and

Test-BasedAccountability: Reviewing TheirRelationship and

ExploringImplications for Future Policy. Science Education, 96(1),

104-129

- Asheim, G. B. & Tungodden B. (2004). Resolving distributional

conflicts between generations, Economic Theory, 24(1), 221-230.

- B. Tier, Noémi (2014). Tanulás az információs társadalomban

[Learning in the Information Society] In. B.Tier N. & Szegedi E.

(Eds.), Alma a fán – A tanulás jövője. [Apple on the Tree: the Future

of Learning] (pp. 16-23) Tempus Közalapítvány, Budapest, Hungary.

Available from:

https://issuu.com/tka_konyvtar/docs/alma_a_fan_3_web_issuexs [Accessed:

17th May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Bauer, M. W. (2009). The evolution of public understanding of

science - discourse and comparative evidence. Science, technology and

society. 14(2), 221-240.

- Bell, D. (1974). The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. New York:

Harper Colophon Books.

- Beniger, J. R. (1986). The Control Revolution: Technological and

Economic Origins of the Information Society. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

University Press.

- Bessenyei, I. (2007): Tanulás és tanítás az információs

társadalomban: az E-learning 2.0 és a konnektivizmus. [Learning and

Teaching in the Information Society: E-Learning 2.0 and Connectivism]

Budapest. [Online] Available from:

http://www.ittk.hu/netis/doc/ISCB_hun/12_Bessenyei_eOktatas.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Biggs, S. (2007). Thinking about generations: Conceptual

positions and policy implications. Journal of Social Issues. 63(1),

695–711.

- Billing, D. (2004). Teaching Learners From Varied Generations.

The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 35(4), 104-105.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge

University Press.

- Brown, Malcolm (2005). Learning Spaces. In D. G. : Oblinger @ J.

L. Oblinger (Eds.), Educating the Net Generation. EDUCAUSE.

12.1.-12.22. [Online] Available from:

http://www.educause.edu/research-and-publications/books/educating-net-generation/learning-spaces

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Castells, M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. The

Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. 1. Cambridge, MA;

Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (1997). The Power of Identity. The Information Age:

Economy, Society and Culture. 2. Cambridge, MA; Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (1998). End of Millennium. The Information Age:

Economy, Society and Culture. 3. Cambridge, MA; Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Castells, M. (2006). The Network Society: from Knowledge to

Policy. In: M. Castells & G. Cardoso (Eds.): The Network Society:

From Knowledge to Policy (pp. 3-22) The Johns Hopkins University Press,

Center for Transatlantic Research Relations, Washington, DC

- Cisco – Intel – Microsoft (2009). Transforming Education:

Assessment and Teaching 21st Century Skills. [Online] Available from:

http://atc21s.org [Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Combi, C. (2015). Generation Z: Their Voices, Their Lives.

London: Hutchinson.

- Csepeli, Gy. (2007). A jövőbe veszett generációk. [Generations

Lost in the Future] In M. Palcsó (Ed.) Mesterkurzus. [Master Course]

Budapest: Saxum. (pp. 87–105). (in Hungarian)

- Demers, D. (2005). Dictionary of Mass Communication and Media

Research: a guide for students, scholars and professionals, Marquette

Books, 143.

- Duga, Zs. (2013): Tudomány és a fiatalok kapcsolata [The

Connection between Youngsters and Science] Pécs

(TÁMOP-4.2.3-12/1/KONV-2012-0016) Tudománykommunikáció a Z

generációnak) [Science Communications to Generation Z] Available from:

http://www.zgeneracio.hu/getDocument/331 [Accessed: 17th May 2016] (in

Hungarian)

- Dunkels, E. (2007). Bridging the Distance – Children’s Strategies

on the Internet. Doktorsavhandlingar i pedagogiskt arbete, Umeå

Universitet. [Online] Available from:

http://www.kulturer.net/documents/bridging_hela.pdf [Accessed: 17th May

2016]

- Dupont,

S. (2015). Move Over Millennials, Here Comes Generation

Z: Understanding the 'New Realists' Who Are Building the Future. Public

Relations Tactics. Public Relations Society of America. [Online]

Available from:

https://www.prsa.org/Intelligence/Tactics/Articles/view/11057/1110/Move_Over_Millennials_Here_Comes_Generation_Z_Unde#.VzrhSfmLTIU

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2002). The generational conflict

reconsidered. Journal of European Social Policy, 12(1). 5-21.

- EU Kids Online II (2011): A magyarországi kutatás eredményei.

[Results of the Hungarian Research] Nemzeti Média és Hírközlési

Hatóság, Budapest (in Hungarian)

- Fehér, P. & Hornyák J. (2010). Netgeneráció 2010: Egy

felmérés tanulságai. [Netgeneration 2010: Consequences of a Survey]

Budapest. [Online] Available from

http://hu.scribd.com/doc/48558319/Feher-Peter-Hornyak-Zsolt-Net-Generation-2010

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Gass, S. & Selinker, L.(2008). Second Language Acquisition:

An Introductory Course. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gergátz, I. (2009). ICT az 50+ generáció életében. [The Role of

ICT in the Life of 50+ Generation], Ph.D. Thesis, Pécsi Tudományegyetem

Közgazdaságtudományi Kar Gazdálkodástani Doktori Iskola, Pécs.

Available fom:

http://ktk.pte.hu/sites/default/files/mellekletek/2014/07/Gergatz_Ildiko_disszertacio.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Glass, A.. (2007). Understanding generational differences for

competitive success. Industrial and Commercial Training, 39(2), 98-103.

- Gregory, J. & Steve M. (1998). Science in Public:

Communication, Culture, and Credibility. New York: Plenum Trade.

11-17., 88-98.

- Gregory, J. & Steve Miller (2006). Kereszttűzben? A

nyilvánosság szerepe a tudományháborúban. [Caught in the crossfire, the

public's role in the science wars] Replika, 54-55(1), 195-205.

- Guld, Á. & Maksa Gy. (2013): Fiatalok kommunikációjának és

médiahasználatának vizsgálata, [Investigations about the Communication

and Media Use of Youngsters] Pécs (TÁMOP-4.2.3-12/1/KONV-2012-0016)

Tudománykommunikáció a Z generációnak [Science Communications to

Generation Z] Available from: http://www.zgeneracio.hu/getDocument/501

[Accessed: 17th May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Hall, J. M. (2007). A History of the Archaic Greek World.

Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hamza, K. M. & Wickman, P. (2013). Supporting Students’

Progression in Science: Continuity Between theParticular, the

Contingent, and theGeneral, 97(1), 113-138

- Harlick,

A. M. & Halleran, M. (2015). There Is No App for

That Adjusting University Education to Engage and Motivate Generation

Z. Conference: New Perspectives in Science Education, Italy. [Online]

Available from:

http://www.researchgate.net/publication/273893292_There_Is_No_App_for_That__Adjusting_University_Education_to_Engage_and_Motivate_Generation_Z

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Hartyányi, M. (2010). A Net Generáció kihívása. Tanárok a hálón.

[Challenges of NetGeneration. Teachers on the Web] TeNeGEN. Budapest.

[Online] Available from:

http://www.tenegen.eu/sites/tenegen.eu/files/tenegen/books/R10_Tenegen_Book_HU_CD.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Hinrichs, R. (2000). A Vision for Life Long Learning – Year 2020.

Introduction by Bill Gates. Learning Science and Technology Microsoft

Research. Microsoft. [Online] Available from:

http://vision.cer.uz/Data/lib/readings/ff_social_development/SOC_Microsoft__A_Vision_for_Life_Long_Learning__2020_EN_2006.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Horovitz, B. (2012). After Gen X, Millennials, what should next

generation be? USA Today. [Online] Available from:

http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/advertising/story/2012-05-03/naming-the-next-generation/54737518/1

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Howard, J. A. (2000). Social Psychology of Identities, Annual

Review of Sociology, 26(1), 367-393.

- Howe, N. - Strauss, W. (1991). Generations: The History of

Americas Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow. 299–316.

- HVG (2014): Klasszikus módszerekkel nem lehet a Z-generációt

tanítani. [GenZ Can’t be Taught by Classical Methods] [Online]

Available from

http://hvg.hu/plazs/20140424_Klasszikus_modszerekkel_nem_lehet_a_Zgen

[Accessed: 17th May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Ipsos Media CT (2013). GenZ: The Limitless Generation – A Survey

of the 13-18 Year-Old Wikia Audience. [Online] Available from:

http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/generation-z-a-look-at-the-technology-and-media-habits-of-todays-teens-198958011.html

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Joshi, A. & Dencker, J. C. & Franz, G. & Martocchio,

J. J. (2010). Unpacking Generational Identities in Organizations.

Academy of Management Review,35(3), 392-414.

- Jukes, I. & Dosaj, A (2003). The differences between digital

native learners and digital immigrant teachers. The InfoSavvy Group.

[Online] Available from:

http://edorigami.wikispaces.com/Understanding+Digital+Children+-+Ian+Jukes

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Jukes, I. & Dosaj, A. (2006). Understanding Digital Children

(DKs) Teaching & Learning in the New Digital Landscape, The

InfoSavvy Group. [Online] Available from:

https://web.archive.org/web/20061018134943/http://ianjukes.com/infosavvy/education/handouts/ndl.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Karp, H. B. & Sirias, D. (2001). Generational Conflict A New

Paradigm for Teams of the 21st Century. Gestalt Review, 5(2), 71–87.

- Kolin, P. (2002). Idősek az információs társadalomban [Elders in

the Information Society], Evilág, Available from:

http://www.pointernet.pds.hu/ujsagok/evilag/2002/07/evilag-06.html

[Accessed: 17th May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Komenczi, B. (2009). Informatizált iskolai tanulási környezetek

modelljei. [Models of Computerized School Learning Environments]

Oktatáskutató és Fejlesztő Intézet, Budapest. [Online] Available from:

http://regi.ofi.hu/tudastar/iskola-informatika/komenczi-bertalan

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Kristiansen, R. (2011). Digital natives - Thinking map. [Online]

Available from:

http://roarkristiansensblogg.blogspot.hu/2011/03/digital-natives-mindmap.html

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Landon, J. (1980). Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom

Generation, New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan

- Lengyel, Gy. (2003). Az információs technológia terjedésének

társadalmi hatásairól. [The Social Effects of Sprading Information

Technology] In. Információs technológia és életminőség [Information

Technology and the Quality of Life] BKÁE Szociológia és Szociálpolitika

Tanszék, Budapest, pp. 5-10. Available from

http://unipub.lib.uni-corvinus.hu/526/1/ite1_bev.pdf [Accessed: 17th

May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Lewenstein, B. V. (2003). Models of public communication of

science and technology. [Online] Available from:

http://disciplinas.stoa.usp.br/pluginfile.php/43775/mod_resource/content/1/Texto/Lewenstein%202003.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Mannheim, K. (1952). The Problem of Generations. In Kecskemeti,

Paul. Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge: Collected Works, Vol. 5.

New York: Routledge. 276-322.

- Markert, J. (2004). Demographics of Age: Generational and Cohort

Confusion. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising. 26,

15.

- Masnick, G. (2013). Defining the Generations. Harvard Joint

Center for Housing Studies. Available from:

http://housingperspectives.blogspot.hu/2012/11/defining-generations.html

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- McCrindle, M. (2010). The ABC of XYZ. Australia: University of

New South Wales.

- McWilliam, Er. (2015). Teaching Gen Z. EricaMcWilliam.com.

[Online] Available from:

http://www.ericamcwilliam.com.au/teaching-gen-z/ [Accessed: 17th May

2016]

- Menco Platform (2013). Top 10 Educational Trends by Menco

platform on Flickr. [Online] Available from:

http://pinterest.com/pin/240520436321607462/ [Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Miller, J. D. (2012). The Generation X Report: Active, Balanced,

and Happy: These young Americans are not bowling alone. University of

Michigan, Longitudinal Study of American Youth, funded by the National

Science Foundation.

- Molnár Gy. (2007). New ICT Tools in Education - Classroom of the

Future Project. In. D. Solesa (Ed.): The fourth international

conference on informatics,Moleducational technology and new media in

education. A. D. Novi Sad. pp.332-339. [Online] Available from:

http://www.staff.u-szeged.hu/~gymolnar/New_ICT_tools_in_Education_paper_pictures.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Molnár, Gy. (2008). The use of innovative tools in teacher

education: a case study. In: D. Solesa (Ed.): The fifth international

conference on informatics, educational technology and new media in

education. A. D. Novi Sad. pp. 44-49. Available from:

http://www.staff.u-szeged.hu/~gymolnar/sombor_2.pdf [Accessed: 17th May

2016]

- Nahalka, I. (2002). Hogyan alakul ki a tudás a gyerekekben?

Konstruktivizmus és pedagógia. [The Development of Knowledge in

Children: Constructivism and Pedagogy] Budapest, Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó.

(in Hungarian)

- Ng, E.S.W. & Lyons, S.T. & Schweitzer, L. (2010). New

generation, great expectations: A field study of the millennial

generation. Journal of Business Psychology, 25(1), 281-292.

- NOL (2014): A fiatalok gyors információkra vágynak, nem elmélyült

fejtegetésekre. [Youngsters want fast informations not deep

considerations] [Online] Available from:

http://nol.hu/belfold/a-fiatalok-gyors-informaciokra-vagynak-nem-elmelyult-fejtegetesekre-1458275

[Accessed: 17th May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Nyíri, K. (1999). Identitáskérdések az elektronikus hálózottság

korában. [Questions about Identities in the Era of Electric Networks]

Magyar Pszichológiai Szemle, 56 (1), 19-21. (in Hungarian)

- Nyíri, K. (2004). Információs társadalom és nemzeti kultúra. .

[Information Society and National Culture], Információs Társadalom,

5(1), 7- 16. (in Hungarian)

- Oblinger,

D. G. & Oblinger, J. L. (2005). Is It Age or IT:

First Steps Toward Understanding Ethe Net Generation. In: Oblinger, D.

G. & Oblinger, J. L. (Eds.): Educating the Net Generation.

EDUCAUSE. 2.1-2.20. [Online] Available from:

http://www.educause.edu/research-and-publications/books/educating-net-generation/it-age-or-it-first-steps-toward-understanding-net-generation

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Olympiou, G. & Zacharia, Z. C. (2011). Blending physical and

virtual manipulatives: An effort to improve students' conceptual

understanding through science laboratory experimentation. Science

Education, 96(1), 21-47.

- Owram, Doug (1997). Born at the Right Time, Toronto: Univ Of

Toronto Press.

- Palugyai, I. & Wormer, H. & Lehmkuhl, M. & Bán, L.

& Neumann, V. (2012). Tudományos újságírás. [Science Journalism]

Budapest: Tudományos Újságírók Klubja.

- Papert, S. (1996). The Connected Family. Longstreet Publishing,

Atlanta.

- Parry, E. & Urwin, P. (2011). Generational Differences in

Work Values: A Review of Theory and Evidence. International Journal of

Management Reviews, (13)1, 79–96.

- Pease, M. A. & Kuhn, D. (2010). Experimental analysis of the

effective components of problem-based learning, 95(1), 57-86.

- Pilcher, J. (1994). Mannheim's Sociology of Generations: An

undervalued legacy. British Journal of Sociology, 45(3), 481–495.

- Pintér, Dániel Gergő (2013a). A tudományos tartalmú

közlésfolyamat a globális médiatérben. [Science Communication in Global

Media] Tudományos Próbapálya Conference Book. PEME. pp. 23. ISBN

979-963-88433-8-8 Available from:

http://www.peme.hu/userfiles/Interdiszciplin%C3%A1lis%20%C3%A9s%20tudom%C3%A1nyfiloz%C3%B3fia.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016] (in Hungarian)

- Pintér, Dániel Gergő (2015). Bruno Latour Cselekvő Hálózat

Elméletének alkalmazása a modern tudománykommunikációban [The

Application of Bruno Latour’s ANT int he field of Science

Communication] In. III. Interdiszciplináris Doktorandusz Konferencia

2014. Conference Book ISBN 978-963-642-741-2. pp. 455-465o. [Online]

Available from: http://phdpecs.hu/idk2014/index.html [Accessed:

17th May 2016]

- Pintér,Dániel Gergő (2013b). Semmivel sem törődik a Z-generáció.

[GenZ doesn’t Care abut Anything] Média 2.0 Blog. [Online] Available

from: http://media20.blog.hu/2013/04/18/a_boseg_zavara_121 [Accessed:

17th May 2016]

- Prensky, M. (2001): Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the

Horizon, 9(5), 1–6.

- Roberts,

G. R. (2005). Technology and Learning Expectations of

the Net Generation. In Oblinger, Diana. G. and Oblinger, James. L.

(Eds.). Educating the Net Generation. EDUCAUSE. 3.13.7. [Online]

Available from:

http://www.educause.edu/research-and-publications/books/educating-net-generation/technology-and-learning-expectations-net-generation

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Rückriem, G. (2009). Digital technology and mediation: A

challenge to activity theory. In A. Sannino & H. Daniels & K.

Gutierrez (Eds.), Learning and expanding with activity theory. pp.

30-38. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smetana, L. K. & Wenner, J. & Settlage, J. & McCoach,

D. B. (2016). Clarifying and Capturing “Trust” in Relation to Science

Education: Dimensions of Trustworthiness within Schools and

Associations with Equitable Student Achievement. Science Education,

100(1), 78-95.

- Sterbenz, C. (2015). Here's who comes after Generation Z - and

they're going to change the world forever. Business Insider. . [Online]

Available from:

http://www.businessinsider.com/generation-alpha-2014-7-2 [Accessed:

17th May 2016]

- Strauss, W. & Howe, N. (2000). Millennials Rising: The Next

Great Generation. Cartoons by R.J. Matson. New York, NY: Vintage

Original. 370.

- Tari, A. (2011). Z generáció [Generation Z] Budapest: Tericum

Kiadó Kft. (in Hungarian)

- Trunk, P. (2009). What Generation Z will be Like at Work.

[Online] Available from:

http://blog.penelopetrunk.com/2009/07/27/what-work-will-be-like-for-generation-z/

- Turner, A. (2015). Generation Z: Technology and Social Interest.

Journal of Individual Psychology. 71(2), 103-113.

- Ujhelyi, A. (2013). Digitális nemzedék – szociálpszichológiai

szempontból [Digital Generation from the Perspective of Social

Psychology] Digitális Nemzedék 2013 Conference Book, Budapest, 9-14.

(in Hungarian)

- Urick, M. J. (2012). Exploring Generational Identity: A

Multiparadigm Approach. Journal of Business Diversity, 12(3), 103-115.

- Vikat, A. & Spéder, Zs. & Beets, G. & Billari, F.

& Bühler, C. & Desesquelles, A. & Fokkema, T. & Hoem,

J. M. & MacDonald, A. & Neyer, G. & Pailhé, A. &

Pinnelli, A. & Solaz, A. (2007): Generations and Gender Survey

(GGS): Towards a Better Understanding of Relationships and Processes in

the Life Course. Demographic Research, 17(14), 389-440. Webster, F.

(1997). Theories of the Information Society. London: Routledge.

Available from:

http://cryptome.org/2013/01/aaron-swartz/Information-Society-Theories.pdf

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- West, A. & Pen, I. & Griffin, A. S. (2002).

Cooperation and Competition Between Relatives. Science, 296(5565),

72-75.

- Williams, A. (2015). Meet Alpha: The Next ‘Next Generation. New

York Times. [Online] Available from:

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/19/fashion/meet-alpha-the-next-next-generation.html?_r=0

[Accessed: 17th May 2016]

- Yelkikalan, N. & Ayhun, S. E. (2013). Examination of the

Conflicts Between X and Y Generations: Research for Academicians.

European Scientific Journal, 9(19), 19-33.

- Z. Karvalics, L. (2013). From Scientific Literacy to Lifelong

Research: A Social Innovation Approach. Worldwide Commonalities and

Challenges in Information Literacy Research and Practice, 397(1),

126-133

- Z. Karvalics, L. (2013). Mangalány mondja: közeledik a „digitális

beavatottak” ideje. [Manga Girl says: the "Digital Initiates' Time

Approaching] Conference Book: Digitális nemzedék 2013 Konferencia,

Budapest, 19-23. (in Hungarian)

- Z. Karvalics, L. (2014). Digitális kultúra és pedagógia: a

történeti metszéspontoktól az információs írástudások új generációjáig

[Digital Culture and Pedagogy] In. Polgári nevelés – Digitális oktatás.

Nyelv és módszer, Magyar nyelvstratégiai Intézet, 68-84. (in Hungarian)

- Zipernovzky, H. (2008). Felesleges időtöltés? [Useless Pasttime?]

Tanszertár, Budapest. [Online] Available from:

http://www.tanszertar.hu/eken/2008_02/zh_0802.htm [Accessed: 17th May

2016] (in Hungarian)

[1] This work was realized in the frames of OTKA

K-109456 “Integrated reasoning”

[2] During the past decades several researchers

analysed the generation conflicts and the challenges related to

coexistence of the older and younger generations (Esping - Andersen,

2002), its theoretical basis is defined on one hand by the classical

sociological thesis of Mannheim describing the generations as social

phenomena (Mannheim, 1952), and on the other hand by the definition of

individual habitude given by Bourdieu (Bourdieu, 1977). On this field

changes to the attitude is also measured by quantitative sociological

methods.(Andres et al., 2007), but the gap created the deviating

characteristics of generation X and Y (Yelkilalan & Ayhun, 2013),

the distribution problem (Asheim & Tungodden, 2004), challenges

represented by teaching students of different age (Billing,

2004), identity and values of diversified employees (Joshi et al.,

2010; Parry & Urwin, 2011) and the successful economic cooperation

of heterogeneous teams (Karp & Sirias, 2001; Glass, 2007) are also

popular topics.

[3] The field of PUS is in seek of answer to the

question how the population is related to the scientific product, what

image media communicates about science, how and on what channels, with

the help of what devices the relation between the non-professional

publicity and the science community is created. (Bauer, 2009) The

definition includes either the “normative and practical definitions

related to social understanding of science, or the main principles of

this area of science, or the social and educational commotion, which

rose after bringing up the problem; at the same time, the term is a

position profile, and area of research and practise for academics and

communicators.” (Pintér, 2013a:23)

[4] Closely related concepts are the post-industrial

society (Bell, 1974), post-fordism, post-modern society, knowledge

society, telematic society, information revolution, liquid modernity,

and network society. (Castells, 1996; 1997; 1998)

[5] Naturally the analysis of the next, so called

Generation Alpha or Generation Glass also raises several questions from

the aspect of terminology and sociology as well; this means a more and

more definitive focus of research for the sociologists. (McCrindle,

2010; Williams, 2015; Sterbenz, 2015; etc.)

[6] According to the basic principle of

socio-linguistics any language knowledge, which we obtain otherwise

than our native language, i.e. during our life, is stored at other

parts of our brain, and can be recalled in other – sometimes less

successful – ways. (Gass & Selinker, 2008)

[7] Non-traditional scientific sites provide the

experience of active observation and build also on the technical

skills, practical common sense, attention sharing and troubleshooting

skills of those born at the end of 1990s. Until meeting-up of the

pedagogical work going on in schools, the potential hidden in

environmental, informal education provided out of school lessons is

able to compensate – even if only partially and temporarily – this

generation. While the quantity of marketable knowledge obtained in

normal education is decreasing due to the often outdated methods, the

other channels used by the students provide them growing knowledge.

[8] Lewenstein uses the Rational Choice Theory for

this process, what focuses on the problem that from the uncountable

amount of knowledge which are the ones average people should inevitably

know so that they can positively influence the quality of their life in

a world interwoven with science. (Lewenstein, 2003)

[9] According to the basic theory of pedagogical

constructivism students learn that knowledge easier in what they are

directly involved, what is tangible for them, with what they meet in

living situation. (Nahalka, 2002)

[10] The Lay Expertise Model of science communication

is built on this idea; it supposes that the existing practical

knowledge is at least of the same importance as the theoretical

scientific knowledge. (Lewenstein, 2003) According to the scheme there

are experts also in excess of scientists and teachers; e.g. on the

field of info-communication the members of generation Z can rather be

considered experts than the pedagogues belonging to generation X or Y.

[11] This process is described in more details in

Public Engagement of Science model). (Lewenstein, 2003)

[12] In 2013 MENCO Platform carried out a research by

involvement of 100 Western European and American pedagogues, and it

resulted in that also the pedagogues are open to modernisation of

teaching, a significant number of them is interested in application of

online devices for teaching purposes. (Menco Platform, 2013)

[13] Formation of educational models is also

inevitable because the first global digital generation will enter the

labour market in a couple of years. Although in the article I did not

discuss the members of generation Z as employees, decisions on

modernisation of school lessons would be worth to think over by the

methodology developers also in respect of that the presence of the ones

born at the end of 1990s will obviously influence life at workplaces as

well. Since this age-class becoming adult, will cause changes not only

in the company systems, it will be not enough to be prepared to accept

the future “dotcom” adults only on behalf of the organisations, but

also the pedagogues should align the content of the curriculum, the

requirements and forms of call for accounting to the expectations of

the labour market.